Film Review: “Azizler” (aka Stuck Apart) — Trapped Again

By Sarah Osman

Azizler is a slow burn; unfortunately, the payoff isn’t worth the wait.

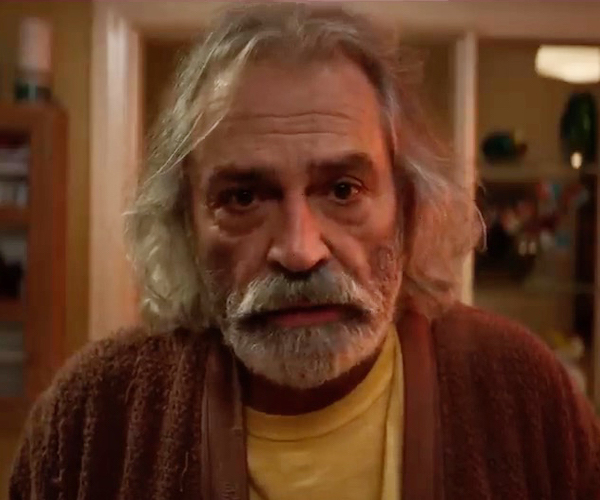

Aziz (Engin Günaydın) contemplating his limited options in Azizler. Photo: Netflix

Quarantine has confronted many of us with an existential crisis. The days seem to blur together, becoming a depressing version of the whirligig that is Groundhog Day. A flood of books and films are no doubt on their way to provide various reasons for being. But a movie has already come along and it ends up begging the big question: how do we escape an endless rut?

The Turkish film Azizler (Stuck Apart in English), now streaming on Netflix, couldn’t exactly be called a comedy — nor is it really a drama. It’s difficult to figure out in what genre to slot Azizler, but its meandering plot and offbeat characters are reminiscent of a Noah Baumbach film. It is definitely paced like a Baumbach effort. Azizler is a slow burn; unfortunately, the payoff isn’t worth the wait.

The plot centers on Aziz (Engin Günaydın), a middle-aged marketing executive whose life is a bit of a mess. His sister, brother-in-law, and their horrible son all live in his apartment. On his job he is surrounded by annoying coworkers he struggles to communicate with. He’s unhappy with his long-term girlfriend and wants to break up with her. In an early scene, he attempts to end things at a café, but she keeps asking him why he isn’t wearing the necklace she gave him. She obsesses on this gift: “You promised me to wear it all the time, where is the necklace?” The woman turns into a broken record. When Aziz understandably leaves the café, she remains in the same spot, repeating “You promised me to wear it all the time, where is the necklace?”

These moments set the static tone for the rest of the film. It’s as though Groundhog Day was played out over the course of a year as opposed to a day. The catch is that, unlike Bill Murray’s Phil, Aziz doesn’t seem to change in any measurable way.

Some of Azizler’s most entertaining moments are generated by Aziz’s terror of one of his nephews, Caner (Goktug Yildrim). The kid threatens to kill Aziz if he doesn’t play Legos with him. He also swears like a sailor and beats his father with a pull-up bar. Caner’s parents refuse to discipline him. In fact, Aziz is the only one in the family who perceives just how awful Caner is, suggesting that the boy should be taken to a psychologist. In one of the film’s most amusing scenes, the shrink informs Caner’s parents that he is a “jerk.” They weep in disbelief at the news and refuse to accept responsibility for Caner’s “condition.” It’s unclear how this conflict fits into the film’s overall theme, other than that a failure to teach kids personal responsibility will turn them into creeps. It’s a funny idea, but underdeveloped — perhaps because it raises uncomfortable political issues about accepting brutality?

Aziz’s coworkers are not aggressive but deeply lonely. His boss, Alp (Öner Erkan), is desperate to become friends with Aziz. He even throws a fake New Year’s party — made up of purchased party guests and a hired DJ — to induce Aziz to hang out with him. He invites Aziz to come over to his giant mansion anytime. Why is Alp so fascinated with Aziz? No reason, aside from the fact that he badly wants company. And Alp remains stuck in this cell throughout this meandering movie — he never becomes anything more than Aziz’s lonely boss.

Aziz’s older coworker, Erbil (Haluk Bilginer), is a more touching case. Aziz considers the aging widower a bit odd. He pines after one of his coworkers and welcomes memories of his loving wife. That is realistic enough behavior. But his wife, who died from cancer, comes back to “life” via a photo of her that’s pinned on Erbil’s fridge. She dispenses bits of advice (in the process she manages to scare off his new paramour). Erbil is trapped. He is desperate to move on, but he is held back (literally) by his love for his dearly departed wife.

There is comedy along with pathos in Azizler, some sight gags and clever lines, though they are spread too far apart to generate much momentum. Given all the domestic turmoil, the scenes where Aziz escapes his crazed family for a few moments alone are endearing, especially when he does a celebratory dance around a rich coworker’s house. Alas, Aziz’s problems take up most of the screen time; there is no exploration of what would have happened if the beleaguered guy had actually tried to change. Azizler seems to have surrendered to the mundane that is quarantine — the film takes us round and round the hamster wheel.

Sarah Mina Osman is a writer living in Los Angeles. She has written for Young Hollywood and High Voltage Magazine. She will be featured in the upcoming anthology Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences under the Trump Era.