Book Review: “How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year”

By Chelsea Spear

Music fans who miss, or missed, the long party that was mainstream music in the mid-’80s will be skillfully taken back to fast times in Can’t Slow Down.

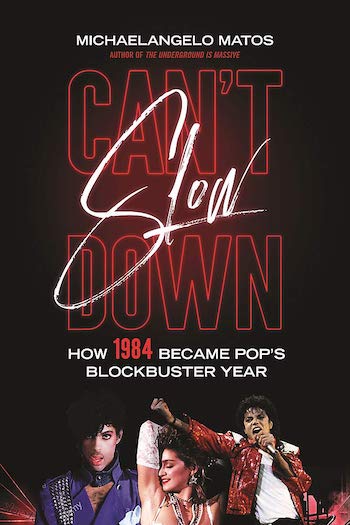

Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year by Michaelangelo Matos. Hachette, 480 pages, $30

Buy at Bookshop

From a remove of three decades, the ’80s pop music scene looks like one long party. Musicians like Madonna, Prince, and Bruce Springsteen became epoch-defining figureheads, and Michael Jackson — who was already iconic from his time in the Jackson 5 and his platinum-selling album Off the Wall — made the Guinness Book of World Records by selling over 20 million copies of Thriller. New genres of music were created, while innovative countercultural movements like punk and hip-hop broke through to mainstream audiences. Two networks were created to broadcast music videos. Michaelangelo Matos takes illuminating stock of the mid-’80s music boom with Can’t Slow Down, a retrospective on the blockbuster year of 1984.

From a remove of three decades, the ’80s pop music scene looks like one long party. Musicians like Madonna, Prince, and Bruce Springsteen became epoch-defining figureheads, and Michael Jackson — who was already iconic from his time in the Jackson 5 and his platinum-selling album Off the Wall — made the Guinness Book of World Records by selling over 20 million copies of Thriller. New genres of music were created, while innovative countercultural movements like punk and hip-hop broke through to mainstream audiences. Two networks were created to broadcast music videos. Michaelangelo Matos takes illuminating stock of the mid-’80s music boom with Can’t Slow Down, a retrospective on the blockbuster year of 1984.

Matos doesn’t open his study with a splashy awards ceremony, but starts off with a description of the recession the music industry weathered in the early ’80s. When radio stations decided to depend on preselected playlists that catered to narrow demographics, they found themselves chasing smaller, more specialized numbers of listeners. This was amid other ad news: disco, the industry’s previous cash cow, had gone down in flames, leaving nothing to fill the void; corporate rock bands, which Matos describes as “adult baby food,” had taken over the Top 40 but failed to connect with audiences in a meaningful way; and the Moral Majority had commenced to target the “decadence” of the music industry. While working on Michael Jackson’s second solo album Thriller, producer Quincy Jones remarked that “if we get six million out of this, I’m gonna declare that a success.” By foregrounding the pain of the early ’80s music-industry recession, Matos sets up a dramatic comeback that makes the excesses of 1984’s sales even more dazzling.

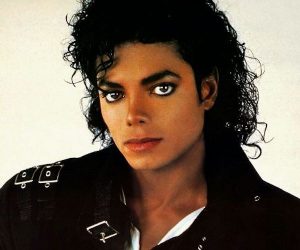

If Can’t Slow Down had a protagonist, it would be Michael Jackson. Matos’s story gains considerable momentum in a chapter set at the 1984 Grammy Awards, where Jackson wins a record-breaking nine Grammys. Though the promotional cycle for Thriller has started to wind down, Jackson would join his brothers on the Jacksons’ Victory tour, whose promotion and ticketing were the subject of some controversy among fans. Matos humanizes Jackson by showing his petulant and vulnerable sides, while acknowledging the unusual behavior that would become dangerous in later years. Writing about 12-year-old TV star Emmanuel Lewis, Jackson’s plus-one to the Grammys, Matos observed that “no one was publicly questioning Michael’s motives for being around those kids yet — that wouldn’t surface for a decade. Michael was a showbiz kid and liked being around others.” Jackson’s involvement with the ill-fated Victory tour gives Matos an opportunity to examine the creeping corporate influence on large pop tours. “Speaking to Advertising Age in 1981, (promoter Jay) Coleman credited the sudden corporate prominence of ‘The Woodstock Generation’ — yuppies with dollars to spend — for these campaigns’ success.”

Michael Jackson — the protagonist of pop in the mid-’80s?

Can’t Slow Down is at its most effective when Matos finds parallels between music and politics. He opens a chapter on Talking Heads — who were at their peak with the groundbreaking concert film Stop Making Sense — by noting that “rock singers didn’t sing about stockbrokers sympathetically until (Talking Heads leader) David Byrne came along,” perceptively pointing out the similarities between the privileged speaker in Byrne’s lyrics and those of the band’s upwardly mobile fans. In addition, a chapter on Bruce Springsteen’s political beliefs looks beyond the patriotic imagery of the Born in the USA album to examine how the presumably liberal singer’s politics were (surprisingly) open to interpretation. “Springsteen played benefits like 1979’s No Nukes, his songs were full of explicit political commentary, his entire act a tribute to the workingman and -womanbut songs like ‘The Promised Land,’ with their explicit adherence to old-fashioned values in the face of a changing world, were, however nuanced in the writing and despite Springsteen’s affinities and alliances, easy to take as face-value conservativism.”

1984 also saw the music business grow more diverse in age and race. “The rock biz’s long-standing directive to sell to teenagers, seen as the music’s natural constituency, was beginning to change shape,” the author observes. As the Baby Boomers grew older and the pop music audience became more diverse, the industry evolved to reach nontraditional listeners. Matos devotes a chapter to how Island executive Dave Robinson revolutionized the reissue market with the Bob Marley compilation Legend, which, “from a marketing point of view was to sell him [Marley] to the white world.” Legend was also an effective spur to the growing American interest in “world music,” a subject that generates considerable heartbreak in Can’t Slow Down as different executives attempt to sell such disparate non-English-speaking stars as Ruben Blades, King Sunny Ade, and Fela Kuti as the next Bob Marley.

At 480 pages, this book clocks in as a tome, with Matos feeling duty bound to cover as much musical territory as possible. A lot of material is covered here, but the writer’s nimble writing style and wry observations make what could have been a dense history a pleasure to read. Music fans who miss, or missed, the long party that was mainstream music in the mid-’80s will be skillfully taken back to fast times in Can’t Slow Down.

Chelsea Spear has written for the Brattle Theatre’s Film Notes blog, the Gay & Lesbian Review, and Crooked Marquee. She lives in Boston.

Tagged: Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year, Chelsea Spear, Michael Jackson