Book Feature: Remembering Norman Mailer

By David Daniel

Over six decades Norman Mailer managed, by turns, to engage and enrage and stir the zeitgeist’s pot.

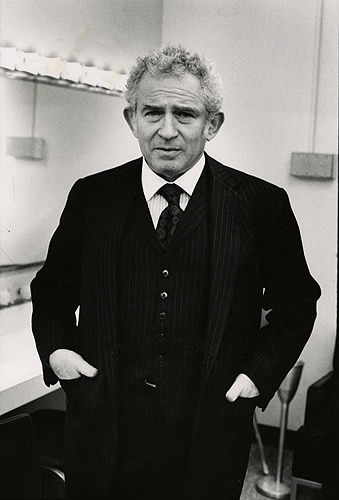

Norman Mailer — wanted to foment “a revolution in his time.” Photo: Wiki Commons.

Norman Mailer would have been 98 this month. He was born on January 31.

A while back, in one of my classes, I mentioned Mailer. Several students chorused: “Who’s Norman Mailer?” Which surprised me. This is a seminar at a state university. I thought for a moment, and interjected “He’s a thinking man’s Bukowski.” This got nods. Like a lot of their generation, the students know Bukowski. But not Mailer.

And yet, in a real sense, Mailer made Bukowski possible; or at least paved the way for Bukowski to write whatever he pleased, and Bukowski pleased plenty. But free, uncensored literary expression was not always an option for writers.

In the late 1940s, when Mailer was finishing his first novel, the epic naturalistic saga of World War II The Naked and the Dead, his editors emphatically forbade him to drop the f-bomb in its pages. Mailer argued that he was writing “about soldiers and combat and war and that the real obscenity isn’t language it’s…” and so on. But that plea fell on deaf ears: so, he coined the word “fug” to fill the gaps, and the guardians of decency allowed it to pass. (His euphemism for the “f” word later found use by the satirical underground band of the same name.)

Mailer tells of having decided at the end of his 16th year, during his first semester at Harvard, that he wanted to make the Big Time, to become, in his words, “a major writer.” He proclaimed Hemingway and, before him, Mark Twain, to be the writers who held what he deemed the “heavyweight” title. And indeed, making good on this overarching ambition (some would say attained by way of hyperbolic megalomania) drove a writing career that spanned six decades.

Beginning with short stories at college, then on to The Naked and the Dead, Barbary Shore and The Deer Park, Mailer dedicated himself to proselytizing for a philosophical/political vision that he called American existentialism. He was a professional dissenter, whose goal, as he declared in his 1959 nonfiction book Advertisements for Myself, had become nothing less than seeking to foment “a revolution in the consciousness” of his times.

Mailer found himself toiling in the same monochromatic world of ’50s America that Jack Kerouac lived in. However, while Kerouac’s path took him on the road, Mailer, a precocious son of New Jersey and Brooklyn, chose more or less to stay put in the belly of the beast, home to Madison Avenue and the corporate mass media, and duke it out there.

Of Kerouac, whom he met and liked, Mailer wrote: “His literary energy is enormous, and he had enough of a wild eye to go along with his instincts and become the first figure of a new generation. His love of language had an ecstatic flux. To judge his worth, it is better to forget about him as a novelist and instead see him as an action painter or a bard.” A pretty astute comment, still. I love Kerouac and regard him as a great artist but, frankly, I’ve never considered him much of a fictionist per se, nor, for that matter, Mailer, either.

Mailer did go on to grab some literary brass rings — the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize twice. He tells a humorous story about having mistakenly thought he was tapped for the Nobel one year; instead, it was French writer Andre Malraux, who was being considered, but he didn’t win. Mailer’s conventional novels weren’t what won the awards. The nonfiction/fictionalized books will be the ones that last, such as The Armies of the Night, his engrossing account of a 1967 antiwar march on the Pentagon, and 1979’s true crime yarn The Executioner’s Song, an impressively analytical tale of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore. These volumes were (like Kerouac’s books) narratives inspired by happenings in real life into which Mailer injected his perceptively iconic persona, energized by an expansive male ego. In this sense, both writers helped create what came to be called the “New Journalism.”

But let’s not quibble about labels. At his best Mailer was a smart and original wordsmith. Even when he was not at his best, obviously concerned to earn a paycheck to deal with his spiraling alimony payments (a serial wedding groom— he was married 6 times and had 9 children), Mailer wrote riveting, breath-catching, thought-provoking prose. Generally, Mailer managed, by turns, to engage and enrage and stir the zeitgeist’s pot.

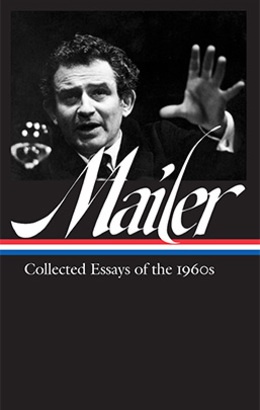

A good place to start reading Mailer: The Library of America’s volume of his ’60s essays.

His list of works is long: The White Negro; An American Dream; Miami and the Siege of Chicago; Of a Fire on the Moon; A Prisoner of Sex; Why Are We in Vietnam?. And then there are the psycho-biographies of cultural figures as diverse as Marilyn Monroe, Picasso, Lee Harvey Oswald — even Jesus. There’s his fun-ish crime novel set in Provincetown, Tough Guys Don’t Dance. And big, late career books that erred on the side of the bombastic, Ancient Evenings and Harlot’s Ghost. In his final novel, Castle in the Forest, he returned to something more closely resembling mainstream fiction, though not effectively.

Every bit as controversial as Mailer on the page was Mailer on the public stage, where he met his readers’ expectations: pugnacious, challenging, funny, larger than life (though physically diminutive), and frequently brilliant in his talk. Even when his ideas strayed far beyond plausibility — his ’70s proclamation, for instance, that good orgasms make good babies — he was still provocatively entertaining. (You can catch this side of Mailer in the 1979 documentary Town Bloody Hall, its recent release on the Criterion Collection reviewed by the Arts Fuse.)

Any writer needs a window from which to look upon the world, be it small (as is the case, necessarily, of most writers working today) or large (as was true of 19th-century giants like Tolstoy, Dickens, Melville). Of his mid-20th-century contemporaries, Mailer came closest to this latter category — or at least he struggled to measure up. So, Norman Mailer, 1923–2007—Rest in Peace. We shan’t see your like again anytime soon.

Back to Bukowski for a moment, and my students’ comment. I like Bukowski, too. He’s a true original; love him or hate him, when he was on his game, he can get you to feel something, to react.

Mailer, when he was good, he got you to feel and to think. And for a writer, that’s the Big Time, baby.

Arts Fuse review of the Selected Letters of Norman Mailer.

David Daniel is the author of more than a dozen books, including four entries in the prize-winning Alex Rasmussen mystery series. His most recent book is Inflections & Innuendos, a collection of flash fiction. He blogs regularly @Richardhowe.com.