Book Review: “Sittin’ In” — Remembrance of Jazz Clubs Past

By Steve Provizer

Sittin’ In raises fascinating issues and its wealth of ephemera provides an amusing context in which to ponder deeper questions.

Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s by Jeff Gold. Harper Design, 260 pages, $39.99.

Buy from Bookshop

Sittin’ In belongs to the family of large-format jazz-related books like The Jazz Image: Masters of Jazz Photography and Impulse for Change: The Story of Impulse Records. The volume is text-heavier than the former and more graphics-heavy than the latter. Author Jeff Gold breaks the book into sections — “The East Coast,” The Midwest” and “The West Coast” — and places in-between interviews with musicians Sonny Rollins and Jason Moran, and writers Dan Morgenstern and Robin Givhan. Jazz people will recognize all those names except that of Ms. Givhan, who is a Washington Post fashion critic, brought on board to give her impression of the photographs of audiences taken at jazz venues.

Sittin’ In belongs to the family of large-format jazz-related books like The Jazz Image: Masters of Jazz Photography and Impulse for Change: The Story of Impulse Records. The volume is text-heavier than the former and more graphics-heavy than the latter. Author Jeff Gold breaks the book into sections — “The East Coast,” The Midwest” and “The West Coast” — and places in-between interviews with musicians Sonny Rollins and Jason Moran, and writers Dan Morgenstern and Robin Givhan. Jazz people will recognize all those names except that of Ms. Givhan, who is a Washington Post fashion critic, brought on board to give her impression of the photographs of audiences taken at jazz venues.

Gold writes brief introductions covering the jazz topography of the cities in the volume as well as short descriptions of the venues. His choice of the latter seems to have been based on the ephemera in his own collection. New York City receives the preponderance of coverage — about 100 pages. Chicago gets about 20, and it decreases from there. The only Boston places he includes are Symphony Hall, the Hi-Hat, and North Adams Armory. When I undertook to simply list the number of venues in Boston over the decades there were over a hundred. It’s hard to imagine any book being totally inclusive, but let’s just say that for the sake of organization and honest presentation Gold might as well have put “New York” and “Everywhere Else (afterthoughts).”

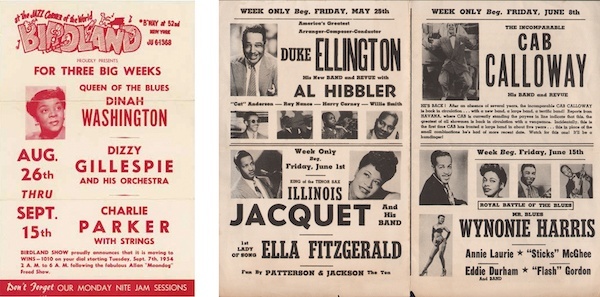

Much of the ephemera — programs, posters, menus, and the like — is pretty interesting. Anyone who thinks that hype is a new invention will be disabused of that idea when they look at this material’s head-spinning claims and grabby graphics. As is to be expected, much of the advertising is sexist (overtly) and racist (less overtly). It’s intriguing to read about how the spaces that these venues occupied were constantly repurposed. The Hickory House went from car showroom to restaurant to nightclub. Central Plaza was first a kosher catering house, then a spot for jam sessions, weddings, bar mitzvahs, television filming, and finally the first home of the NYU School of the Arts.

It’s also informative to see the publicity, menus, etc., from local, non–New York City jazz venues where some of the people who eventually rose to the highest ranks of jazz first learned their trade: for example, Bill Hardman at the Mirror Show Bar in Cleveland, Dorothy Ashby at the Wal-Ha Room in Detroit, and Johnny Hartman at the El Grotto in Chicago.

The life span of most of these places was short, and the book reminds us that this was often the result of challenges that had nothing to do with the relative popularity of the music. There was the influence of “Racial Covenants” — agreements to exclude black people from housing — which led to self-contained black neighborhoods. The practice was banned by the Supreme Court in 1948, but the results of the change were mixed, at best, for jazz venues. There was also the 1944 Cabaret tax imposed in New York City, which added 30 percent to the price of live music. Clubs that allowed no dancing were exempt from the tax, a prime reason that one form of jazz, bebop, became a mainstay in clubs and older forms of the music, intended for dancing, were phased out.

Duke Ellington sitting with fans in the ’40s. Photo: courtesy of the author.

The other graphic components here are photos originally taken by photographers who had been hired to take shots of the audience. These were offered as keepsakes for a buck or two to remember a night out on the town. A lot of authorial text and interview reflections are given over to an evaluation of these photos. Rollins and Moran both talk about the crucial role of the audience in the musical experience and, by extension, the importance of the photos. I agree about the importance of the artist-audience relationship, but I’m not sure this kind of documentation sustains the importance Gold wants to vest in it.

I’ll return to the photographs, but first let me note that the main agenda the author puts forward in this book is that the world of jazz was far ahead of the rest of American culture in terms of racial mixing. Gold occasionally talks about ugly incidents, but his goal is to show the degree to which integration in these places — especially on 52nd St. in New York — was ahead of its time. I partially agree with this assertion. Jazz musicians did interracial jamming and recording as early as the ’20s. But jazz musicians accepted each other because they were fellow members of a hard-won meritocracy and this sense of community, to some degree, flattened out the racial disparities.

When Gold tries to extend this notion of racial comity into the venues and audiences, he’s on shakier ground. The author is ebullient about what’s happening in the photos — couples in love, adoring looks at the musicians, stylish posing, etc. Fashion writer Givhan has a subtler grasp of the content of these photos. In her interview she constantly brings Gold down to earth. For example, when he talks about how much he loves all the black men wearing hats in a photo, she responds: “It plays on a sense of anonymity, to some degree. It’s a uniform and there’s probably a certain degree of safety and camouflage in that.… I suspect there’s probably an element of protection in dressing with the crowd, not standing out.… It’s the whole notion of welcoming the black musicians but not regular black folks in its audience — it’s the notion of being willing to embrace the exceptional but not the average.” Gold assumes a level of ease among the audience in these mixed race environments but, as Givhan observes, while a musician might feel that ease, one can’t assume that a black audience member will.

Birdland and Apollo handbills. Photo: courtesy of the author.

Quincy Jones’s interview is fairly glib and all about the racial upside of jazz. Rollins insists that jazz musicians don’t get enough credit for “breaking down racial barriers.” Moran is thoughtful and analytic; he has a lot to say about audiences, albeit through a somewhat theoretical filter. Dan Morgenstern’s interview deals with his personal experience of jazz and, with caveats, he agrees with Gold’s integration slant. For me, Givhan’s interview is the most perceptive, to some degree because she’s a jazz outsider, responding in the present to photos from the past. She seems to have few preconceptions about what she is supposed to see.

Oral histories suggest that jazz musicians have related to each other with more ease than can be found in other parts of the culture. At the same time, there’s no doubt that venues in general were hostile to racial mixing. So the degree to which jazz — the music and the business — contributed to a progressive model of race relations is an open question, one that generates many different opinions. The essential value of Sittin’ In is its generous collection of memorabilia, but there’s no reason why a book like this can’t look more deeply into substantive issues.The vision of jazz clubs that Gold presents here is not necessarily wrong, but it is fairly glib. His authorial voice, as it emerges in the text and in the interviews, indicates that he is more a “booster” than a scholar. Along those lines, a table of contents and index would have been helpful. Still, the book raises fascinating issues and its wealth of ephemera provides an amusing context in which to ponder deeper questions.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Good review. Like you, I would find the lack of depth about Boston area nightspots a glaring omission. In fact, this’ll be a deal breaker for me, and I doubt I’ll read the book. You write: When I undertook to simply list the number of venues in Boston over the decades there were over a 100. It’s hard to imagine any book being totally inclusive, but let’s just say that for the sake of organization and honest presentation Gold might as well have put “New York” and “Everywhere Else (afterthoughts).”

I’d also like to have seen some mention of the scene in Lowell, MA, where Billie Holiday had her last (or one of her last) club dates before she died.

Thanks, David. Even more egregiously, Philadelphia was completely shut out.

Hi Steven, Jeff Gold, the author here. Everyone is of course entitled to their own opinion. Suffice to say Quincy Jones, my first interviewee, was the person who first told me these clubs were an important place racism began to break down, and racism would have been over in the 50s if people had paid attention to jazz musicians. This surprised me, so I asked the other interviewees about their experiences, and printed what they told me. Sonny Rollins went on a tear about it and told me Jazz musicians “never get credit for this”, “I hope you put this in your book” and “this is a story that needs to be told “. Quincy, Sonny and Dan Morgenstern were all there, and I was eager to hear their eyewitness accounts. Exploring race wasn’t my initial premise, but hearing about from people who were in these clubs at the time, I wanted to explore it. You and I weren’t there, nor were Robin Givhan or Jason Moran—but we have the rare opportunity to hear from these three legends who were. I’m grateful for that. My intention was to explore these clubs from many different angles-musicians who played these clubs, an audience member and later respected historian (Dan), a younger musician who’s work is deeply informed by those times (Jason) and someone good at teasing meaning from photographs (Robin).

As to what I included, I was entirely limited by what I could find from these clubs. This material is very rare. The Boston section has what I could find from Boston. Simple as that. There is a fine comprehensive site on jazz in Boston I credit in my end notes. I did not “shut out” Philadelphia. I simply couldn’t find any memorabilia or souvenir photos from there. I reached out to a Philly jazz critic and some institutions he recommended and came up empty. I agree, it’s a conspicuous absence, but as I say in my intro this isn’t meant to be encyclopedic, nor an academic study. It’s a celebration.

And FYI there is a table of contents.

Jeff-Thanks for reading. A few things: I don’t think I mischaracterize what your interviewees say. In my review I actually use the same quote from Rollins that you cite. Second, I note that “It’s hard to imagine any book being totally inclusive…” but, I think that to justify the geographical divisions you use in the book there should be more ephemera from other cities. I know such exists for the Boston area. Third, yes, there is a table of contents, but it only lists the eleven cities covered in the book. To me, a listing of the many venues would be more useful.

Yes, Philly!! Holy Smokes, that doesn’t say much for the book. Have the author contact me, if he ever does another addition.

What about Detroit?

Like Boston, Detroit gets 3 listings.

A note on the cabaret tax. It was a federal tax, not a local one, and the rate was quickly lowered from 30 percent to 20. That put it on par with other entertainments — moviehouses, for instance. (It was reduced to 10 percent in 1960 and finally abolished in 1965.) Even though it was business-killing tax, I think there was a long list of reasons why dance bands and social dancing declined while small groups developed. There was a giant shift in popular taste in the immediate post-war period. And the creative musicians looking to play jazz abandoned dance band culture in droves for the musical challenges of bebop or jump blues or small-group swing. And there were ways around the tax burden while still allowing people to dance. For one, stop selling liquor. No drinks, no tax. The dance halls hereabouts that never sold liquor (the Totem Pole, the King Philip) were still going into the 1960s. They were doomed by then, for sure, but it wasn’t the tax that doomed them.

I think the author’s point makes sense: if there is no memorabilia for certain clubs in cmcertain citues, then it woukd be hard to include those clubs in a book that is so heavy on visuals and graphics. I also think his point about the book being a celebration, rather than an encyclopedia is a valid one. I think is it a fascinating and impressive book.