Opera CD Review: William Alwyn’s Powerful Take on Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” — A Neglected Masterpiece

By Ralph P. Locke

The second recording of William Alwyn’s searing opera confirms the work’s vitality and importance. It is one of the best and most accessible operas to have been written in the past few decades.

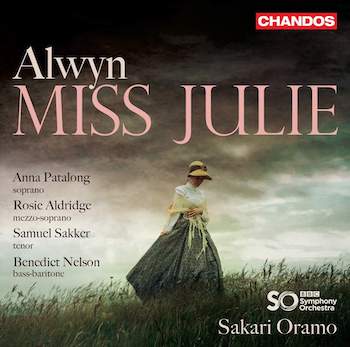

William Alwyn: Miss Julie

Anna Patalong (Miss Julie), Rosie Aldridge (Kristin), Samuel Sakker (Ulrik), Benedict Nelson (Jean).

BBC Symphony Orchestra, cond. Sakari Oramo.

Chandos 5253 [2 CDs] 87 minutes

To purchase, click here.

Here, in less than an hour and a half, is a remarkable opera that deserves more attention than it has gotten. The composer, William Alwyn (1905-85), is best known for his film scores (some 70 or more) and symphonies. In his later years, he composed two operas, in which he sought to combine his mastery of the orchestra with his equally extensive experience (from writing for films) in using music to reflect character and drama. Juan, or the Libertine (based on the Don Juan legend) has never been recorded, but Miss Julie (based on the famous Strindberg play and completed in 1976) did get released, in a recording made in the famous Kingsway Hall in 1979.

Here, in less than an hour and a half, is a remarkable opera that deserves more attention than it has gotten. The composer, William Alwyn (1905-85), is best known for his film scores (some 70 or more) and symphonies. In his later years, he composed two operas, in which he sought to combine his mastery of the orchestra with his equally extensive experience (from writing for films) in using music to reflect character and drama. Juan, or the Libertine (based on the Don Juan legend) has never been recorded, but Miss Julie (based on the famous Strindberg play and completed in 1976) did get released, in a recording made in the famous Kingsway Hall in 1979.

(Sidelight: In the TV show The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Sophie Lennon, an arrogant professional comedienne who is utterly inexperienced at working with other performers, bizarrely yearns to star in a production of this naturalistic Strindberg play, which requires highly responsive interactions with the other actors on stage.)

Alwyn’s Miss Julie has been staged a single time (1997), yet its reputation as a major statement has now won it a second recording. The new recording was, like the first, made under studio conditions. It was preceded, a few weeks earlier (October 2019), by a semi-staged concert performance in London’s Barbican Hall (October 2019).

The critic for the London Times wrote, after the concert: “Why has this intense, brilliantly orchestrated, claustrophobically gripping masterpiece been so neglected since its 1977 premiere?” Why, indeed! I am at a loss for words to describe Alwyn’s powerful musical drama, for which he himself condensed Strindberg’s play into one of the strongest operatic librettos I have ever encountered.

There are only four characters, and the entire action takes place in the kitchen of the country estate of a Swedish count. Miss Julie, who is the count’s twenty-something daughter, is attracted by her father’s valet, Jean (thirtyish), but he has long promised to marry Kristin, the count’s cook. The opera takes place over the course of a day and the following morning. Julie and Jean go dancing and then make love in a bedroom offstage. (The count is away on a trip.) Julie steals the count’s money so she and Jean can leave together and run a hotel in Lugano (in southern Switzerland). Jean, for no apparent reason, has Julie’s dog killed by Ulrik, the gamekeeper. (The character Ulrik was added by Alwyn, a brief but effective expansion.)

When the count unexpectedly returns (though he never appears onstage), Jean puts on his valet uniform again, declaring to Julie that the plan to elope was a dream and calling her a “slut.” Distraught over the dog’s death and Jean’s betrayal, Julie asks him what she should do. Jean suggests that she commit suicide, as her mother did, and indicates his razor on the table. She asks him for a kiss, but he curtly refuses and leaves the kitchen. Julie picks up the razor and walks out into the park as the curtain falls.

Strindberg’s drama has been praised for its emphasis on the meaningless life of the well-to-do and the greater vitality of the lower classes. It has been regarded as anti-feminist but also as subversively feminist: Julie does try to break out of her confining existence, and Jean turns out to be as cold a brute as literature provides: a symbol of what women are often up against in life. I suppose the play — I’ve never seen it staged — is all those things and more, as is of course true of any complex work of art. Alwyn’s opera follows suit, suggesting that Julie lacks a constructive outlet for her energy and passion, and that the lower classes, as embodied in the valet Jean, possess a strong will but can also engage in casual cruelty.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chief Conductor Sakari Oramo perform William Alwyn’s take on Strindberg’s Miss Julie at the Barbican Hall on 3rd October 2019. (Anna Patalong Miss Julie, Benedict Nelson, Jean). Photo: Tom Howard.

The opera moves forward with such taut inevitability that I can imagine it having quite a life in the concert hall. I’d urge that it be tried on stage as well. With only four singing roles and a very colorful orchestra, it would prove a highly effective offering at a regional opera company or first-rate university music school. I don’t think the vocal parts would be beyond the capabilities of good young professionals, though, in the first recording (to judge by the excerpts that I have listened to), Jill Gomez and Benjamin Luxon — major artists — brought special glamor and insight to the roles of Julie and Jean. Conducted by Vilem Tausky, that recording remains available inexpensively on Lyrita. Its booklet includes the libretto and a good essay.

Alwyn’s music is immensely attractive: basically tonal but also bringing in highly dissonant passages (as at the very beginning) to emphasize the tensions and darkness in the plot. Some purely orchestral passages recall Debussy: I think I noted a resemblance between the prelude to Act 1 Scene 2 and something in The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Other passages evoke a distorted waltz, because of events that are referred to: Miss Julie having danced at a party with Ulrik, then with Jean, and then clandestinely going off to dance with Jean again, though he had promised to take his fiancée Kristin instead. At such moments, I was suddenly reminded how close a modern opera, written in a largely tonal style, can be to a musically sophisticated Broadway musical such as Sondheim’s A Little Night Music.

Soprano Anna Patalong manages to be alternately imperious and tender as the title character, creating a real person in front of our, well, ears. But her voice is on the small side and somewhat unfocused (quite unlike Jill Gomez’s intense precision), so I had to look at the libretto frequently when Patalong was trying to sing loudly over a full orchestra. Also, she has a touch of wobble on some long notes; I hope she will gain a bit more control so as to maintain a long career. For contrast, just listen to Miss Julie’s longest solo, “Midsummer Night,” as sung by Patalong, by Gomez on the Lyrita recording or, even better, by Kate Royal (on a 2009 aria recital bearing the same title as that aria, Warner Classics 2681922). Gomez and Royal each have near-perfect vocal control, and their words can be made out far more easily.

As Kristin, the cook, mezzo-soprano Rosie Aldridge displays a solid voice and oodles of personality. I could understand her every word. Bass-baritone Benedict Nelson carries off the role of the manipulative valet with immense authority, all the more remarkably given that he was brought in as a late replacement 48 hours before the Barbican performance. Particularly vivid are his imitations of the snippish orders given by the Count. (So we do get to hear the Count, by proxy.) Light tenor Samuel Sakker turns the small role of Ulrik, the gamekeeper, into a credible character: smug and petty.

Yes, I dislike all these people, except maybe Kristin.

The conducting (by Finnish-born Sakari Oramo) and the orchestral playing seem solid and appropriate, though nothing here or on the Lyrita recording compares to the glowing sonorities that Edward Gardner gets out of the Orchestra of the English National Opera on that 2009 Kate Royal aria disc.

Chandos helps by including the libretto and an essay and synopsis. (The latter two, full and nuanced, are by Andrew Palmer.) There are 48 tracks — each, on average, shorter than two minutes, and identified by the character who is first heard singing and by his or her opening words. Thus one can easily jump ahead or back with a remote control and become increasingly familiar with certain passages.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chief Conductor Sakari Oramo perform William Alwyn’s take on Strindberg’s Miss Julie at the Barbican Hall on 3rd October 2019. (Benedict Nelson, Jean, Rosie Aldridge, Kristin). Photo: Tom Howard.

I am delighted to discover what Alwyn could do away from the film studio: his Miss Julie must be one of the best and most accessible operas to have been written in the past few decades, which is not to deny its repulsive aspects. And now we have two very credible recordings to choose from and compare — quite a treat!

(Both recordings are, I believe, available as physical CDs, as downloads, or through subscription streaming services such as Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube Premium. Individual tracks can be found at the free YouTube site. One can sample the beginning of each track of either recording at such sites as Presto Classical, HBDirect, and ArkivMusic. If you subscribe to Naxos Music Library, you can stream either this recording or the Lyrita and download the respective booklet, complete with libretto.)

I’d love to see Alwyn’s Miss Julie staged, whenever the day comes that we can have staged opera again. It even occurs to me that this opera could be performed with singers standing ten or more feet from each other, considering how disconnected — “emotionally distanced” — they are from each other.

Experiencing Alwyn’s opera has now made me eager to get to know Ned Rorem’s opera based on the same play. It is likewise available in two recordings!

To my readers: What recent or unusual opera has caught your ear? Share the good news in the Comment box….

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Anna Patalong, Chandos, Miss Julie, Ralph P. Locke, Sakari Oramo