Classical CD Reviews: Listening During COVID, Part 3 –From Boston with Love (Performances of Haydn, Dello Joio, and Virgil Thomson).

By Ralph P. Locke

Two new recordings and one much-welcome re-release contain first-rate performances of Haydn’s 1798 “Lord Nelson” Mass, Dello Joio’s opera about Joan of Arc, and Virgil Thomson’s astonishing musical portraits of Alice B. Toklas, Picasso, and others.

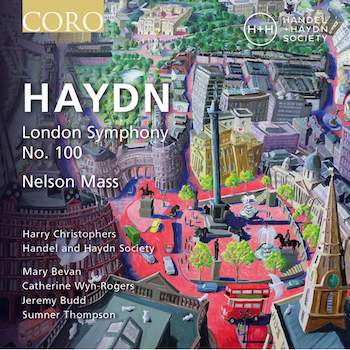

Haydn, Symphony No. 100 (“Military”) and Mass No. 11 in D Minor (“Missa in angustiis,” or “Lord Nelson Mass”), period instruments, c. Harry Christophers.

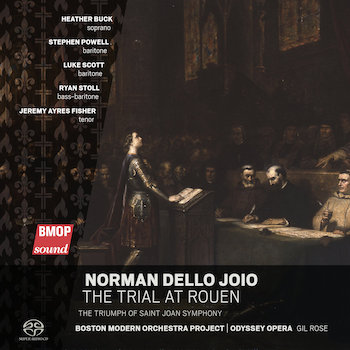

Dello Joio: The Trial at Rouen (TV opera, first recording). Odyssey Opera, cond. Gil Rose.

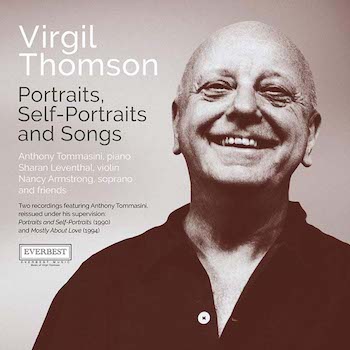

Virgil Thomson: Portraits, Self-Portraits and Songs. Anthony Tommasini, piano, and others.

As the Covid pandemic continues, I remain within our apartment’s four walls for most of every day, and have come to appreciate even more than before the warmth, vibrancy, and variety of moods that music can bring.

This third installment of my report on recent record releases focuses on three CDs (or CD-sets) featuring Boston-area performers. I cheated: one of them is a 2-CD re-release of 1990s-era recordings of music by Virgil Thomson. I never acquired those CDs the first time, and I am particularly grateful that they are available again.

(The three releases discussed below are available as physical CDs, as downloads, or through subscription streaming services such as Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube Premium. Certain individual tracks can be found at the free YouTube site. One can sample the beginning of each track of the three recordings reviewed here at such sites as Presto Classical, HBDirect, and ArkivMusic.)

Click here to purchase the Haydn, the Dello Joio, or the Thomson.

Let me start with one of the most renowned works of Franz Joseph Haydn: the so-called “Lord Nelson Mass.” Haydn’s Mass No. 11 in D (1798) apparently received the nickname because news of Nelson’s victory over Napoleon’s troops (at the Battle of the Nile) arrived shortly before the mass’s first performance. Haydn himself called it “Missa in angustiis,” which can mean any of several things: for example, “Mass in Times of Anxiety” of “Mass in Time of Fear.” It may also refer to Haydn’s health, which was poor at the time. Or to the fact that the Eszterházy family had dismissed the woodwind players in order to economize, thus forcing Haydn to use a smaller orchestra, consisting only of strings, brass, timpani, and organ. But he made the most of his resources, including some startling passages for brass and (in the Gloria) a mellifluous oboe-like solo for the organist’s right hand. The “missing” woodwind parts were created after Haydn’s day to bring the work into line with his normal scoring, but conductors today tend to avoid them and thereby preserve the work’s distinctive sound.

Let me start with one of the most renowned works of Franz Joseph Haydn: the so-called “Lord Nelson Mass.” Haydn’s Mass No. 11 in D (1798) apparently received the nickname because news of Nelson’s victory over Napoleon’s troops (at the Battle of the Nile) arrived shortly before the mass’s first performance. Haydn himself called it “Missa in angustiis,” which can mean any of several things: for example, “Mass in Times of Anxiety” of “Mass in Time of Fear.” It may also refer to Haydn’s health, which was poor at the time. Or to the fact that the Eszterházy family had dismissed the woodwind players in order to economize, thus forcing Haydn to use a smaller orchestra, consisting only of strings, brass, timpani, and organ. But he made the most of his resources, including some startling passages for brass and (in the Gloria) a mellifluous oboe-like solo for the organist’s right hand. The “missing” woodwind parts were created after Haydn’s day to bring the work into line with his normal scoring, but conductors today tend to avoid them and thereby preserve the work’s distinctive sound.

Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society makes the most of the “Nelson” Mass, in the original, woodwind-less scoring, which sounds all the more colorful thanks to the period instruments that the orchestra has used since 1986 (when Christopher Hogwood became their music director). Harry Christophers, who has been music director since 2009, keeps the tempos forward-moving and the textures clear. The superb acoustics of Symphony Hall surely help!

The four vocal soloists, three of them from Great Britain, capture the work’s forthright spirit, though the bass—the one American—lacks strength in his low notes (like so many low-voiced males in the opera and oratorio world these days, as Conrad L. Osborne rightly complained in his recent book Opera as Opera: The State of the Art). The soloists are, if anything, outshone by the splendidly alert HHS chorus. Famous recordings by David Willcocks and Richard Hickox now have a second worthy companion that is “made in Boston” to stand next to the equally fine version from Boston Baroque (with a particularly marvelous and bright soprano: Mary Wilson) under Martin Pearlman.

The CD is filled out with Haydn’s Symphony No. 100 in G Major (1793 or 1794), whose nickname “Military” refers to the prominent role that (again) brass and percussion play—here, in the slow movement and the finale. Christophers and HHS have gone an extra mile to bring appropriate instrumental clamor to those moments: the recording uses a modern replica of a Turkish crescent (a kind of bell-tree, also known as a “jingling johnny”) based on one that can be seen in the music-instruments room of the Museum of Fine Arts, a newly built drum modeled on the proportions of a Turkish davul, and other percussion instruments (a pair of cymbals and a triangle) that, as was typical in Haydn’s day, have a sound deeper than that of their modern equivalents.

Boston’s adventurous Odyssey Opera, under intrepid conductor Gil Rose, brings us a world-premiere recording: the 1955 opera The Trial at Rouen, by American composer Norman Dello Joio (1913-2008), who taught at Boston University for many years. Dello Joio was repeatedly drawn to the inspiring legends surrounding Joan of Arc (ca. 1412-31). He wrote an opera entitled The Triumph of Saint Joan (1950), then adapted that into a three-movement symphony with the same title (which Martha Graham would use for a dance entitled Seraphic Dialogues). Then he wrote a largely new opera, The Trial at Rouen, for telecast on NBC Opera Theatre. Finally, he expanded that opera somewhat, retitled it The Triumph of Saint Joan (i.e., re-using the title of the first opera and the symphony!), and it got performed by the New York City Opera.

Boston’s adventurous Odyssey Opera, under intrepid conductor Gil Rose, brings us a world-premiere recording: the 1955 opera The Trial at Rouen, by American composer Norman Dello Joio (1913-2008), who taught at Boston University for many years. Dello Joio was repeatedly drawn to the inspiring legends surrounding Joan of Arc (ca. 1412-31). He wrote an opera entitled The Triumph of Saint Joan (1950), then adapted that into a three-movement symphony with the same title (which Martha Graham would use for a dance entitled Seraphic Dialogues). Then he wrote a largely new opera, The Trial at Rouen, for telecast on NBC Opera Theatre. Finally, he expanded that opera somewhat, retitled it The Triumph of Saint Joan (i.e., re-using the title of the first opera and the symphony!), and it got performed by the New York City Opera.

I suppose the telecast of the version heard here survives somewhere in the NBC vaults (it featured the always-gripping Elaine Malbin), or in videorecordings made by alert home viewers. I’d love to see it, but I doubt that it could surpass what Gil Rose and his Odyssey Opera provide. The orchestra is the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, of which Rose is likewise the music director. The music turns out to be attractive and keenly responsive to the flow of the drama (the composer wrote the libretto himself). Its melodic lines—in voices and orchestra alike—are redolent of Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony. The singers, all first-rate, convey the texts with nobility and clarity. Happily, the release comes with a libretto, in case there are a few words that you can’t catch.

Particularly admirable are Heather Buck as the determined (or stubborn or self-destructive—discuss!) Joan and baritones Stephen Powell and Luke Scott as Bishop Pierre Cauchon and Father Julien: respectively, the harsher and gentler representatives of the church. The latter two convey dignity and determination through steady, beautiful tone and precise diction. The big scene between Joan and Father Julien in Act 1, the latter hoping to persuade her to recant, could be a major item on duet recitals at music schools. And Joan’s pained soliloquies toward the end of each of the opera’s two scenes would reward inclusion in an album of soprano arias.

The third Boston-based recording that brightened my recent weeks is a re-release of two CDs of music by the composer and critic Virgil Thomson. I love his rather bizarre opera Four Saints in Three Acts, of which the most recent recording is by Gil Rose’s crew.

CD 1 in this re-release is a collection of portraits-in-music that Thomson created in real time: he would write the notes on music paper while the person in question was sitting nearby, perhaps reading a book. The sitters included Copland and other musician friends or patrons, Gertrude Stein’s life-companion Alice B. Toklas, and (a double-portrait) Dora Maar and Picasso. Many of these pieces are for solo piano or one instrument plus piano. One became a short flute concerto, from which we hear the opening movement, which is for unaccompanied flute.

CD 2 gathers many of Thomson’s songs, often to playful and slightly puzzling texts, to which his music reacts with its own amusement. I was occasionally reminded of Satie and Poulenc, no surprise given Thomson’s early years in Paris and his lingering affection for French music of the early twentieth century. These songs offer modernism-without-tears, a combination that we rarely encounter. More serious sorts — Schoenberg, Boulez, Stockhausen — may have thought such music insufficiently weighty or systematic, or just undignified. (There are numerous echoes of dance music of various eras.) But, in this post-modernist age, Thomson’s light-on-its-feet manner creates sequences of sounds that are intriguingly unpredictable and, decades later, still as fresh as dew.

CD 2 gathers many of Thomson’s songs, often to playful and slightly puzzling texts, to which his music reacts with its own amusement. I was occasionally reminded of Satie and Poulenc, no surprise given Thomson’s early years in Paris and his lingering affection for French music of the early twentieth century. These songs offer modernism-without-tears, a combination that we rarely encounter. More serious sorts — Schoenberg, Boulez, Stockhausen — may have thought such music insufficiently weighty or systematic, or just undignified. (There are numerous echoes of dance music of various eras.) But, in this post-modernist age, Thomson’s light-on-its-feet manner creates sequences of sounds that are intriguingly unpredictable and, decades later, still as fresh as dew.

The 2-CD set features performers who were largely Boston-based at the time, most centrally the pianist Anthony Tommasini, now chief music critic at the New York Times, but also such familiar names as flutist Fenwick Smith and tenor Frank Kelley (whose vivid participation I greatly enjoyed in the recent world-premiere recording of Carlisle Floyd’s opera Prince of Players). Tommasini’s original booklet-essays are reprinted. The 1990s-era bios for the performers remind us how prominent some of these musicians already were at the time. The three hours of music so beautifully served up here helped brighten several cold and dreary mornings for me during the past weeks.

I ask my readers: what new or unusual items have helped you get from day to day recently? I specify new or unusual, because of course we all have our favorite oldies: say, Glenn Gould’s first Goldberg Variations recording, or Maria Callas’s first Tosca, under De Sabata.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Gil-Rose, Handel and Haydn Society, Lord Nelson” Mass, Odyssey Opera, Ralph P. Locke, The Trial at Rouen, composer Norman Dello Joio

Thanks for mentioning Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts, written with Gertrude Stein. It has an interesting history and doesn’t get the attention it deserves. It’s quirky and pretty much nonsensical, but lots of fun! I’d like to check out the Virgil Thomson CDs you mentioned. Do you know if they are available for streaming or only as a CD?

Two rare favorites come to mind. Not in the classical area. One is “Music for the Knee Plays”, by David Byrne (of Talking Heads fame). I searched for it for years and finally found a CD for purchase online, and have since lost it again! Lots of delightful music heavily featuring brass instruments and clever lyrics. Unlike anything else you’ll hear, but loads of fun.

If you love David Byrne, his project Love This Giant (with St. Vincent) is also heavily brass-infused and under-appreciated.

Another hidden gem that comes to mind is a CD called Requited, by Bert Seager. It’s based on a previous jazz piano CD Bert recorded. His friend Anita Diamant, the author, asked if she could put words to the music, and he said no! After she asked a few more times, he relented. The music to me sounds like it’s from some other era. Never got much attention, I don’t think, and it’s not like anything else you’ll hear. Some pieces are upbeat, but many of the tunes have a wistful or melancholy theme. Great jazz instrumentals and great vocals by Rebecca Shrimpton (challenging arrangements!). Maybe I just like it because I know Bert. :-). But it’s been in my playlist for 12 years now, and I’m always happy when it comes up.

While I’m at it, I will mention my favorite movie, Diva, which I rarely see mentioned. Takes place in France, in French with subtitles; an intriguing plot based on a stolen performance tape, as I recall, and great cinematography.

I’ll stop there. Maybe not exactly what you were looking for, Ralph, but a couple music gems for your consideration.

Mike

Thanks for these somewhat offbeat suggestions, which was what I was hoping for!

Yes, nearly all the recordings that I review here are now available through various streaming services, such as Spotify and Apple Music.

Many of them are also on YouTube, for free, as single tracks–and as albums if you subscribe.

For Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s “Four Saints in Three Acts” I strongly recommend the abridged recording conducted by the composer. Some of the singers are ones who sang those same roles in the original production. They often show more personality and specificity than do the singers in more recent recordings. I find it available online (as an import) at https://www.hbdirect.com/album_detail.php?pid=208211.