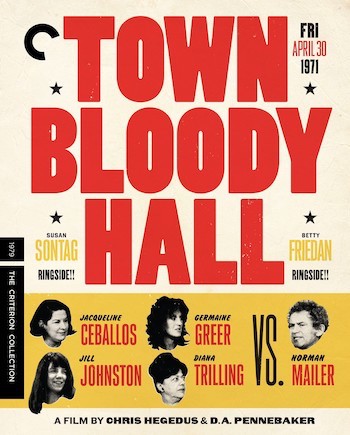

Film Review: “Town Bloody Hall” — Rip-Roaring Feminist Cross Fire

By Thomas Doherty

The 1979 documentary Town Bloody Hall is a time-tunnel passageway into what stand-up comedians used to call “women’s lib.” It is still liable to raise a gendered ruckus — and provide a rollicking good time.

Sometime in the late ’80s, at a repertory screening of Town Bloody Hall at the beloved and now temporarily shuttered Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, MA, I witnessed confirmation of the hypodermic needle theory of mass communication. Midway into Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s cinema verité chronicle of the rhetorical donnybrook billed as “A Dialogue on Women’s Liberation,” held at New York’s Town Hall on April 30, 1971, a fight broke out between a man and a woman in the audience — the Brattle audience, that is — first verbally, over one or the other’s too-loud commentary on the disputations in the film, then physically, when the argument escalated into a shoving match. The Cambridge police arrived and hauled off the guy, and the woman yelled victoriously, “The cops are taking that pig off to jail!” I can’t recall if the lights in the theater went up during the brouhaha, or the film continued playing as suitable background noise to what it had incited.

Whether in 1971, when the event was filmed, or 1979, when the long-gestating project premiered at the Whitney Museum of Art, or, dare I say today, when Town Bloody Hall is the object of a spiffy release by The Criterion Collection on Blu-ray, the time-tunnel passageway into what stand-up comedians used to call “women’s lib” is liable to raise a gendered ruckus — and provide a rollicking good time.

The ostensible catalyst for the fight card was a discussion of Norman Mailer’s recently published essay The Prisoner of Sex in Harper’s magazine, a characteristically self-caressing cri de phallus written in response to Kate Millet’s accusation in Sexual Politics (1970) that Mailer, like Henry Miller and D. H. Lawrence, was a “counter revolutionary sexual politician” with a Nazi outlook on women. Millet refused to participate in the colloquium, so a quartet of heavyweight feminists stepped up: Jacqueline Ceballos, Germaine Greer, Jill Johnston, and Diana Trilling. Happy to strut as cock of the walk, Mailer was the designated moderator, mansplainer, and patriarchal ogre. At the outset, he says even a man with his legendary vanity is not so egotistical as to think he can go mano a mano with four female contenders, but you just know he thinks it’s an even match.

The proceedings are conducted according to Robert’s — not the Marquess of Queensberry’s — Rules of Order: each panel member speaks at the podium for 10 minutes, Mailer responds, and then questions are solicited from an audience packed with a cadre of deeply Caucasian literary, professorial, and publishing elites. Throughout the evening, Mailer refers to his interlocutors as “ladies,” whether to pull their tail feathers, as he might put it, or from sheer cluelessness. “Audience was clearly there for fireworks with some rabble rousers in attendance,” commented Variety. Ya think?

Sensing an opportunity for an advertisement for himself, Mailer recruited filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker, whom he had worked with on his misfired forays into celluloid, Wild 90 (1968) and Maidstone (1970), to document the evening. A graduate of the legendary Robert Drew unit, the pioneering practitioners of “direct cinema,” the fly-on-the-wall documentary movement the French would theorize and rename, Pennebaker preserved for history the kinds of events and performers that, at the time, no one else thought were profitable or important enough to film. These included Don’t Look Back (1967), the record of Bob Dylan’s back pages from his 1965 tour of England and the template for every performer-on-tour album ever since; and Monterey Pop (1968), the landmark concert film of the landmark flowers-in-your-hair concert. The rock and roll captured in Town Bloody Hall is of (slightly) lower decibel but very much of a piece with the aesthetics and ethos of the genre. Shooting in 16mm color, three cameramen covered the action with hand-held cameras; the sound was recorded separately, untethered from the cameras. Despite the limitations of 10-minute rolls of film, the cameramen seem to have caught most of the action, though every so often there’s a missed cue or abrupt transition.

Ceballos, head of the New York chapter of the National Organization for Women, speaks first. She is the face of nuts-and-bolts feminism, a representative of the women who did the heavy lifting of organizing and fundraising, painting signs and mimeographing leaflets, the necessary drone work of building a small grass roots movement into a popular uprising. A daughter of the Friedanian emphatically not Freudian revolution, she declares that the root of every political revolution is women’s liberation.

Ceballos has barely begun speaking when Beat generation poet Gregory Corso stands up and starts yelling from the back of the hall.

“Hey Gregory,” Mailer shouts. “You’ll get bounced. Keep it up.”

Actually, Corso bounces himself, exiting in a huff.

“There’s a woman outside who can’t afford to get in!” shouts a voice from the balcony.

“It’ll always be true until it’s not true,” shrugs Mailer.

Up next is Greer, introduced by Mailer as a “young and formidable lady writer” who was doubtless the big-ticket draw for the crowd. Tall, lean, and angular, she is far and away the most cinema-genic presence on-screen and also the speaker with the sharpest critical intelligence. If Mailer is the hot and hissable alpha male, (“I’m not gonna sit here and let you harridans harangue me”), Greer is the cool Valkyrie warrior, the flesh and blood antithesis of the title of her famous polemic, The Female Eunuch (1970), an attack on the nuclear family that landed like a nuclear explosion. When Greer calls Mailer “the pinnacle of the masculine elite” — which she does not mean as a compliment — Mailer beams. “No woman yet has been loved for her poetry,” she laments. “Diaper Marxism,” scoffs Mailer.

Germaine Greer and Norman Mailer taking a time out in Town Bloody Hall.

After the steely Germaine Greer, dance critic Jill Johnston (“the master of free associational verse in the Village Voice”) seems at first a bit goofy. However, the militant feminist, provocateur, and out-front lesbian (still a scandalous thing at the time) gets her groove on with a hilarious Beat-rap take-down of the patriarchs who apparently have begat each other from the days of the Old Testament to the administration of the current White House. “Until all women are lesbians there will be no true political revolution!” she declares. Johnston’s spiel runs long and Mailer tells her to wrap it up. Some members of the audience shout objections, demanding she be allowed to finish. Mailer takes a voice vote and decrees, fairly enough, that she lost a squeaker. By this time, a female companion has joined Johnston stage and the pair begin to hug and grope. A third woman gets into the act and the threesome roll about on stage. “Come on, Jill, be a lady,” Mailer pleads. After the mock (or not) dry humping, Johnston exits the stage, never to return. That was the night, Mailer later half-joked, that “Jill Johnston turned my hair gray.”

Diana Trilling (“our leading lady critic”) seems a figure from another age because, even in 1971, she was. A veteran of a quite different set of culture wars — the tension between liberalism and hard-leftism during the Cold War — she has other perspectives and priorities. Flaunting her authority as the reigning queen bee of the Old School New York intellectuals, she is deeply suspicious of the denial of biological difference promulgated by some wings of the feminist movement. She also casts a narrow eye on her younger, more radical sisters, especially Greer, the new kid in town, whom she treats with schoolmarmish hauteur, which naturally tightens Greer’s jaws. This is not to say Trilling is an over-the-hill prude not hip to the then-vital questions of the day, such as the viability of a purely vaginal orgasm. She gets off the biggest applause line of the entire night by declaring, “I could hope that we would also be free to have such orgasms as, in our individual capacity, we hope to be capable of.”

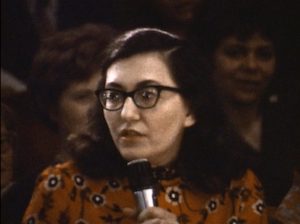

Susan Sontag questioning Mailer’s use of gendered language in Town Bloody Hall.

A good portion of the questioners at ringside could have been on the dais, tag-teaming the chosen quartet: Founding Mother Betty Freidan, author of The Feminine Mystique (1963) and the guru who inspired a million epiphanic “clicks” from postwar housewives; Susan Sontag, at peak gorgeousness, cringing at the use of the word “lady;” and Cynthia Ozick, deceptively demure and straight looking, who fires off the most lethal zinger of the evening — and brings the house down — by asking Mailer, “When you dip your balls in ink, what color is it?” Reeling from the sucker punch, Mailer replies sheepishly, “yellow” and wisely cedes the round to Ozick.

Throughout the cross fire, framed behind the table on stage in a cozy two-shot, Mailer and Greer radiate a palpable erotic buzz. During an exchange on the distinction between two nicknames for Mailer’s favorite organ (“The ‘retaliator’ is not quite so formidable as the ‘avenger,’” he informs her, grinning), Greer roars with laughter. “I’m afraid I’ll have to take a woman’s view of that,” she responds. If Town Bloody Hall were a screwball comedy, they would have wound up in bed together in the last reel.

Like many a barroom blowhard, Mailer had the disturbing tendency to utter a profundity midstream into the BS. At one point, he expresses trepidation about a totalitarian impulse in left-wing ideology, and a prophetic fear about a future where “the destruction of human liberty came not from the right but from the left.” In the present atmosphere, it may be instructive to note that the hecklers in the crowd disrupt the conversation only temporarily: they leave the hall in a huff, shouting deprecations (“Women’s lib is for rich bitches only!”), but it seems not to occur to even the angriest malcontents that they have the right to storm the stage and prevent the debate from going on.

Mailer also says that the totalitarian impulse in left-wing ideology “terrifies me because it’s humorless,” which is something that cannot be said of the assembly at Town Hall, who collectively give the lie to the canard about strident, tight-assed feminists lacking a sense of humor (cf., a popular joke that went around at the time: “How many feminists does it take to screw in a lightbulb?” “That’s not funny!”) When some hapless male in the crowd plaintively asks Greer the old question — what do women want? — Greer snaps, “Whatever it is they’re asking for, honey, it’s not you.”

The Criterion Collection is known for its choice supplements and the Town Bloody Hall edition is no exception. The extras include a 2020 interview with Chris Hegedus (her partner and husband Pennebaker died in 2019) discussing her role in editing and codirecting the film. After having the event filmed, Pennebaker put the film cans on the shelf, where the footage gathered dust until Hegedus came on board in 1976 to stitch it into coherent shape. Her goal was to shape the footage so you “would feel like you were at the event,” with the abrupt pans and tilts of the hand-held cameras imitating the spectator’s head while turning to look at a questioner or heckler. She trimmed the three-hour marathon into a tight 85-minute sprint.

Cynthia Ozick taking on Mailer’s chauvinism in Town Bloody Hall.

Also included on the extra menu is a reunion of the surviving female panelists (Trilling died in 1996), assembled for a post-screening discussion of Town Bloody Hall in 2004. Mailer did not attend and good thing too, cracks Greer, “because we’d be talking about that fucker all night.” Finally, not to be overlooked are the reflections from Greer and Mailer culled from Gerald Hofmann’s documentary See What Happens: The Story of D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus (2001), in which a laconic Greer recalls the evening, not without affection, as a “trivializing, perpetually silly sort of event in the best uptown tradition,” and Mailer looks back at the aborning second wave of the feminist revolution and compares himself to “the Czar’s nephew in 1917.” Chastened and self-aware, he admits, “I didn’t know what was going on.”

One last word of advice to not-just-the-hard-of-hearing: play the film with the subtitles on. Many of the best lines are shouted from the crowd and are muddled on the soundtrack. You don’t want to miss a word whispered, spoken, or hollered in Town Bloody Hall.

Thomas Doherty is a professor of American studies at Brandeis University and the author of Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century, due out from Columbia University Press this fall.

Tagged: Criterion Collection, Germaine Greer, Norman-Mailer, Thomas Doherty

Nice article, as always, from my friend, Tom Doherty. I would take issue with several sentences. One, Doherty calls Diana Trilling a “heavyweight feminist.” I certainly would not call her that, and I really doubt she would have labeled herself that way either. Discussing Trilling, Doherty talks of “the tension between liberals and hard-leftism during the Cold War.” I would change that to “the tension between liberal anti-communists and hard-leftism.” Doherty speaks of Norman Mailer’s “prophetic fear about a future where ‘the destruction of human liberty came not from the right but from the left.'” By calling it “prophetic,” is Doherty saying that Mailer is correct? At best, Mailer is partly correct, for there certainly are PC and “cancel culture” tendencies of some of today’s left which are reprehensible. Note that I said, some of the left. But Mailer is totally wrongheaded in predicting “the destruction of human liberty came not from the right.” Mr. Doherty: Donald Trump’s America, which you despise as much as I do.

Gerry

Thanks as ever for your careful reading. You recommended Town Bloody Hall to me when it was playing at the Brattle back in the day– you said that Greer and Mailer minded you of a couple in a Restoration play–

best TD

Norman Mailer may have wanted Diana Trilling on the panel because she respected his writing — though with justified reservations about his macho brand of American Existentialism, which excused violence in the name of a return to man’s primal self. Read her still interesting review of Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself in Claremont Essays. She was also most likely dead set against Kate Millet’s accusation in Sexual Politics that Mailer, Henry Miller, and D. H. Lawrence were anti-woman. She was an outspoken admirer of Lawrence’s, particularly his view that sexuality transcended politics: for Trillling, he knew “that sex is life itself. And he knew that life must be lived, not solved; that sex is a primary experience and not merely a means to an end. He knew that life is destroyed by program-making.” (“Men, Women, and Sex” in Claremont Essays.) This would have been anachronistic at the time (as were Mailer’s views). Trilling was far from a feminist critic — for which Millet was the pioneering model.