Jazz Review/Interview: Duncan Heining Revises His Landmark Biography of Jazz Composer George Russell

By Steve Elman

This is a necessary purchase for those familiar with George Russell’s work, whether to replace the previous edition or to put where the previous version should have been.

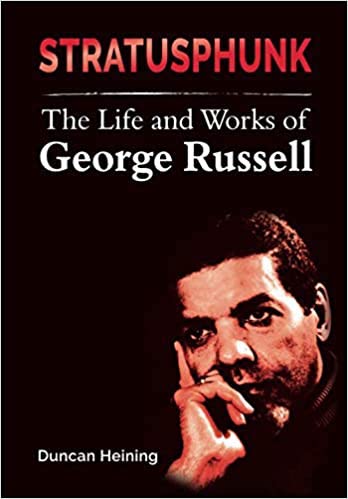

Stratusphunk: George Russell, His Life and Music by Duncan Heining. Jazz Internationale, 371 pages, $19.39.

“I’m never going to conform.” – George Russell, 1997

Death draws a line. The deceased’s work is fixed in time. But the story of a life is different. No matter how assiduous the biographer, the tale he or she undertakes to tell will always be incomplete.

Speaking from personal experience (I co-wrote Burning Up the Air, a biography of Jerry Williams, one of the pioneers of talk radio), no sooner are the proofs of the final pages of a biography sent to the printer than the author begins to ponder how he or she could have done better. And so, Duncan Heining, author of George Russell: The Story of an American Composer (Scarecrow, 2010) has returned, a decade after writing what was the definitive study (Arts Fuse review) of one of the great masters of jazz composition, to look again at his subject – and the result is a book that is significantly rethought, so much so that Heining gave it a new title.

Heining is not just an articulate writer. He is a cogent thinker who speaks with the authority of someone who has given long hours of consideration to a topic. I was very pleased to be able to converse with him recently (by Zoom, from his home in Suffolk, UK) so that I could include here some of his own observations about the evolution of his thinking and the subject of his work.

It is time for this revised book, 11 years after George Russell’s death and 12 years after his last public performance. In fact, it is high time, because the jazz community now has a teeming crowd of ambitious composers, and we need to be reminded that it was not always so. And more than that: we also need to be reminded that the very idea of “jazz composition” was once controversial, and the struggle for this great composer-theorist to achieve respect and honor was never easy. And even more still: a generation of jazz listeners has now grown up without George Russell, and they need to be reminded that even if he is gone, his music is very much alive.

I’ll get to the ways this book is different from its predecessor, but first, we have to deal with the grim reality that George Russell’s name and greatness are fading from the forefront of music.

This is not his fate alone. Ellington and Monk are the only great jazz composers whose work continues to be explored consistently. Monk is lucky in that his masterpieces are small enough to be revisited without much effort – although mastering them is the work of a lifetime. Ellington’s songbook should keep his name alive forever, although his extended pieces regrettably receive even less attention today than they did during his lifetime. But anyone playing Jelly Roll Morton today (thank you, Anthony Coleman) is seen as visiting the swampy Jurassic Park of jazz. And it is truly shocking to realize that so little attention is being paid in our time to the work of Charles Mingus, with the exception of his well-worn tunes like “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.”

Like the work of these masters, George Russell’s music ought to be part of any reasonable jazz library. His great pieces deserve and reward many hearings. And any person who loves jazz and doesn’t know George Russell has a serious deaf spot.

Perhaps a listener vaguely familiar with the name might ask: is there really room in my head for the work of someone I know only by reputation? I can only reply: you don’t know how much room there is in your head. George Russell’s music is so distinctive and powerful that it could be said to express the very idea of Possibility. Coming to know even one of his great works is like discovering that a whole new planet of music exists in your personal solar system. It opens doors of perception you didn’t know you had.

So, to know why he is so important, I advise going to the music first, and then engaging with this biography.

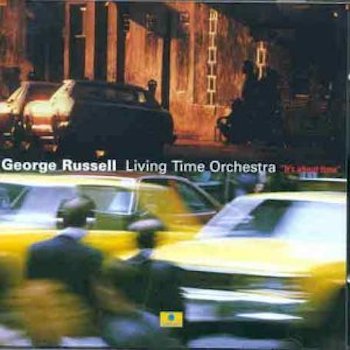

Where should you start? Heining and I discussed what each of us considered Russell’s most important works, and after considering our mutual impressions, I suggest that a new listener begin with part 2 of “It’s About Time” (1995), written for his wife Alice. (For online links and further information about the music mentioned here, see More below.)

In discussing it, Heining said, “I like the pun of ‘It’s about time I wrote something for Alice,’ and ‘about time’ – all of his music is about time.”

Heining meant “time” in all its senses – musical tempo, the times we live in, the passage of time, even time as Einstein saw it – one of the relative essentials, like mass, energy, and gravity.

“It’s About Time” has some of Russell’s most immediately approachable music – heartfelt melody, soaring solos, immense weight, and some of his shiniest trademark funk. None of these elements are assembled as you might expect; in fact, you have to give a full 10 minutes of concentration here to hear it fully, because Russell’s mature works avoid traditional ideas of beginning, middle, and end, and reveal their overall picture only in the last seconds of hearing. It’s worth noting, however, that this composition uses one of the oldest tricks of jazz, guaranteed to wow an audience – the “one more time” reprise that will always be associated with Count Basie, thanks to his recording of “April in Paris.” As you’ll hear, Russell has fun with the idea in a very Russellian way.

Once you’ve heard part 2, you’ll want to go back and hear the work in its entirety. And there is much more Russell for you to appreciate.

The new listener might soon say: Who is the man who could write such distinctive music? What forces shaped him and his thinking? How did he write? And some listeners will surely ask: why haven’t I heard more about him?

All of these questions are answered in great detail and with admirable style by Duncan Heining. If you know George Russell’s work, Heining’s revised biography is a necessary purchase, whether to replace the previous version on your shelf or to fill the spot where the previous version should have been. If you do not know his work, Heining will enlighten you and bring you closer to one of the geniuses of American music.

There are qualities that distinguish Russell’s music from the very first things he wrote. You can hear them in “Cubano Be, Cubano Bop” (1947), a piece he wrote for Dizzy Gillespie’s big band, and you can hear them in “It’s About Time,” from 48 years later.

I hear his gift for melody – no matter how complex the work or how intricately interwoven the musical lines, Russell knows how to make his themes sing. And I always recognize the voice at the bottom – Russell’s parts for bass are never support for support’s sake, never just notes to hold things together; they sing differently.

Heining hears more:

[He has] certain “signatures,” like the use of percussionists conversing – in “The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature,” where percussion lines in the tape material [accompany a live drummer], the bata percussionists in “The African Game” [alongside a trap drummer], the drummers in “Fellow Delegates” – Paul Motian, Osie Johnson, and Russell himself playing boobams – these are like a composer’s signature. Another [quality] is the way he uses instruments for their rhythmic potential. He doesn’t just ask the saxes or brass to play the melodies. They have a whole series of roles, [emphasizing] the way the rhythms are stacked. [And] there’s so much information – different time sequences, different tonal centers – it should be a mess, but it’s not. Russell’s music has complexity whilst at the same it’s accessible. It has electricity.

Russell considered his compositions to be personal expressions of his theoretical work – embodied in a seminal text called The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, first published in 1953 and reexplored through the rest of his life.

Knowing about “The Concept,” as its students abbreviate it, is not necessary for an immediate appreciation for Russell’s music, but Heining notes:

Theory shouldn’t frighten us.

It doesn’t, as some jazz fans and even musicians seem to think, take away the magic. The Concept is like a map, but it’s a map of possibilities. For me, the more I know [about it] the more I understand, not just intellectually but emotionally as well.

What George was talking about [in The Concept] was a way that improvisers could negotiate a piece of music – [staying] close to a tonal center, [moving] away from it, but always knowing where they are [in relation to it]. That seems to me to be immensely practical.

The Concept is a way of looking at music as an organized system. And as a social scientist interested in systems, I can say clearly that it has both an elegance to it and it is internally coherent and consistent. A lot of people go on about the jargon [George uses], but something in the way that George describes it – that issue of language – is quite important. If you’re genuinely saying something new, you may need a new language to describe it.

“The Lydian Chromatic Concept [of Tonal Organization]” – can you think of a better description [than the one George invented]? It’s based on the Lydian mode. It recognizes the fundamental importance of the chromatic scale. It’s concerned with the way that tones can be reorganized in musical space. It does what it says “on the can” [that is, “as advertised”].

All well and good, you might say – but what IS The Concept? Without a course in music theory, how can an untrained listener get a handle on what Russell offered?

In the fewest words I can compose, it is a way of liberating musicians from the prison of tonality that has been the core structure of Western music theory, and of showing how a musical space can be constructed to allow any note to sound “right.”

How can you hear The Concept in action? Go to the best-known of all jazz recordings, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue.

Listen to the first 30 seconds of “Blue in Green.” Try to hear it as if you were hearing it for the first time. Bill Evans’s piano chords establish a mood – but what kind of a mood is it? Meditative, melancholy, wistful, yearning, spiritual? It is all of these things. By choosing a progression of chords that were inspired by Russell’s Concept, Evans was able to suggest a complexity of emotion that was beyond the capabilities of popular song up to that moment.

And then Davis begins. His first few trumpet notes don’t emphasize any of the chords heard so far. But they make perfect sense to the ear nonetheless – and they add yet another layer of emotion.

The rest of the track is an ingenious display of what the featured players do with the framework suggested by Evans in the introduction. Each soloist – Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley – is free to move from one harmonic emphasis to the next as discursively or as briefly as he likes without relying on the traditional framework of chords and choruses.

Davis and Evans readily admitted Russell’s importance to Kind of Blue, and Davis used The Concept, consciously and intuitively, in all the music he made through the rest of his life.

The Concept blew open many doors that musicians had assumed were locked shut. The most prominent example is how it fostered modal improvisation, which was essential to John Coltrane’s mature music and to that of the dozens who followed his path.

Russell admired how others used The Concept, but he emphasized that each musician ought to use it to find a place where he or she could best be themselves.

His own music presented a far more ambitious display of its possibilities than any other artist has offered to date.

In addition to “It’s About Time,” Heining identified five other works that he considered “most important” among Russell’s many, and he deals with each of them in depth in his book. The range of these pieces, simply considering how each strikes the ear on first hearing, testifies to the enormous variety The Concept offers. I have rearranged them here in the order of their approachability for the new listener:

- New York, N.Y. (1958). An LP-long suite of pieces, including radical transformations of three standards – “Manhattan,” “Autumn in New York,” and “How About You,” framed by Jon Hendricks’s timeless jazz poetry, featuring a landmark tenor sax solo by John Coltrane on “Manhattan” and remarkable drumming from Max Roach on “A Helluva Town.” Much of this session has a modern-big-band quality, transformed by The Concept.

- The African Game (1983). Another LP-long work. This LP captured the premiere performance in Emmanuel Church in Boston, recorded vividly and produced by Russell to get the balances he wanted. It was a life-changing experience for all who were there, yours truly included. The instrumentation is that of a conventional big band, plus an ensemble of bata drummers, but its use of electronics, sound effects, and unconventional orchestration make it anything but typical.

This work may be heard as pure music – and it is great if listened to in that way – but Heining cites the program Russell invented for it as significant to his understanding:

[This] was the record that sealed it for me. [It is] a reflection of how humanity had developed from its origins, and how it had responded to the development of societies and technology. It’s one of the few [works] in jazz that bears comparison with the deep spirituality of Olivier Messiaen – it has that profundity.

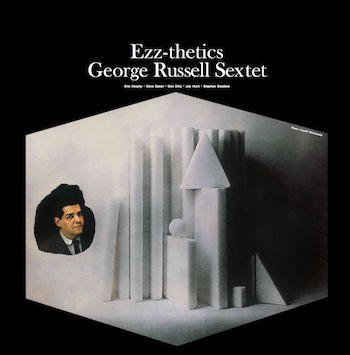

- The Ezz-thetics session (released on Riverside in 1961 and reissued in many forms since) features Russell’s dramatic rearrangement of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight,” conceived of as a feature for Eric Dolphy, who makes it immortal. This performance begins and ends with a sound-picture of the city at midnight, with George’s “conventional” sextet of the time (trumpet, saxophone, trombone, piano, bass, and drums) going to places beyond their usual note-making to open up the acoustic space.

- “The Day John Brown Was Hanged” (1956). A seven-minute programmatic piece from a session led by saxophonist Hal McKusick that is Russell’s most direct commentary on the history of racial injustice in the US. This is an example of what might be called “chamber jazz” – a quartet of alto saxophone, guitar, bass, and drums with detailed prewritten material throughout and a progression of four movements. It doesn’t sound anything like the typical jazz quartet.

- “The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature” (1968) from The Essence of George Russell. This is the large-ensemble version of the piece, one of the first that Russell chose to divide into nonlinear “events.” It incorporates taped and synthesized elements into a live performance that includes extended improvisation sections. This version features Scandinavian musicians Russell fostered during his years in Norway, many of whom went on to distinguished careers in their own rights – Jan Garbarek, Terje Rypdal, Arild Andersen, and Jon Christensen – plus trumpeter Stanton Davis, who was a Boston stalwart during the 70s.

In mentally and aurally reviewing these works I have come to know so well, I was struck by how magnificently they have transcended their times. In his book, Heining notes contemporary critical reactions to many of them, from the scoffing at Hendricks’s hip poetry in New York, N.Y. (which now seems so wise and witty) to the puzzlement at the use of tape in a jazz context in “Electronic Sonata” (which now lives as a logical and necessary part of the music), to the denigration of the funk parts in The African Game (and, for that matter, in the earlier Living Time) as “big band rock and roll” (which now read as necessary foundations for Russell’s most ambitious constructions).

Now that you know why you should hear Russell, you probably want to know how Heining’s new edition of the composer’s biography is different from the previous one.

There is a new title, beginning with the name of one of Russell’s frequently covered tunes, an invented word that also nicely describes one of the most appealing aspects of his music – Stratusphunk: George Russell, His Life and Music. Heining explains:

“In the first version, George Russell: The Story of an American Composer, I wanted to work against the tendency to see African-American composers as composers in their own category, not sharing the same status as Copland, Varese, Ives, Bernstein, Reich, or Adams. But when you still have a struggle for recognition going on, you still have to talk about all those distinctions – Black, White, Women, Gay … recognizing these distinctions and citing the individual contributions in ways that acknowledges difference. By the time of this edition, my thinking had moved on. The book [now] reflects a different understanding. Yes, George might have been an American, but he was and saw himself first as an African-American composer. The book needed to reflect that more clearly.”

“In the first version, George Russell: The Story of an American Composer, I wanted to work against the tendency to see African-American composers as composers in their own category, not sharing the same status as Copland, Varese, Ives, Bernstein, Reich, or Adams. But when you still have a struggle for recognition going on, you still have to talk about all those distinctions – Black, White, Women, Gay … recognizing these distinctions and citing the individual contributions in ways that acknowledges difference. By the time of this edition, my thinking had moved on. The book [now] reflects a different understanding. Yes, George might have been an American, but he was and saw himself first as an African-American composer. The book needed to reflect that more clearly.”

Another important change is the tone of much of the writing about racial justice:

“I was beginning to rethink some of my own ideas about how one would write about jazz and what the cultural imperatives might be. At the time I wrote [the first version], my primary sense of Russell’s experiences with racism growing up in Cincinnati was that [those experiences] were lamentable historical events. Now they seem very present. In 2010, although we might have been a long way from the promised land of Dr. King, the USA had an African-American president, and it seemed that many of the basic arguments about racial justice had been won. We seemed to be moving forward socially, politically, culturally. But now we are seeing the rise of the far right, not just in America but internationally, and there is a sense that we are having to fight the battles again that we thought were part of our past experience. When I got the rights to my book [from the first publisher], I realized that there will always be a new way of telling the story.”

There is an extensive new introduction, with many important observations colored by Heining’s deepened familiarity with Russell’s music.

The chapter in which The Concept is introduced (“New York, N.Y. or in Search of the Lost Chord”) has been reworked for greater clarity.

The second two-thirds of the book have been restructured usefully – what were five chapters and an afterword have become nine, allowing the reader to separate the events in Russell’s life more logically. The new chapter titles include a Monty Python pun (Chapter 9 is called “Norwegian Blues – Pining for the Fjords?”) and words that should gladden hearts in Beantown (Chapter 11 is called “Living Time at New England Conservatory”).

The final chapter, a philosophical summation called “On Conceptual Thinking,” has been almost completely rewritten and is much improved.

“I wasn’t happy with the last chapter. Two reviewers described it as “arid and convoluted.” I couldn’t disagree, and thought at the time that if opportunity arose, I would want to rewrite that chapter. It also happened that between the two editions I decided that I would study music theory formally. So, when it came to this edition, I felt much better prepared to deal with issues regarding George’s Lydian Concept.”

Finally, speaking practically, Heining, noted, “The new [paperback] version is cheaper [than the original hardback] – more bang for your buck.”

I think the revisions are great improvements.

Of course, a reviewer is expected to quibble, and I have to note that the book still does not have an appendix with a complete chronological list of Russell compositions and arrangements, which would round out the admirable appendices of his recordings and his tour dates. There is an alphabetical list of most of his compositions, which can be found under Russell’s name in the index, but this is not comprehensive, even though that list has been much improved by the layout in the new book.

This is a very small matter. Heining has shouldered a great burden once again, and carried his task to a newly triumphant conclusion. As he told me, “This book and publicizing it is what I can do and have to do for George.”

There are some other issues suggested by the subject of the book that occupy Heining’s thinking and deserve some exposure here.

At the heart of my conversation with him was our mutual concern about ways in which modern perceptions of music are having an impact on the ability of current and future listeners to give the whole universe of art music, including Russell’s, the consideration it deserves.

A generation of jazz listeners has now grown up without George Russell, and they need to be reminded that even if he is gone, his music is very much alive.

“With an LP or CD, you have a physical product or artifact. When I hold a record in my hand, I can visualize that whole chain of production involved in bringing that to me. I have a sense of all the stages leading back to those hours in the studio or on stage when the musicians played the music I’m hearing. It is an embodiment of that moment of musical creation. At some point, I might dispose of it but, even then, I have to think about how to do so – give it to a friend or a charity store, sell it on eBay. With digital recordings, there is only sound [in the form of digital files]. It is both without substance and disembodied. All I need to [do to] dispose of it is press a button. I suspect it changes how one hears the music and values it. It becomes ephemeral, a thing we flit towards like moths to a light.

“I’m reminded of E.M. Forster’s short story, ‘The Machine Stops.’ We’re living in something like the dystopian society he describes. But what happens if all of this machinery were to stop and we’d have to start doing it for ourselves?”

Heining was also profoundly concerned about the growing neglect of musical education, not just in the US, but in his own country and in many others.

“The only way I think jazz can get a foothold [in the minds of people unfamiliar with it] is through early education. When I was in primary school, teachers played us classical music. I came to know a lot of famous pieces, and we also had singing lessons. We sang pieces that came primarily from the English National Songbook put together by Vaughan Williams. We had a bit of musical education. We were exposed to music with complexity. But that doesn’t happen [anymore] in the private schools. But that may happen now in private education but not in state education.

“People aren’t being educated [any longer] to deal with complex music, or complex ideas in literature, or in politics. [But] people can cope with complexity [if they are only given the opportunity].

“If you don’t have the potential of a musically literate population, where are musicians [working in complex forms] going to find their audience?

“The only answer I see is that jazz has to become more of a samizdat music. It has to [marshal] its own kind of organization, [embrace the idea of being] a ‘guerrilla’ music, [fighting for a place within society].”

George Russell fought that fight through his entire life. He deserves a place in your heart and in your mind. Heining’s book will illuminate that fight and inform your understanding of Russell’s towering contributions to art.

MORE:

A thorough examination of Russell’s importance to the Kind of Blue session can be found in Eric Nisenson’s excellent book, The Making of Kind of Blue: Miles Davis and his Masterpiece (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000)

Beyond the compositions spotlighted by Heining, I would also recommend:

- “All About Rosie” (1957), a three-movement piece for small ensemble commissioned by Brandeis University for a Festival of the Creative Arts that featured works integrating jazz and classical elements, which was a radically new idea at the time. It thrillingly sums up Russell’s work to this date and includes a piano solo by Bill Evans before he joined Miles Davis that stunned listeners and launched his mature career. It elaborates on the counterpoint Russell used in “The Day John Brown Was Hanged,” and perfects ideas used in “Concerto for Billy the Kid” (1956), another piece featuring Evans.

- “Living Time” (second version, 1995) is, in a way, the long-delayed follow-up to “All About Rosie,” so different from the earlier piece that it could well be from another universe. It was originally composed in 1972 for an LP under Bill Evans’s leadership, as a kind of jazz piano concerto (though completely different in form from any other work of that genre). It was the first Russell work to appear in America after his long sojourn in Scandinavia, showing the result of his experiments with electronics and his new ideas about form. It also spotlighted some of the most prominent jazz musicians of the time, including breathtaking contributions from tenor saxophonists Joe Henderson and Sam Rivers and drummer Tony Williams. Though the 1972 performance is spectacular, Russell felt that producer Helen Keane’s mix was seriously wrong, so he longed for a chance to put things right. He finally got that chance in 1995, and capped it by adding new parts for strings, which were orchestrated by percussionist Pat Hollenbeck, who became one of Russell’s closest associates in his later years. I’ve discussed this work at length in another Fuse post.

In looking for George Russell’s music on CD and online, you should be aware that there are two other George Russells – the fine Boston-area pianist George W. Russell Jr. (no relation), who is active in both jazz and gospel, and George H. Russell (1919-2008), a composer/guitarist. Works by both of them are regularly and erroneously included in releases attributed to the composer/theorist.

As Heining notes, old-school appreciators of music are still wedded to physical product. If you’re one of them, a goodly number of Russell releases (in their original form as well as in reissue packages) are available as of this writing. However, untangling them is a thorny matter.

- Hal McKusick’s Three Classic Albums (Avid, 2015) is a reissue package by an underrated saxophonist that contains the first recordings of a number of early Russell compositions – “The Day John Brown Was Hanged,” “Lydian Lullaby,” “Miss Clara,” and “Stratusphunk.” It also contains the first recordings of Gil Evans’s “Blues for Pablo” and “Jambangle.”

- Russell’s The Complete Albums Collection 1956-1964 (Chrome Dreams, 2015) is probably the pick of the currently available reissues. It puts 10 of Russell’s early LPs on three CDs at a bargain price (about $2 per LP), including the indispensable New York, NY and Ezz-thetics. Also included here are Russell’s arrangement of “You Are My Sunshine,” which includes an unforgettable vocal solo by Sheila Jordan, and five early compositions by Carla Bley, a composer Russell championed from the very beginning. Despite the “Complete” in the title, it does not include “All About Rosie” or “The Day John Brown Was Hanged,” both from the same period.

- An alternative to the Chrome Dreams reissue, though less comprehensive and more expensive, is a two-CD set called Complete 1956-1960 Smalltet and Orchestra Recordings (Fresh Sound, 2014) This includes “All About Rosie” and “New York, NY,” but does not include the Ezz-thetics session or “The Day John Brown Was Hanged.”

- If you opt for the Fresh Sound set, you could supplement it with Seven Classic Albums (Real Gone Jazz, 2013), which duplicates “New York, NY” and includes the Ezz-thetics session, plus The Outer View, which includes “You Are My Sunshine.”

- Ezz-thetics is still available by itself, both in CD form (Riverside, 2007) and 180-gram vinyl (Jazz Workshop, 2018).

- Complete Recordings on Black Saint and Soul Note (Black Saint / Soul Note, 2011) is an expensive set, reissuing material from 1968 to 1983, including eight single LPs and the two-LP set The Essence of George Russell. It offers three versions of “The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature,” including the one recommended by Heining, and three notable long works which are not currently available in any other form – “Othello Ballet Suite,” “Vertical Form VI,” and “Time Spiral.”

- The Essence of George Russell (Soul Note, 2010) is also still available by itself in CD form. It contains the large-ensemble version of “The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature” recommended by Heining.

- The CD reissue of The African Game (EMI / Blue Note) is still available, preserving the striking original cover art.

- It is unfortunate that the best of Russell’s last recordings, It’s About Time (Label Bleu,1996), is only purchasable as a digital download from Amazon. It not only includes the only full recording of the title composition, which Heining and I recommend, but Russell’s final realization of “Living Time.”

George Russell online:

Nearly all of the recommended works above are hearable online, though you may have to do some searching.

- Part 2 of “It’s About Time” (1995), from its first recording, is hearable on Spotify, Deezer and YouTube:

A shortened version of “It’s About Time,” which is more straightforward but less magical, appeared on The 80th Birthday Concert CD (Concept, 2005), which is still available commercially and is hearable on Pandora and Shazam.

- New York, N.Y. (1958) is hearable in its entirety on Spotify. Pandora, Deezer, and KKBOX. The five parts are separately available on Shazam and YouTube. If you use the latter, you should hear them in the original order:

“Manhattan” (Richard Rodgers / Lorenz Hart): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yGof9LU73c

“Big City Blues”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsY2UimdaoY

“Manhatta-Rico”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUnKX1DxR40

“East Side Medley: ‘Autumn in New York’ (Vernon Duke / Ira Gershwin) and ‘How About You’ (Burton Lane / Ralph Freed)”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmKveEPLbu4

“A Helluva Town”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vxow2Um3NzM

- The African Game (1983), in its original 1983 recording, is hearable on Spotify and Deezer (where it is called “Live from Boston, Massachusetts / 1986”). It is not available on YouTube.

However, another great live performance of the work, from The 80th Birthday Concert, recorded 20 years later, is hearable on Shazam, Deezer, Pandora, and YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Wee2HSvClY

- The Ezz-theticssession (1961) is hearable in its entirety on Spotify, KKBOX, Pandora, and Deezer (but the Deezer stream is in monaural only). Russell’s dramatic rearrangement of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight” from this session is hearable by itself on Shazam and YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Wee2HSvClY

- “The Day John Brown Was Hanged” (1956) is hearable on Pandora, Deezer, and KKBOX, but not on Spotify or YouTube

- The large-ensemble version of “The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature” (1968), from The Essence of George Russell (Sonet, 1971), is hearable on Spotify, although the work’s title is not shown on the track listing for the album – it is simply shown as “Parte [sic] 1 – 2 – 3.” It is also hearable on YouTube:

A portion of the large-ensemble version was played in The 80th Birthday Concert, and that excerpt is hearable on Shazam, Deezer, Pandora, and YouTube.

There are two recordings of the small-group version, one in 1968 and one in 1980. The 1968 version is hearable on Spotify, with the title properly shown. It is also hearable on YouTube, divided into the two parts it had on the original LP:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lbFwrfrymw

- “All About Rosie” (1957) is hearable on Spotify, Deezer, KKBOX, Shazam, and YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Z7X83Nijbk

- “Living Time” (second version, 1995) is available on Spotify and Deezer, although in both cases, you must access the It’s About Time LP, and the title of the work is not shown; instead, you will see individual track listings – “Events I – VIII.”

- The first version of “Living Time,” with Bill Evans, is hearable on Spotify as well, and on YouTube:

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: George Russell, Jazz Internationale, Steve Elman, Stratusphunk

What George was talking about [in The Concept] was a way that improvisers could negotiate a piece of music – [staying] close to a tonal center, [moving] away from it, but always knowing where they are [in relation to it]. That seems to me to be immensely practical.

What George was talking about [in The Concept] was a way that improvisers could negotiate a piece of music – [staying] close to a tonal center, [moving] away from it, but always knowing where they are [in relation to it]. That seems to me to be immensely practical.

Thank you for writing this definitive piece. It is and will remain a valuable resource for anyone who would explore Russell’s career.

I agree — proud to post such a thoughtful and informative piece that pays homage to such an important (and underappreciated) jazz artist.

Outstanding work. Thank you, Steve!