Cultural Commentary: Arts Institutions, Unions, and the Pandemic

By Steve Provizer

It behooves audiences to be aware of how workers in the arts organizations they frequent are treated and whether management is operating in good faith.

An aerial still of the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s 2010 production of Othello on the Boston Common. Photo: Ryan Maxwell.

No one doubts the serious financial blow arts organizations have been suffering over the past year. According to the Massachusetts Cultural Council it’s something in the neighborhood of $588 million. With little income and minimal government support, even large institutions find themselves on shaky ground, while small theater and music venues are increasingly falling by the wayside. At the same time, the livelihood of thousands of arts workers is at stake, as is their health insurance, which many have lost because they have not worked enough hours to qualify. An equitable balance needs to be struck between the continued existence of these institutions and the survival of the people who make them work.

If artists, crafts people, and other workers at these organizations have any power to call for equity, it’s because of the strength of associated labor unions and guilds. Negotiations between union and management have never been easy or simple — even before the pandemic, demands for concessions led to bitter strikes by orchestra musicians in Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. But, in some cases, the pandemic has pushed these conversations to near breaking point. In this feature, I will look at the evolving relationship between unions and arts organizations at large institutions such as The Met, the Kennedy center in Washington, D.C., and the New York Philharmonic. Then, I’ll look at the situation in Boston.

In terms of outright turmoil, there’s New York’s Metropolitan Opera House (I’ll refer to it as The Met). The union insists that Met management has been using the crisis of the pandemic as an excuse to undermine organized labor. The Met employs about 2,500 union workers, 300 of whom are union stagehands. Labor costs make up two-thirds of its $300 million annual budget. Last spring, about 1,000 employees of The Met, including stagehands, musicians and members of the chorus were furloughed without pay by The Met, in the person of General Manager Peter Gelb. International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) Local One had offered to take a pay cut, but Gelb wasn’t satisfied. In December, Gelb announced he was “locking out” stage technicians and shop crew members such as carpenters and electricians who build sets at The Met and who are represented by IATSE, cutting off their wages and stopping the production of sets at Met facilities for the 2021 opera season. He is offering the stagehands, whose contract expired last July 31, pay of up to $1,500 a week, but only if they agree to a five-year contract that cuts their pay by 30 percent and still leaves it 15 percent below current levels — even after The Met box office completely recovers.

The management of MET strategy is crystal clear. Gelb told WABC-TV News: “With a lockout, it enables us to consider the possibilities of other options. There are other construction shops in this country and around the world that are not union.” The union has alerted U.S. government officials to The Met’s rumored plans to outsource set design work to shops in Russia. The union is launching a lobbying effort in Washington, D.C., Albany, and New York City that will ask lawmakers to exclude The Met or any other employer in the performing arts from stimulus or arts funds if they have locked out their workers.

The Met is also seeking massive cuts with other unions, including Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), and the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), which represents the chorus. So far, the AFM officials have rejected these proposals. The AMA, AGMA, and Coalition of Broadway Unions and Guilds, a union representing singers, dancers and stage directors have thrown their support behind the IATSE action.

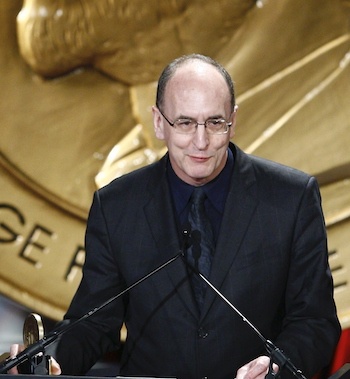

The MET General Manager Peter Gelb. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Gelb was paid over $2.1 million in combined pay and benefits in 2020. In response, he says he has suspended taking compensation, but the union believes his loss in pay will likely be made up later through deferred compensation or special bonuses. The Board of Directors and leading patrons of The Met is composed of multimillionaires and prominent members of billionaire families who have seen their stock portfolios reach record heights in the past year, Union members long ago stopped receiving their pay.

At the New York Philharmonic, musicians have agreed to extend a 25 percent cut in pay that began last May. This is a deal that will no doubt be weaponized to drive down salaries at other orchestras across the country. The new agreement says these cuts will continue until August 2023. They will gradually increase in two steps until September 2024, but the result is discouraging — the end of the contract will amount to less then the present base salary.

In Washington, D.C., the Kennedy Center has collective bargaining agreements with 15 unions and is at various stages of negotiations with all of them. The Washington National Opera (WNO), an arts center affiliate, agreed to extend its current contract with the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA) for a year. The stagehands’ Local 22 said they extended the same offer and that it was refused. In September, the arts center reached a new deal with National Symphony Orchestra musicians and, in late October, the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra agreed to 25 percent cuts in its contracts with the center and the WNO.

In Boston, the level of engagement and depth of cooperation between arts organizations and the relevant unions falls along a spectrum.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) has reached an accord with musicians (via the AFM). They will have an average 37% reduction in salary with (undisclosed) increases as revenue increases. With the cooperation of its musicians, the BSO has established a Resident Fellowship Program: “…for young musicians of color to study with BSO musicians and perform with the BSO and Boston Pops in their Symphony Hall seasons in Boston, as well as participate as a Fellow in the Tanglewood Music Center.” There are other union workers at the Symphony Hall, of course, but information has been difficult to obtain. It appears that the negotiations between the BSO and the musicians were collaborative, clarifying what can be expected from both sides in terms of on-line performances, collaborations, and educational outreach.

Bradley Vernatter, COO of the Boston Lyric Opera (BLO), is open to talking about the adaptations the organization is making to the pandemic. They are working with the 3 unions involved in their operation: American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), IATSE, and The American Federation of Musicians (AFM). In an average year — not like last year –between 350-400 union members are employed to work on BLO productions. Last winter, the opera troupe had prepared a production of Norma that COVID forced to close the day before it was to open. It was arranged that all the company’s actors, musicians, and technical staff be paid the full amount for which they had been contracted.

For its next scheduled productions, the BLO created pre recorded film versions (Fall of the House of Usher and Desert Inn) that could not be presented live. They plan to have digital technology as an option for their upcoming season — it depends on whether or not the pandemic allows for in-person performances. Adapting stage operations to digital platforms is a complicated business, says Vernatter; it took detailed conversations with unions to make this kind of transformation happen. Of course, this kind of strategic cooperation became much more feasible because some of the BLO revenue shortfall has been picked up by government grants and by the organization’s core group of contributors. Medium sized and smaller venues/organizations do not have this economic flexibility.

The labor situation smaller local venues are grappling with, explains Kate Snodgrass, Artistic Director of the Boston Playwrights Theatre, has its own challenges. For example, the BPT deals with a similar number of unions as the larger troupes, but the numbers are smaller: Actors’ Equity Association (6-10 or more each year), Society of Directors and Choreographers (2-5 each year), Dramatist Guild of America (3-5 playwrights each year) and IATSE (3-6 each year). BPT also received permission from Screen Actors Guild (SAG) to film a project — which was then cancelled because of Covid — and got permission from SAG/AEA to perform the Boston Theater Marathon online/Zoom for charity.

William and Roderick carrying a coffin in the Boston Lyric Opera production of Fall of the House of Usher. Photo: BLO.

Catherine Carr Kelly, Executive Director of the Central Square Theatre explains that the company is a member of New England Area Theatres (NEAT). She is the Co-Vice President of NEAT; Matt Chapuran is the the other Co-Vice President. Kelly reports that CST also works with USA, SAG/AFTRA, and SDC; it typically uses 20-25 union actors and stage managers in a season. “We are required,” says Kelly, “to hire over 60% Union Actors per production and USA and SDC are more infrequent — only a few contracts per season (2-6). The theater has negotiated streaming contracts, agreements with Theatre Authority (a nonprofit managed by Actors’ Equity), and was the third theater in the nation to negotiate an AEA contract to produce outdoor theater in August of 2020. That production was a collaboration with Front Porch Arts Collective, for whom CST is a fiscal sponsor.

Maurice Parent, Executive Director of The Front Porch Arts Collective, and himself a member of AEA, says they were able to get approval to use union actors through Central Square Theater’s agreement with NEAT. The negotiations were difficult at times: “Through it all I genuinely felt like they [the union] wanted actors to work.” He adds that he: “…recently worked with the union on a Theatre Authority contract for a zoom reading for Black History Month, and they were super helpful.”

Adam Sanders, Managing Director of the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company, says that in a typical season the company works with 10 or so members of Actors Equity and 4 – 6 members of United Scenic Artists. They have not yet negotiated new union contracts, and notes that CSC and labor share a common priority: the safety for staff, artists, and audiences. In working through strategies for the year ahead “…unions are a consideration, but not a driving factor.” Apart from issues of safety, Sanders cites the sustainability of CSC as uppermost, as well as maintaining the quality of the troupe’s performances. Fiscal shortfall from the pandemic, he says, has been made up primarily by federal support (PPP and EIDL). He adds: “Gains in some contributed revenue have compensated for some losses. We’ve also been successful in our digital programming, which has driven some donations.”

Chapuran, Executive Director of Boston’s Lyric Stage Company explains that, during the 2018-2019 season, the company used over 60 theatrical artists who were members of four theatrical unions. Since March, he says: “We’ve been working with…those unions, each of which has unique concerns.” As far as the company’s future fiscal condition, Chapuran is guarded: “Federal support and amazing philanthropy from our supporters has weathered us through this first 12 months of crisis,” but he warns that there are “huge unknowns looking forward.”

Central Square Theater presents Front Porch@Starlight: Dwayne P. Mitchell in Phoenix: Still I Rise. Photo: Nina Groom.

Last March, Mass MoCA, in North Adams, MA, laid off 120 of its 165 employees. Some were re-hired when the museum reopened in the summer. About 30 were not, and many of the returning staff members were given reduced hours. In November, employees voted to hold a union election. They decided that they would be represented by the Technical, Office, and Professional Union Local 2110 UAW, the same union that represents workers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The Mass MoCA unit would represent close to 100 staff, both full-and part-timers, according to Local 2110′s president, Maida Rosenstein.

The bottom line is that this is a turbulent climate for labor negotiations. The projected income cannot be accurately calculated yet organizations must have sufficient resources to pay the bills — and their workers. In the case of The Met, at least one of the reasons for labor strife is obvious: the institution’s board of directors refuses to pick up a significant amount of the shortfall. So unions are being called upon to bear the brunt of the financial squeeze. In other cases, as with the New York Philharmonic and the BSO, negotiations appear to have been made in good faith, giving union members a share in shaping the future of the institution. The agreements have meant a cut in pay, but that ensures the survival of a live-able wage as well as the future stability of the organization.

Institutions are depending on their supporters, board members and, to some degree, the government to pick up the fiscal slack. But a number of mid- to large- sized Boston theaters have also shown admirable creativity and flexibility. They understand the need to shift resources and create web-based audio and video productions. They have undertaken discussions with unions to iron out the relevant financial and rights agreements. The fact that in Boston all sides, management and labor, seem to be on the same page in accepting COVID safety protocols has made for easier negotiations.

Unless an impasse results in a strike, labor negotiations in arts institutions seldom attain visibility in the greater media. So it’s understandable that audience members don’t pay much attention to the complicated sub-structure of support that makes performing arts productions possible. After the pandemic, that must change: the public needs to understand that, whether or not anything is happening on stage, there’s always a lot going on backstage. It behooves audiences to be aware of the working conditions in the organizations they frequent and whether management is approaching unions in good faith. The bottom line is that institutions can draw on the resources I’ve written about here, but workers don’t have the same rich range of options. Moving forward, arts lovers should monitor how well arts management and labor are collaborating. And consider upping their level of financial support so fiscal considerations don’t lead to pressured negotiations between management and unions. Perhaps audiences need to expand the range of pleasure they expect the performing arts to deliver — not only should they enjoy what they see, but they should also be given the satisfaction that comes from knowing that all involved are being fairly compensated and treated.

Note: I reached out to speak with representatives of unions, but was unable to get a response by the release date of this story. I will provide an update as more information comes in. I’d like to thank Jim Kaufman for helping me get in contact with many of the people cited in this article.

Addendum:

Union Action in Bethesda

The venue-labor issues that I’ve talked about above are continuing to play out.

The latest example involves the Music Center at Strathmore in North Bethesda, MD and its ticket sellers, members of the Treasurers and Ticket Sellers Union, IATSE Local 868. Strathmore is home to the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and holds scores of performances in the visual and the performing arts.

At an action planned for this Sunday, May 30, at 5 p.m., the union will protest last fall’s release of 19 employees from the venue’s ticketing office and current plans to replace them with KIS Kiosk. The union claims Strathmore will lease the machines at a price higher than what it currently pays its human ticket sellers.

Joining the demonstration, which precedes a concert by trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, will be a giant inflatable rat. Union ticket sellers plan informational protests throughout the summer concert season.

Artsfuse.org will be reporting on future arts-related union activity as it unfolds across the country.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Just a note of enthusiastic agreement with Steve’s statement that “perhaps audiences need to expand the range of pleasure they expect the performing arts to deliver — not only should they enjoy what they see, but they should also be given the satisfaction that comes from knowing that all involved are being fairly compensated and treated.”

The buzz word “community” has been very abused by arts institutions for many years. But perhaps, post-pandemic, we can have the formation of a true community: not the “know your value” kind of entrepreneurship hawked on Cable TV and by fat cat foundations, but knowing and respecting the value of others. At least in part by strengthening unions and guilds by taking an interest in their well-being in terms of payment and fair treatment. Can’t that be part of the pleasure we take from the arts?