Poetry Review: Gail Mazur’s “Land’s End” — Poems of Questions and Declarations

By Jim Kates

It’s hard to imagine many of Gail Mazur’s poems emerging from anywhere else than from inside Route 128.

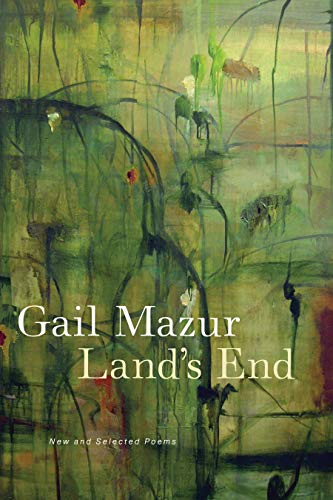

Land’s End by Gail Mazur, University of Chicago Press, 208 pages, $25.

Buy at Bookshop

Before I had received Gail Mazur’s Land’s End, it had already been praised to me as an artifact, a book that looks and feels handsome. In this day of cookie-cutter template publication and undistinguished design, that’s already a quality to celebrate, and not simply incidental to the poet’s own work. At the heart of Mazur’s poetry is an appreciation of aesthetics; she has been a poet who surrounds herself with artists like Kai,

carving for me two perfect maple caps,

one for now, one for the future, when he knows

in his heart I’ll need another.

(“Blue Umbrella”)

The poems echo with names not so much dropped as cradled, passionately recalled. And foremost among these, her late husband Michael Mazur, whose presence and absence animate so many of the more recent poems. “asleep until noon,” Mazur writes in “Forbidden City,” “I’m dreaming / we’ve been granted another year…. I wake, I hold your hand, you let me go.”

Living on here,

I have what I have, an acceptance of loss that disappears in dreams,

in excruciating replays of a life draining away — these visitations,

like falling trees unsummoned come, my night a crushing yesterday

the lit bed-light won’t erase or wish away —

(“At 4 a.m.”)

And, as with Kai’s craftmanship, there are many arts.

The last poem in the book, the one by which the poet is best known, has entered into the classic American canon. “The game of baseball is not a metaphor / and I know it’s not really life,” the speaker of “Baseball” announces with insistent litotes, but “the wind keeps carrying my words away.” It is also the most public poem in the book, the “I” being so much more expansive than a single perception.

Then, as the speaker’s voice moves forward in years (backward in pages) it becomes more personal and intimate, until Mazur begins her collection by looking at and into a mirror, a “half-conscious glimpse of myself / on my way out for a walk in February snow, / with a friend, or alone . . . ”

Then, as the speaker’s voice moves forward in years (backward in pages) it becomes more personal and intimate, until Mazur begins her collection by looking at and into a mirror, a “half-conscious glimpse of myself / on my way out for a walk in February snow, / with a friend, or alone . . . ”

(It’s not that I want to read the book backwards, but that I have long since read most of it backwards. I have encountered the majority of these “selected” poems in the collections they originally came out in, and this compilation is organized retrospectively.)

For those of you who read the book forwards, the way it is structured, I urge you to hurry through that latest, first poem, “Hall Mirror.” It’s more than just personal, intimate: on its own, it sounds smug, the mirror “preserving and inventing the past — / for what? // For me.” I can only hope the intent is ironic, but there’s no context for it yet.

But read beyond “Hall Mirror.” By the time you get to the very next poem, “At 4 a.m.,” you’re beginning to enter the world with the poet by your side (that “crushing yesterday / the lit bed-light won’t erase or wish away —”), and the poems take on breadth, until the “New Poems” section ends in elegy, in ache, “Too late, too late, more, more / the god-gull shrieks swooping down / to tear at the tender shell.”

And now you can move into Mazur’s retrospective. Her personality, her intimacy, is also local. It’s hard to imagine many of these poems emerging from anywhere else than from inside Route 128. Their assumptions are those of Cambridge and Newton, even when the speaker travels as far as Houston, Japan, or Cape Cod. The Charles River “flowed through my childhood,” and we have no doubt that the speaker here is the poet herself.

Very few poems venture into another voice, or focus strongly on another person’s perspective. “Michelangelo: to Giovanni da Pistoia…” reads as if it were found in, not constructed from, the artist’s correspondence:

My haunches are grinding into my guts,

my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight,

every gesture I make is blind and aimless.

But the title poem of her 2005 collection Zeppo’s First Wife brilliantly interweaves the public third-person and the personal first-person of Mazur’s own voice. And a portrait of “Isaac Rosenberg” contains one whole life in two pages, winding at last to the poet’s “I” and thumping to a sudden domesticity: ” …he taught Jonny some Yiddish I’d never heard / him speak a word of, and that way / helped him pass his graduate German exam.”

After all, that’s where the strength of these poems remains, in the questions and declarations Mazur propounds that “pull me mercifully back / to my calm, impenitent room.”

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Paper-thin Skin (Zephyr Press), a translation of the Kazakhstani poet Aigerim Tazhi.