Jazz Survey: Chordless Drills – A Listener’s Guide to the Saxophone Trio

By Steve Elman

Here is a personal selection of recordings in the saxophone trio format. These linear collaborations have been part of the jazz scene for at least 70 years now. The results are almost always illuminating and exhilarating, and a review of them offers a miniature history of saxophone styles.

The new Bruno Råberg recording, with Allan Chase on saxophones and Austin McMahon on drums (see separate Fuse post), sent me for a long aural journey along one of the most venerable side-paths in jazz – the saxophone trio. When there is no piano, guitar, organ, vibraphone or other chordal instrument to feed harmonies to the ensemble, and no other soloist to share the front line, the players have to rely on each other even more than they do in a “normal” ensemble. Flaws are more naked; if you make a mistake, you have to find a way to make it sound like you intended the mistake all along.

These linear collaborations have been part of the jazz scene for at least 70 years now. The results are almost always illuminating and exhilarating, and a review of them offers a miniature history of saxophone styles.

The format, championed by Sonny Rollins in a couple of landmark recordings from 1957, is relatively unusual until the mid-1960s, when Ornette Coleman decided that pianists got in the way of his harmonic adventures. The avant-garde then seized the medium by the throat. We didn’t get a significant return to straight-time performances of traditional repertoire in the sax trio until Joe Henderson’s State of the Tenor in 1985. After that, it seems that jazzpeople came to consider the format to be useful across the whole spectrum of styles, which leads us nicely to Råberg’s recent recording, a date that runs the gamut from straight time to free improv.

Here is a personal selection of recordings in this trio format. You could do worse in these times of live-music deprivation than to spend some time with these performances; their intimacy is particularly rewarding because the interplay doesn’t need the dimension of sight for a full appreciation of their riches.

By the way, “chordless” is just shorthand for what’s going on here. JD Allen chastened me in advance about using that term when he was talking about the trio format to Stephanie Janes on “The Jazz Gallery” website.

If you think “chordless,” then you won’t address the chords: “Oh, there’s no chords, so I’m not gonna address it.” When I met Ornette Coleman, he had chords. He was talking about changes [even though he didn’t use a piano] . . . chordless is just not [accurate].

The 28 recordings here are in chronological order by date of recording. I’ve identified the reed instruments being played, but for the most part, I’ve shown the names of the bassists and drummers without instrumentation, bassist first, except for the few dates where the bassist or drummer is the leader.

Don Byas (ts) & Slam Stewart (b, vo, foot taps): “Indiana” (James F. Hanley / Ballard MacDonald) (originally Commodore 78 rpm single, 1945; LP issue on Town Hall Jazz Concert 1945, Atlantic, 1973; not reissued on CD, but hearable via YouTube) This performance (along with an equally stunning “I Got Rhythm” from the same live concert) stands as one of the earliest recordings, if not THE earliest one, of a saxophonist improvising without the support of a chordal instrument. There is no drummer, but Stewart is such a firm timekeeper that a drummer would be superfluous anyway, and the bassist’s foot taps provide a bit of percussion for those who need it. After a tiny intro from Stewart, Byas sets a furious pace that never lets up, anchored in the mainstream, roaring along like a 12-cylinder Duesenberg, but also feinting at changing the key and anticipating Coltrane’s sheets-of-sound with substitute chords. After Stewart almost steals the show with his characteristic wordless singing accompanying an arco solo, Byas comes back with an even more stunning second solo. This performance set a jaw-dropping standard that still is hard to beat.

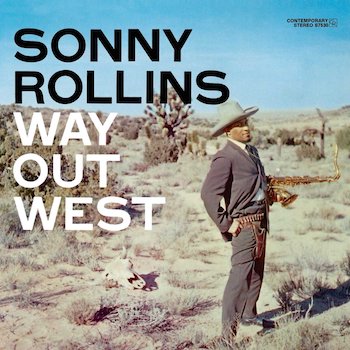

Sonny Rollins (ts): Way Out West, w. Ray Brown, Shelly Manne (Contemporary, 1957; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Come, Gone” (Rollins; contrafact of “After You’ve Gone” [Turner Layton / Henry Creamer]). Even though Rollins’s November 1957 Village Vanguard trios are justly celebrated as some of the great sax trio recordings of all time (see “More to explore” below), the execrable dead-fish-on-newspaper sound of the drums in the Vanguard numbers has always made them tough going for me. This earlier session (from March 1957) is historic — one of the first sax trio recordings of the modern era — filled with great camaraderie among the players, and beautifully recorded, giving us the chance to really hear Ray Brown’s operatic sound on bass and the sensitive drive of Shelly Manne, one of the smartest drummers ever. “Come, Gone” opens with a fluid solo cadenza, and then Rollins simply romps through the tune, sometimes evoking the great saxophonists of the past but more often just showing his own complete mastery of thought and technique. His solo ends with some furious arpeggios, and then he simply stops. Brown walks on as if nothing has happened, and you realize that they have slipped into the bass and drum features. The joke goes on: Brown stops his walk suddenly, leaving Manne to improvise a drum break before Brown’s “official” solo begins. After Manne has his tasteful say, the saxophone is back for a final chorus and a schmalzy ending, both sincere and sardonic at the same time, a feat that only Rollins seems able to achieve.

Sonny Rollins (ts): Way Out West, w. Ray Brown, Shelly Manne (Contemporary, 1957; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Come, Gone” (Rollins; contrafact of “After You’ve Gone” [Turner Layton / Henry Creamer]). Even though Rollins’s November 1957 Village Vanguard trios are justly celebrated as some of the great sax trio recordings of all time (see “More to explore” below), the execrable dead-fish-on-newspaper sound of the drums in the Vanguard numbers has always made them tough going for me. This earlier session (from March 1957) is historic — one of the first sax trio recordings of the modern era — filled with great camaraderie among the players, and beautifully recorded, giving us the chance to really hear Ray Brown’s operatic sound on bass and the sensitive drive of Shelly Manne, one of the smartest drummers ever. “Come, Gone” opens with a fluid solo cadenza, and then Rollins simply romps through the tune, sometimes evoking the great saxophonists of the past but more often just showing his own complete mastery of thought and technique. His solo ends with some furious arpeggios, and then he simply stops. Brown walks on as if nothing has happened, and you realize that they have slipped into the bass and drum features. The joke goes on: Brown stops his walk suddenly, leaving Manne to improvise a drum break before Brown’s “official” solo begins. After Manne has his tasteful say, the saxophone is back for a final chorus and a schmalzy ending, both sincere and sardonic at the same time, a feat that only Rollins seems able to achieve.

John Coltrane (ts): w. Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones; “Blues to You” (Coltrane) from Coltrane Plays the Blues (Atlantic, 1960). Only two tunes from this session were recorded without McCoy Tyner’s piano, but they are among the most interesting pieces from this phase of Coltrane’s career. “Blues to You” puts Coltrane’s tenor in the spotlight, and thus invites comparison with Sonny Rollins’s “Blessing in Disguise,” with the same rhythm team, from six years later, and Elvin Jones’s first date as a leader, with Joe Farrell, recorded eight years later (see below for both). Coltrane is superbly fluid throughout, and the lack of piano comping gives the performance a purity that is almost austere. The blues as a form has long been a context in which soloists could play “against the changes” with impunity, since “wrong notes” could be resolved fairly easily. Here Coltrane moves whole chords (using his arpeggiated “sheets of sound”) against the changes, but resolves them without a hint of dissonance. He and Jones are always great together, but this session, with its roots-oriented approach, is especially tasty, with Jones’s behind-the-beat drumming and Coltrane’s behind-the-beat phrasing making even the most adventurous leaps seem relaxed. Other than some short exchanges with Jones, the whole track is taken up with Coltrane, which leaves Garrison to hold things together, and that is done to perfection.

Lee Konitz (as): Motion, w. Sonny Dallas, Elvin Jones (Verve, 1961; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “I Remember April” (Gene DePaul / Patricia Johnson / Don Raye). If a single session can provide a listener with everything important about a great master, this is it. Konitz has rarely been so splendidly recorded or so beautifully showcased as he is here. Since the stereo mix is exactly the same as the mix on the Rollins date above (sax on one side, bass on the other, drums at center), this provides a perfect contrast and comparison. Konitz’s is a naked kind of art, much less extrovert than Coltrane’s or Rollins’s. His thinking is built on Charlie Parker’s innovations, but his phrasing gives you much more room to consider what he is doing. That approach, consistent throughout his career, avoids any excess or grandstanding, and in this date there are no other soloists — or interruptions from the rhythm section — to distract from that elegant linearity. In fact, the sound of the bass and drums on this date is unlike that of any other saxophone trio recording in this survey, because of the shadow of Lennie Tristano, mentor to both Konitz and Dallas, who felt that the ideal rhythm section should be as smooth and unobtrusive as possible. So, Dallas walks, with one note on each beat, throughout each tune, even within his few feature spots, and Jones reins in his flamboyant style a bit. Fortunately, he is still Elvin Jones, and that’s the chief reason this is a genuinely cooperative trio rather than a soloist with a couple of metronomes.

“April” is a tune with strong harmonic shifts, so it provides a great entry-point for someone who doesn’t know Konitz’s work. A short drum intro leads right into Konitz’s improvisation, which barely hints at the actual theme of the tune. It’s almost like a conversation with himself, a stream of terse musical observations and tension-building pauses that give the listener opportunities to admire the last phrase while Konitz is considering the next one to play. At about 5:45, he stops for what seems like an uncharacteristically long pause, but this is a joke on the listener, because he has actually begun a series of eight-bar exchanges with the rhythm section. Dallas and Jones continue to churn along in their eights just they have previously, with only the slightest shifts of focus. Konitz takes control again at the start of the next chorus, playing against the chords briefly as if to say, “Pay attention now.” Only in the final A section does he get close to the melody, and this is as much a cue to the section that he is finished as much as it is a satisfying ending.

Steven Cerra has compiled impressions from Konitz and others about this session, for those who want to know more.

Albert Ayler (ts): Spiritual Unity, w. Gary Peacock, Sunny Murray (ESP-Disk’ LP, 1964; reissued in an “expanded edition” CD, 2014; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Ghosts” (Ayler) – Second Variation. What once was incomprehensible to the average jazz listener has now become almost classic, and what seemed in 1964 (just three years after Konitz’s Motion) to be an impenetrable jumble of noise now sounds organized, even spacious. This was Ayler’s first recording, and his approach was initially met with puzzlement and even alarm, as in “What is jazz coming to?” Only later did some perceptive listeners connect the saxophonist’s braying tone with the kind of music made in Black churches, where saxophonists were known to play ecstatically, “speaking in tongues” through their instruments. Now that we know of Ayler’s own roots in church, blues, and R&B, his approach seems logical, if iconoclastic. The theme of “Ghosts,” like many of his themes, has an elemental quality, like a marching band tune or a Salvation Army hymn or an old folk song. Peacock sounds root notes under this theme without ever establishing tempo, and Murray provides “color percussion,” with an elegant light touch, mostly shimmering cymbals, with some brushwork on the snares. This is the essential approach throughout. When Ayler moves away from the theme, Peacock moves with him but holds his anchoring job, feeding big bottom notes from time to time. Murray also gets busier, but never challenges the saxophone for the lead. Ayler recalls some of the motifs of the tune, but mostly engages in speech-song. It may be instructive to think of his playing as akin to preaching from the pulpit; it has the same exhortative quality, and is less about notes than it is about sounds. Peacock has a short solo, with Murray opening up the percussion to provide space around the bass. Ayler takes a short final solo and then leads back into the theme, playing more and more softly until only Peacock’s bass is left for a final note.

Albert Ayler (ts): Spiritual Unity, w. Gary Peacock, Sunny Murray (ESP-Disk’ LP, 1964; reissued in an “expanded edition” CD, 2014; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Ghosts” (Ayler) – Second Variation. What once was incomprehensible to the average jazz listener has now become almost classic, and what seemed in 1964 (just three years after Konitz’s Motion) to be an impenetrable jumble of noise now sounds organized, even spacious. This was Ayler’s first recording, and his approach was initially met with puzzlement and even alarm, as in “What is jazz coming to?” Only later did some perceptive listeners connect the saxophonist’s braying tone with the kind of music made in Black churches, where saxophonists were known to play ecstatically, “speaking in tongues” through their instruments. Now that we know of Ayler’s own roots in church, blues, and R&B, his approach seems logical, if iconoclastic. The theme of “Ghosts,” like many of his themes, has an elemental quality, like a marching band tune or a Salvation Army hymn or an old folk song. Peacock sounds root notes under this theme without ever establishing tempo, and Murray provides “color percussion,” with an elegant light touch, mostly shimmering cymbals, with some brushwork on the snares. This is the essential approach throughout. When Ayler moves away from the theme, Peacock moves with him but holds his anchoring job, feeding big bottom notes from time to time. Murray also gets busier, but never challenges the saxophone for the lead. Ayler recalls some of the motifs of the tune, but mostly engages in speech-song. It may be instructive to think of his playing as akin to preaching from the pulpit; it has the same exhortative quality, and is less about notes than it is about sounds. Peacock has a short solo, with Murray opening up the percussion to provide space around the bass. Ayler takes a short final solo and then leads back into the theme, playing more and more softly until only Peacock’s bass is left for a final note.

Ornette Coleman (as): At the Golden Circle, Stockholm, w. David Izenzon, Charles Moffett (Blue Note, 1965; originally issued in two LPs; reissued as two CDs with alternate performances of some of the tunes; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Doughnut” (Coleman), from Vol. 1. Almost all of Ornette Coleman’s work was done without chordal instruments, to allow himself and other soloists maximum harmonic flexibility, but this live date is his most expansive recording without another lead horn, until Sound Grammar (see below). Some of the music from the Golden Circle introduced Coleman’s trumpet and violin playing, which even now are acquired tastes, but his alto saxophone work here is superlative, and he never had more interesting support — not that the players here are better than Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins and Eddie Blackwell, who were the vital foundations of his first landmark recording. But David Izenzon was a true wizard on the bass, with amazing arco facility, and Charles Moffett brought more of a “color percussion” sensibility to the drummer’s role than either Higgins or Blackwell. “Doughnut” is a dynamic swinger throughout, with a jaunty theme. Izenzon is as tuned-in to Coleman’s key shifts as Haden was, and he provides a driving pulse for the leader. Moffett never loses the beat, but he plays all around it at the same time. Coleman’s solo is in two sections — the first, at a very fast tempo, in “typical” Coleman style, that is, with the inventiveness you would expect and a lot of harmonic variety. At the midpoint of the track, Coleman puts out some loud braying notes that seem to signal a break to the bassist and drummer. There is an abrupt pause and the music takes a turn towards medium-up swing. The band romps through the next three and a half minutes, with Coleman evoking more of his R&B history than I have ever heard him do elsewhere. Moffett gets about a minute to solo, with Izenzon feeding him strong root notes. Then Coleman is back with his final statement, just as powerful as before, leading seamlessly into the closing head. “Doughnut” is a breathtaking masterpiece.

Henry Grimes (b): The Call, w. Perry Robinson (cl), Tom Price (dm) (ESP-Disk’, 1966; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Son of Alfalfa” (Grimes). Speaking of fried food, the donut-shaped career of Henry Grimes began with this wonderful session. Between the late ’60s, when he worked extensively with Cecil Taylor, and 2003, Grimes languished in obscurity and near-destitution before his glorious rediscovery in the 21st century and more than ten years of performances in his sixties and seventies, when he tried to make up for all that lost time. The Call was a distinctive first statement, unlike anything his peers were coming up with, and especially notable for four short tunes that proved the avant-garde didn’t have to be garrulous. The reed instrument here is clarinet, not saxophone, but its player is Perry Robinson, to whom attention must be paid. His ancestors on the instrument are not the glassy-toned perfectionists like Benny Goodman and Jimmy Hamilton; he harks back to the woody, earthy qualities of Russell Procope and the eccentricities of Pee Wee Russell.

Henry Grimes (b): The Call, w. Perry Robinson (cl), Tom Price (dm) (ESP-Disk’, 1966; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Son of Alfalfa” (Grimes). Speaking of fried food, the donut-shaped career of Henry Grimes began with this wonderful session. Between the late ’60s, when he worked extensively with Cecil Taylor, and 2003, Grimes languished in obscurity and near-destitution before his glorious rediscovery in the 21st century and more than ten years of performances in his sixties and seventies, when he tried to make up for all that lost time. The Call was a distinctive first statement, unlike anything his peers were coming up with, and especially notable for four short tunes that proved the avant-garde didn’t have to be garrulous. The reed instrument here is clarinet, not saxophone, but its player is Perry Robinson, to whom attention must be paid. His ancestors on the instrument are not the glassy-toned perfectionists like Benny Goodman and Jimmy Hamilton; he harks back to the woody, earthy qualities of Russell Procope and the eccentricities of Pee Wee Russell.

“Son of Alfalfa” accomplishes a lot in three and a half minutes. Is the title a reference to the hayseed character named Alfalfa in the Our Gang comedies? If so, it’s appropriate. The theme is a jagged, goofy line, with a drum break and a squawky burst of noise as a coda, made sharper by Robinson’s acid tone. In this realization, the trio plays the theme twice — the second time without the coda — and jumps into Grimes’s solo immediately, with the bassist quoting motifs of the theme and then engaging in an animated musical conversation with drummer Price. When Robinson joins the discussion, he contributes more fragments of the theme, along with bleats, honks, and the kinds of sounds clarinetists make when they miss their notes. If this sounds like criticism, it’s not. Robinson is an original, smart, downright funny — and still underappreciated, though he had an extensive recording career. There is a quiet moment, which may have been a point in which Robinson expected Grimes to ease back into the theme, but Price keeps going and Robinson comes back in with a second solo in the same spirit. After a tiny rest, the head returns and the tune ends with that squawky coda. (See Grimes’s revisit to this tune some 50 years later, below.)

Sonny Rollins (ts): “Blessing in Disguise” (Rollins) w. Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones from East Broadway Run Down, (Impulse, 1966; hearable via Spotify). Can music be down-home and abstract at the same time? “Blessing in Disguise” may be one of the few examples of this oxymoron in action. This is the only extended trio performance from East Broadway Run Down, since the title track has Freddie Hubbard along for the ride and “We Kiss in a Shadow” is a relatively brief (though elegant) ballad-with-a-beat. “Blessing” immediately recalls the abstract blues of Coltrane’s “Blues to You” (see above), but in this case, the traditional blues release has been stripped away a la John Lee Hooker, leaving an open-harmony foundation on two alternating root notes that is both back-porch simple and blue-sky free.

Rollins chooses not to venture into the stratosphere as some free-jazz players might do here, and he has only three relatively brief improv statements. At first listen, the performance is so loose that it seems formless . . . but that’s not Rollins’s way. In fact, there is a tight structure, loosely interpreted. The theme, such as it is, consists of a rubato section and then a longer section in tempo, with alternations of a five-note phrase over four bars and a silent four bars with a different tonal center, heard only in the bass. The realization of this idea unfolds here in three parts. The first part has the theme, a short Rollins improv, a repetition of the theme, and a Jones solo. The second part has the theme again, a short Rollins improv, another repetition of the theme, and a Garrison solo. The final part has the theme again, a longer and more intense Rollins improv, and the final repetition of the theme. Both bassist and drummer are perfectly in synch throughout. Jones is majestically relaxed, even in his extrovert solo, and Garrison makes the most of his role holding down the tonal centers, with some beautiful triple-stops in his solo that combine the two. Each of Rollins’s first two statements move from loose swing behind the beat to phrases that are outside the beat altogether, with his trademark humor emerging when he plays a paraphrase of the bugle call that precedes horse races as a lead-in to Garrison’s solo. His third statement is climactic, as it should be. Apparently, the only thing left up in the air was the ending, and so Garrison walks on into a fade after Rollins is done

Elvin Jones (dm): Puttin’ It Together, w. Joe Farrell (ts), Jimmy Garrison (b) (Blue Note, 1968; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Gingerbread Boy” (Jimmy Heath). Elvin Jones’s first date as a leader (aside from a session he co-led with Richard Davis in the previous year) was the first principal exposure for saxophonist Joe Farrell, whose thirty-year career shows as much versatility as a career can show – and who, in my opinion, remains underappreciated nonetheless. He is in superb form on this date, as he was when I had the privilege of seeing this trio in action at Slugs in New York City in 1969. “Gingerbread Boy” is perfect. Garrison has never been better recorded; his double-stops underneath the heads are all the harmonic underpinning the tune needs, and when he gets a chance to solo, he uses the technique to suggest “Jeepers Creepers.” Farrell is on fire in his solo, showing the influence of both Coltrane and Coleman. Jones is gigantic, with big jungle-drums tom-tom stuff at beginning and end, and a coiled-spring power through the rest of the track. There is even a sweet twist in the arrangement: after Garrison’s solo, there are some irregular breaks: four bars from Farrell, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Farrell, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Garrison, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Garrison, and finally a long Jones solo that slips back into the jungle drums for the closing head that ritards dramatically for a great conclusion.

Elvin Jones (dm): Puttin’ It Together, w. Joe Farrell (ts), Jimmy Garrison (b) (Blue Note, 1968; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Gingerbread Boy” (Jimmy Heath). Elvin Jones’s first date as a leader (aside from a session he co-led with Richard Davis in the previous year) was the first principal exposure for saxophonist Joe Farrell, whose thirty-year career shows as much versatility as a career can show – and who, in my opinion, remains underappreciated nonetheless. He is in superb form on this date, as he was when I had the privilege of seeing this trio in action at Slugs in New York City in 1969. “Gingerbread Boy” is perfect. Garrison has never been better recorded; his double-stops underneath the heads are all the harmonic underpinning the tune needs, and when he gets a chance to solo, he uses the technique to suggest “Jeepers Creepers.” Farrell is on fire in his solo, showing the influence of both Coltrane and Coleman. Jones is gigantic, with big jungle-drums tom-tom stuff at beginning and end, and a coiled-spring power through the rest of the track. There is even a sweet twist in the arrangement: after Garrison’s solo, there are some irregular breaks: four bars from Farrell, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Farrell, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Garrison, eight bars from Jones, four bars from Garrison, and finally a long Jones solo that slips back into the jungle drums for the closing head that ritards dramatically for a great conclusion.

Open Sky (Dave Liebman [ts], Frank Tusa, Bob Moses): Spirit in the Sky (PM, 1975; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Amy” (Moses). Not all of this date is sax-bass-drums, but the first track shows how beautifully the trio executes that idea, with the caveat that this group is really about the partnership between Moses (not yet Rakalam Bob Moses) and Liebman. I saw them play in the 1970s at the late Club Zircon in Cambridge (Steve Swallow was playing bass, I think), and I can testify to that special rapport between the co-leaders at that time; some 35 years later, Liebman and Moses joined The Fringe for an amazing quintet performance at The Lily Pad, which I wrote about in depth for the Fuse, and their rapport was still astonishing. “Amy” is Moses’s tune, and the trio gives him pride of place in the performance. Liebman begins on tenor without accompaniment, lyrically setting the stage. Not all saxophonists can carry off solo performance, or even cadenzas within group performance, but Liebman’s excellent sense of harmony, informed by a searching quality akin to Coltrane’s spirituality, gives this introduction real weight. Tusa comes in next, with Moses playing brushes, to establish the foundation. Liebman then states the theme, a simple folk-like melody with a brief harmonic twist. In a few seconds, Liebman starts swirling away from the melody and Tusa marks the start of the free-improv section with double-stops. Moses begins “color percussion” almost immediately, counteracting the ballad feel of the melody, and then pushing the group to a more energetic exploration; his percussion grows more interactive and varied as the tune develops, eventually becoming a duet with Liebman and finally a drum improv with support from the saxophone. Liebman plays free throughout but stays close to the root notes of the theme, except for a few passages where he drifts toward the harmonic variation Moses included in the theme. At just the point of maximum group energy, Liebman and Moses together bring the performance down to the original lyricism, and the track fades. This is from a live performance, and presumably the band moved on to another tune without a break.

Sam Rivers (ts): The Quest, w. Dave Holland, Barry Altschul (Pausa, 1976; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Hope” (Rivers). Rivers pioneered the all-out free trio with 1973’s Streams and the tour supporting it, which was deeply influential for years to come. Here, in only seven minutes, is a textbook example of his intuitive music, more economical than Streams and an excellent introduction to his later trio, featuring two more giants, Holland and Altschul. Though there is no head and probably no prearrangement in “Hope,” the structure is cogent and the collective improv is remarkable. At first, there is no tempo and Rivers concentrates on long tones. He then shifts gears, suggesting a blistering 4/4, and Holland falls right in. Some amazing saxophone arpeggios follow, holding to the fast tempo. Then Sam goes all-out, with Holland holding the tempo (sort of), and Altschul providing color percussion. Rivers finally pulls the tempo down for the finish and Holland has a solo arco coda.

Sam Rivers (ts): The Quest, w. Dave Holland, Barry Altschul (Pausa, 1976; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Hope” (Rivers). Rivers pioneered the all-out free trio with 1973’s Streams and the tour supporting it, which was deeply influential for years to come. Here, in only seven minutes, is a textbook example of his intuitive music, more economical than Streams and an excellent introduction to his later trio, featuring two more giants, Holland and Altschul. Though there is no head and probably no prearrangement in “Hope,” the structure is cogent and the collective improv is remarkable. At first, there is no tempo and Rivers concentrates on long tones. He then shifts gears, suggesting a blistering 4/4, and Holland falls right in. Some amazing saxophone arpeggios follow, holding to the fast tempo. Then Sam goes all-out, with Holland holding the tempo (sort of), and Altschul providing color percussion. Rivers finally pulls the tempo down for the finish and Holland has a solo arco coda.

David Murray (ts, vo): 3D Family, w. Johnny Mbizo Dyani, Andrew Cyrille (Hat Hut, 1978; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “3D Family” (Murray). This release memorialized the mighty Murray in a live performance at the Willisau Jazz Festival in Switzerland. If “free groove” is not an oxymoron, “3D Family” is a prime example. The theme is a nine-note ostinato, repeated as obsessively as a theme ever was in a Steve Lacy tune, over a brisk 6/8 pulse, with a contrasting bridge. Even though Dyani and Cyrille are never restricted by this groove, they never leave it behind for more than a few seconds and drive forward with fervor. This motion is maintained for 19 minutes, with the first half taken up by a frenetic Murray solo that offers very little space for him (or you) to breathe. Is it a little too long? At least for me, it seems that Murray has exhausted the possibilities and begins to repeat himself after a while – but his huge artistry is amply manifest here. If Murray’s length dulls your attention, Cyrille’s drum solo will grab your ears smartly and put you back in the groove. HIs approach is melodic rather than percussive, and he introduces unexpected spaces that are a delight. When Murray returns, it is simply to reemphasize the original note-pattern of the theme as a way of transitioning to Dyani’s forceful solo, which has plenty of the strumming that is something of the bassist’s trademark. After Murray has stopped actually playing the nine-note pattern, he continues to sing it under Dyani, and you can hear him quietly giving the bass player a foundation. Each of these players’ personalities is distinctive; the performance may not be an example of genuine give-and-take, but it shows the cumulative impact of three strongly individual soloists offering great ideas in succession.

Air (Henry Threadgill [ss], Fred Hopkins, Steve McCall): Air Lore (Arista / Nexus, 1979; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Weeping Willow Rag” (Scott Joplin). Since so much of Air’s work depends on Henry Threadgill’s composing, Air Lore represented a fascinating side door into their music — two interpretations of classic ragtime by Scott Joplin, two interpretations of Jelly Roll Morton compositions, and one Threadgill original, a ballad respite from the early-jazz feel. “Weeping Willow Rag” opens with a great, musical McCall drum solo. Threadgill then plays the first strain of Joplin’s rag on soprano, deliberately in a behind-the-beat clipped rhythm, against the traditional ragtime feel which is being approximated by Hopkins and McCall, almost as if he is marching to a different drummer. His distinctive tone is well suited to this rhythm — not sensuous, but sinewy and biting instead. As his solo opens up, Hopkins lays down straight swing. Threadgill uses chunks of the melody and stays close to the chords, but occasionally veers away. The second strain of the tune is introduced six minutes later, in a kind of meditative feel, as an intro to Hopkins’s solo, which is full of melody at first and grows more virtuosic as it goes along. Hopkins returns to the meditative feel to lead into Threadgill’s second solo, which begins in the same spirit as his first. The tempo doubles briefly just before the conclusion.

Air (Henry Threadgill [ss], Fred Hopkins, Steve McCall): Air Lore (Arista / Nexus, 1979; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Weeping Willow Rag” (Scott Joplin). Since so much of Air’s work depends on Henry Threadgill’s composing, Air Lore represented a fascinating side door into their music — two interpretations of classic ragtime by Scott Joplin, two interpretations of Jelly Roll Morton compositions, and one Threadgill original, a ballad respite from the early-jazz feel. “Weeping Willow Rag” opens with a great, musical McCall drum solo. Threadgill then plays the first strain of Joplin’s rag on soprano, deliberately in a behind-the-beat clipped rhythm, against the traditional ragtime feel which is being approximated by Hopkins and McCall, almost as if he is marching to a different drummer. His distinctive tone is well suited to this rhythm — not sensuous, but sinewy and biting instead. As his solo opens up, Hopkins lays down straight swing. Threadgill uses chunks of the melody and stays close to the chords, but occasionally veers away. The second strain of the tune is introduced six minutes later, in a kind of meditative feel, as an intro to Hopkins’s solo, which is full of melody at first and grows more virtuosic as it goes along. Hopkins returns to the meditative feel to lead into Threadgill’s second solo, which begins in the same spirit as his first. The tempo doubles briefly just before the conclusion.

Joe Henderson (ts): State of the Tenor, w. Ron Carter, Al Foster (Blue Note, 1985; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “All the Things You Are” (Jerome Kern / Oscar Hammerstein II). Before beginning this survey, I had no idea how savvy this landmark Joe Henderson session was. It is a summation of Henderson’s ability, to be sure, recorded when he was 48, at the height of his powers. And it is one of the best recordings of Ron Carter, free of the trebly quality that too many producers have chosen for him, here capturing his sound (I think) with a mic near his bass rather than with a direct feed from his pickups. The repertoire (and even the setting) show how much Henderson was looking back to the history of the saxophone trio and into the history of jazz itself.

Here is one of Henderson’s own classics, “Isotope.” Here are infrequently-covered compositions by three of the great jazz composers — Ellington, Monk, and Mingus, plus “Soulville” by Horace Silver, no slouch himself as a tunesmith. Here are echoes of Sonny Rollins, in the choice of venue (looking back to Rollins’s groundbreaking 1957 trio recordings at the same NYC club) and the choice of drummer (Al Foster, one of Rollins’s favorites). And there are more nods to fellow saxophonists — Sam Rivers’s “Beatrice,” a beautiful tune dedicated to Rivers’s wife Bea; “The Bead Game,” a free-ish piece Henderson co-wrote with Lee Konitz; and two genuflections to the Godfather, Charlie Parker — Bird’s tune “Cheryl,” and Parker’s so-often-imitated 1945 take on “All the Things You Are.” Henderson’s idea for an arrangement of the standard shows that there’s life in the old song yet. In the 1945 version, Parker wrote a short introductory phrase as an intro to the tune itself, and that phrase has become a necessary addition for dozens of subsequent performers. (The phrase has been described by critic Ted Gioia as “a parody of [Sergei] Rachmaninoff’s Prelude [Op. 3, No. 2] in C-Sharp Minor.” If you listen to Rachmaninoff before Parker, you can hear the similarity of Parker’s intro to the dark, brooding quality of the famous Rachmaninoff theme, and rediscover how well it sets off the major/minor contrasts of Jerome Kern’s melody.) Henderson recognized that this intro provided the kind of modal foundation that Coltrane used so often, and he gives it much more prominence than it has in other recordings, soloing on the idea (without directly quoting it) for almost two minutes as an introduction, and doing it again for another two minutes as a coda. When the Kern theme finally emerges, Foster takes his shuffle beat to a bossa place, and Carter decorates the bass foundation with some perfect harmonics. Henderson’s first solo is a masterful example of what is sometimes called “telling a story” — it unfolds logically and with increasing complexity, finally coming to rest at a place that gives the listener a sense of finality. Carter’s solo starts with a witty idea — a walk in half-time, which few bassists could carry off, but the idea works perfectly here, so when Carter kicks the tempo back into the established time of the tune, the performance gets a little energy boost, and Foster picks up the feel with more active drum support that suggests the exuberance of a Brazilian samba school. Henderson is back with another beautifully-constructed second solo, before leading into the theme and seamlessly segueing to the modal coda. Everything resolves softly two minutes later, and the sparse applause suggests how lucky those fans were to stick around for what was probably the closing tune of a second set. It is hard to imagine how a jazz performance could be better than this one.

Steve Lacy (ss): The Window, w. Jean-Jacques Avenel, Oliver Johnson (RCA / Novus, 1988; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Flakes” (Lacy). Steve Lacy, master of the soprano saxophone and the obsessive theme, made almost 150 recordings as a leader and owned an apartment in the City of Art that he decorated to perfection. His quintets usually had chordal support from pianists, but he made plentiful recordings without chordal instruments, most of which were live dates without the engineering care a discerning listener would like. Among the ones with really superb recording quality are four studio albums he made for RCA / Novus between 1987 and 1992, including this trio date. Avenel and Johnson were long-time members of Lacy’s quintet, and their rapport with him is obvious in every moment of this set. Lacy’s creativity as a composer is just as important as his inventiveness as a soloist, so it is hard to choose among the six tunes in this recording. “Flakes” is perhaps the simplest to describe and the most puckish of the set — it consists of four solo repetitions of a five-note phrase, followed by 24 five-note phrases in the same rhythm, with Avenel providing harmonic shifts underneath using double- and triple-stops, except for the last three, which Avenel plays in unison with Lacy. This description cannot convey the theme’s immediate wit and warmth; it almost demands a smile by the time you reach the last phrase. The individual kernels are so close together that Lacy has trouble making the notes exactly a few times, since he never employed circular breathing, but that is part of the charm of the piece — a constant challenge to the listener’s expectations and the player’s ability. The first to take a solo spot is Avenel, who plays on the rhythmic pattern and displays a kaleidoscope of double- and triple-stopping effects that is astonishing and exquisite at the same time. Lacy is next, playing above the time of his accompanists, who continue to hold on (loosely) to the stop-time qualities of the theme. As ever, his solo is a witty collection of melodic bits and sound effects, and Avenel’s beautiful playing, with more double- and triple-stops, almost steals the show. Johnson, a drummer who owes a lot to Elvin Jones, has a more prominent role elsewhere in the set (he has a great solo on “Window”) but is subtly vital here, playing lightly with brushes and filling the spaces elegantly. This is a prime example of Lacy’s many potato-chip performances: when it’s over, you just want to hear another one.

Branford Marsalis (ts): Trio Jeepy, w. Milt Hinton, Jeff “Tain” Watts (Columbia, 1989; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Peace” (Ornette Coleman). What a great idea Branford Marsalis had here – to join forces with Milt Hinton, 79 at the time of this recording, a monumental bassist who could play anything from traditional two-beat to the most complex lines George Russell could write. With Hinton on board, nothing could be out of bounds in the repertoire, so the tunes range from the ancient standard “Makin’ Whoopee” to Billy Strayhorn’s “UMMG” to Sonny Rollins’s “Doxy” to this Ornette classic. Their version of “Peace” is a complete gem, one of the very best things Marsalis has ever done. Hinton’s characteristic walking style, just microseconds behind the beat, is a key to success here – a firm foundation is never in doubt, but the ease of it gives the saxophonist a supremely relaxed environment in which to work. Marsalis adds a little wrinkle to Coleman’s initial arrangement – a short bass interlude between the two statements of the theme, giving Hinton a chance to show off his understanding of Coleman’s harmonic freedom. Marsalis solos with a superb balance between classic swing and modern invention. He slips from one harmonic center to another with ease; he plays with the beat and above it; he quotes the motifs of the theme and motifs from other Coleman tunes. And Hinton is uncannily with him for every step, shifting harmonies, holding the bottom when Marsalis slips away from it, and occasionally tossing in tiny rests that echo the break Coleman put in the original tune. Watts is an appreciative supporter of this extraordinary partnership, always offering tasteful comments and never trying to dominate the conversation.

Branford Marsalis (ts): Trio Jeepy, w. Milt Hinton, Jeff “Tain” Watts (Columbia, 1989; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Peace” (Ornette Coleman). What a great idea Branford Marsalis had here – to join forces with Milt Hinton, 79 at the time of this recording, a monumental bassist who could play anything from traditional two-beat to the most complex lines George Russell could write. With Hinton on board, nothing could be out of bounds in the repertoire, so the tunes range from the ancient standard “Makin’ Whoopee” to Billy Strayhorn’s “UMMG” to Sonny Rollins’s “Doxy” to this Ornette classic. Their version of “Peace” is a complete gem, one of the very best things Marsalis has ever done. Hinton’s characteristic walking style, just microseconds behind the beat, is a key to success here – a firm foundation is never in doubt, but the ease of it gives the saxophonist a supremely relaxed environment in which to work. Marsalis adds a little wrinkle to Coleman’s initial arrangement – a short bass interlude between the two statements of the theme, giving Hinton a chance to show off his understanding of Coleman’s harmonic freedom. Marsalis solos with a superb balance between classic swing and modern invention. He slips from one harmonic center to another with ease; he plays with the beat and above it; he quotes the motifs of the theme and motifs from other Coleman tunes. And Hinton is uncannily with him for every step, shifting harmonies, holding the bottom when Marsalis slips away from it, and occasionally tossing in tiny rests that echo the break Coleman put in the original tune. Watts is an appreciative supporter of this extraordinary partnership, always offering tasteful comments and never trying to dominate the conversation.

Joe Lovano (ts): Sounds of Joy, w. Anthony Cox, Ed Blackwell (Enja, 1991; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “23rd Street Theme” (Lovano). At its essence, this session is a love letter from Lovano to Blackwell, a deep bow from a contemporary master to a master of a previous generation. Blackwell, who battled kidney disease for decades, died just twenty months after the session, but he plays here with undiminished verve. He was among the most “African” of jazz drummers, bringing a personal stamp of pitch and dynamics to every session in which he worked, from the brilliant Eric Dolphy live recordings at the Five Spot, through many great Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry small group sessions, to the cooperative group Old and New Dreams, to a plethora of pickup dates with musicians ranging from Art Neville to Anthony Braxton. Sounds of Joy stands as one of his most significant recordings because Lovano gives him a status in most of the tunes that is almost like co-leadership. Throughout, you listen primarily to the remarkable interplay between Blackwell and Lovano, with the drummer responding to hints from the saxophone and subtly changing the acoustic space in which Lovano works with small shifts in his percussion choices. If Cox has a subordinate role here, he still fills it with great taste. “23rd Street Theme” is a bright, lively tune, a carefully-disguised contrafact of a popular song which fools my ear but peeks out tantalizingly in the Cox and Lovano solos. The performance begins with a short drum break that recalls Blackwell’s New Orleans roots – a sort of martial flourish, as if he is calling a group of parade marchers to order, followed by a polyrhythmic juxtaposition of cowbell and snare. Lovano and Blackwell play the melody of the theme together, with Cox providing a low countermelody, and then Cox offers a fleet and well-constructed solo, with Blackwell gently pushing him with brushes on snare. Blackwell marks the very end of the bass solo with a couple of well-positioned cymbal taps, and Lovano comes in for his say. The drummer immediately shifts to ride cymbal and snare accents, but no element of his accompaniment stays in place for very long, and he changes colors frequently as Lovano rips fluidly thorough his choruses. Finally, Blackwell gets a solo spot which is almost a conversation between his snare drum and the rest of his kit. It comes to a close with some bold flashes on one of his special cymbals, and the theme returns.

Kenny Garrett (as): Triology, w. Kiyoshi Kitagawa, Brian Blades (Warner Bros., 1995; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “In Your Own Sweet Way” (Dave Brubeck). Garrett is plenty versatile, and this session is welcome because it allows us to hear him in a simple setting, with a nice mix of standards, tunes by other players, and originals. It also is one of the few trio recordings featuring the alto sax. Garrett chooses to interpret “In Your Own Sweet Way” wisely – not sweetly or schmalzily, but with some humor, a squeeze of lemon, and a little bounce, provided with a light touch by Brian Blades. After the theme, he gets a short interlude with pedal tones that sets up his snappy solo, firmly on the changes. Another pedal-tone interlude introduces Kitagawa, who handles himself well and shows off good technique. Pedal tones come in again and Garrett restates the melody, this time a bit more freely than at first. His close brings the energy down for a final statement over the pedal tones and the tune lands softly.

The Fringe (George Garzone [ts], John Lockwood, Bob Gullotti): Live in Israel (Soul Note, 1995; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Our Fathers” / “On the Hump” / “Desert Time” (credited to The Fringe collectively). It’s time to check in with The Fringe, twenty-five years after they began their remarkable tenure as the world’s longest-lived free jazz band. This recording, from a concert at the Red Sea Jazz Festival, comes ten years after John Lockwood had replaced Richard Appleman on bass. The format of their Red Sea set was typical for a Fringe set in a “small-scale” context at the time – a couple of short tunes framing two long free-form interactions, with tiny breaks between the parts. In their many 21st-century performances at The Lily Pad in Cambridge, even this semblance of structure could be abandoned, and a set might consist of one long multi-part improvisation without any prearrangement. Here, the first of the long interactions (about 22 minutes of continuous music) seems to have one prearranged set of chord changes (identified as “On the Hump,” in a pseudo-tango rhythm) and a fast swing section (identified as “Desert Time”). “On the Hump” is introduced by a long bass solo and a contemplative sax improvisation (“Our Fathers”). “Desert Time” is introduced by a long drum solo. There isn’t space here to detail every moment of the performance, but each member of the group contributes masterfully to it. Lockwood’s solo on “Our Fathers” is mostly pizzicato, showing off his lovely singing tone, strumming, and double- and triple-stops. Once he establishes the tango rhythm, he is firm without being restrictive, and in the fast-swing, he provides the force of a freight train. Gullotti’s percussion support shows his deep rapport with the other two players, but he remains delicate and light throughout, taking his solo entirely with brushes, using the tonal values of his tom-toms, and then maintaining brushes even in the fast-swing section (his stickwork comes forward in the following part of the performance.) Garzone is simply monumental in his three tenor statements, using the entire range of his horn and even varying the sonic quality from time to time – there are huge honks of sound and thin reedy filigrees that contrast with his “normal” robust approach. HIs first statement is mostly lyrical, built logically on a single root note. The second, in the tango section, adheres loosely to the chords suggested by Lockwood, still using the same root. The final one is built on a different tonal center, and it is as varied and powerful as anything I have ever heard from this master saxophonist – it could be studied by anyone who wants to know how a soloist can provide extended sonic variety on a modal foundation. It has a beautiful shape, rising to a climax, and then subsiding, with a thin trickle of notes as he steps away from the mic. To experience The Fringe as it is today, and as you should see them – live, in three dimensions – we will have to wait for the lifting of the Coronavirus restrictions and their reinstatement at The Lily Pad on Monday nights, where Garzone and Appleman have performed this year with guest artists, hearing the late Bob Gullotti’s drumming in their heads. It will be worth the wait.

Ornette Coleman (as): Sound Grammar, w. Gregory Cohen (pizzicato b), Tony Falanga (arco b), Denardo Coleman (Sound Grammar, 2006 [recorded 2005]) – Notable track: “Waiting for You” (not hearable via Spotify, but uploaded to YouTube [link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UL0JRCI2dQM]). This is the recording that won Coleman the Pulitzer Prize for composition, although that award was really how the Pulitzers chose to recognize a lifetime of achievement. There is nothing unusual or groundbreaking about the compositions here, which include “Turnaround” and “Song X,” both previously recorded. The real significance of the recording is its documentation of one of Ornette’s most inspired ideas for an ensemble – a two-bass quartet in which one bassist plays almost exclusively arco and the other almost exclusively pizzicato. The foundation provides two streams of sound beneath Coleman’s improvisations, and he is freed to be lyrical or driving as he chooses without changing the gears of the group. “Waiting for You” shows brilliantly how this works. After an introduction by the bassists, in which Falanga is plaintive and stark, Coleman states the melancholy theme and then moves quickly into improvising over the three supporting players. Gradually, Cohen introduces a fast walk, while Falanga holds to the austerity of the beginning. Ornette partakes of both moods in his solo, which gradually picks up energy. He brings things to a climax with a quote from his own “Dancing in Your Head,” and Denardo kicks the ensemble into gear for a final minute of steamroller intensity. Ornette plays the theme over this active foundation, and the piece is over.

JD Allen (ts): Shine!, w. Gregg August, Rudy Royston (Sunnyside, 2009; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Ephraim” (Allen). JD Allen is a 21st century saxophonist — that is, he sees no point in limiting himself to playing in tempo or using open forms. In order to be a complete musician, he wants to be adept in both styles and in everything in between. (To hear him in tempo, see Barracoon in the “more to explore” section below.) “Ephraim” shows him in a free-ish context. The theme consists of a lyrical section, with long singing tones underpinned by arco bass, a contrasting lyrical section, like a bridge, and a fast section built on repetition of a four-note staccato phrase, which begins with a sort of Spanish modality. Allen’s solo is in two parts, using the staccato phrase and the long tones as motifs in a long line of musical thought, supported freely by the bass and drums, with the exception of Royston’s high-hat cymbal, which keeps a constant pulse in fast time. The two parts of the saxophone solo are clearly delineated by Allen’s statements of the harmonies of the “bridge.” After the second part, August and Royston duet briefly, with August emphasizing his low notes and playing very percussively. Allen then comes back in to restate the lyrical section and bring things to a satisfying close.

Marcus Strickland (ts): Idiosyncrasies, w. Ben Williams, EJ Strickland (Strick Muzik, 2009; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Middleman” (Marcus Strickland). Strickland is a brilliant technician with a pan-tonal approach to composing, and this trio date strips his art to its essence. No one track can really do him full justice, but “Middleman” is a driving swinger, with a clever shift to triple-time in its theme. After the first theme statement, Williams gets a full-bodied solo with wonderful shimmering percussive support from Marcus’s brother EJ Strickland. Marcus takes the central position, and his solo rips, rigs, and careens along, maintaining the time-shift for a nice tempo variation. Then EJ has his solo — another demonstration of his ability to color the space — and the closing head wraps things up.

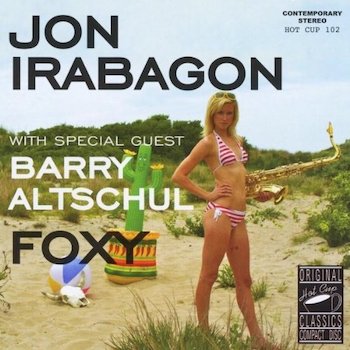

Jon Irabagon (ts): Foxy, w. Peter Brendler, Barry Altschul (Hot Cup, 2010; hearable via Spotify). I have been mightily impressed with Irabagon since hearing him with Mostly Other People Do the Killing, and this outing is a comprehensive (perhaps even exhaustive) demonstration of just how good he is. The cover of the CD is a deliberate homage to / parody of the cover of Sonny Rollins’s Way Out West, and its title is another Rollins reference, to his tune “Doxy.”

Jon Irabagon (ts): Foxy, w. Peter Brendler, Barry Altschul (Hot Cup, 2010; hearable via Spotify). I have been mightily impressed with Irabagon since hearing him with Mostly Other People Do the Killing, and this outing is a comprehensive (perhaps even exhaustive) demonstration of just how good he is. The cover of the CD is a deliberate homage to / parody of the cover of Sonny Rollins’s Way Out West, and its title is another Rollins reference, to his tune “Doxy.”

The Rollins tune does not appear; in fact, despite the listed CD breaks, there is no interruption in more than 75 minutes of music. The first track fades up, and the last track abruptly cuts off without even a fade. In between the two, Irabagon maintains a killing pace, never less than medium-fast, without a single break for a bass or drum solo. This is no less taxing for Brendler and Altschul, who must (and do) deliver rock-solid and mostly in-tempo support. It is collective improvisation, but the idea is to swing as much as possible with as much freedom as such swinging will allow. There are moments when it sounds like Irabagon is soloing on familiar changes. (in fact, Troy Collins, in his All About Jazz review of the CD, maintains that the entire thing is based on 16-bar forms.) The marathon almost becomes a kind of test to the listener to see how many tunes he or she can identify as they rocket by. I heard Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time,” played in the form of “The Hucklebuck.” Collins heard “Let It Snow.” We both heard “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered.” Foxy is unlike any other saxophone trio date recorded so far, and it is very likely to stand as the only one of its kind ever.

Steve Adams (as): Surface Tension, w. Ken Filiano, Scott Amendola (Clean Feed, 2011 hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Squelch” (Adams). Adams had a long history in eastern Massachusetts before moving to the Bay Area. He’s now a member of the venerable ROVA Saxophone Quartet as well as a leader in his own right. In our area, he played with Birdsongs of the Mesozoic and showed his composing chops as one of the Composers in Red Sneakers. A propos of this survey, I remember him well as a counterpart of Allan Chase in Your Neighborhood Saxophone Quartet, an extrovert freewheeler in contrast to Chase’s cool intellectual. “Squelch” offers another point of comparison with Chase — though Adams was known in Boston primarily as a tenor player, this CD shows off his chops on sopranino, baritone, bass flute, and here on alto, which was Chase’s primary axe in YNSQ. The tune is a jokey, swinging line in two parts, that leads into a fluid Adams solo that’s very much in the same spirit, smart and witty at the same time. It’s an additional treat to hear another ex-Bostonian, Ken Filiano, playing bass superbly here, and soloing with great dexterity, singing along with his lines as he used to do memorably in our town. Amendola doesn’t have a solo as such, but his support is splashy and energetic.

Fly (Mark Turner [ts], Larry Grenadier, Jeff Ballard): Year of the Snake (ECM, 2012; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Salt and Pepper” (Turner / Ballard). Fly is a cooperative trio, and most of their music is pantonal and abstract, allowing plenty of room for interaction. “Salt and Pepper” is atypical for them, but it serves as a good introduction and a demonstration that they can be effective in more traditional forms. The tune itself is an easy medium-slow groove, almost a classic 32-bar form (with the exception of the bridge, which is only four bars long). Turner plays it softly at first, with some high-note shouts and more polytonality as he goes along in his short solo. Grenadier solos next, staying close to the original feel and showing admirable ability. Only at the end do they leave straight time and venture into free territory, which is done so smoothly that the group improv works beautifully as a coda.

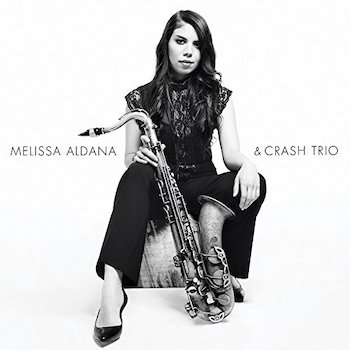

Melissa Aldana (ts): Melissa Aldana & Crash Trio, w. Pablo Menares, Francisco Mela (Concord Jazz, 2014; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Bring Him Home” (Aldana). This was Aldana’s first date as a leader, with Chilean bassist Menares and Cuban drummer Mela. She shows almost equal respect for Coleman and Henderson, and demonstrates excellent rapport with her supporting players. “Bring Him Home” has an agreeable swinging theme that starts in one tonality and slips around before concluding with an out-of-tempo coda. Aldana’s solo begins economically, but she soon shows that she has chops and smarts, bouncing into tempo and out again with aplomb. Menares and Mela listen closely to her and respond to her twists and turns. To wrap up, she inverts the order of the first head, playing the out-of-tempo coda and then going back into the main theme.

Melissa Aldana (ts): Melissa Aldana & Crash Trio, w. Pablo Menares, Francisco Mela (Concord Jazz, 2014; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Bring Him Home” (Aldana). This was Aldana’s first date as a leader, with Chilean bassist Menares and Cuban drummer Mela. She shows almost equal respect for Coleman and Henderson, and demonstrates excellent rapport with her supporting players. “Bring Him Home” has an agreeable swinging theme that starts in one tonality and slips around before concluding with an out-of-tempo coda. Aldana’s solo begins economically, but she soon shows that she has chops and smarts, bouncing into tempo and out again with aplomb. Menares and Mela listen closely to her and respond to her twists and turns. To wrap up, she inverts the order of the first head, playing the out-of-tempo coda and then going back into the main theme.

Jason Stein’s Locksmith Isidore (Jason Stein [bcl), Jason Roebke, Mike Pride): Three Kinds of Happiness (2010; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Ground Floor South” (Stein). At last, a trio featuring the bass clarinet. Their label explains that the group’s name “comes from [Jason] Stein’s grandfather, a master locksmith who didn’t trust banks and hid his money inside an old sofa in his attic.” The grandson is to be applauded for working consistently in the trio format and for making himself the big clarinet’s eloquent ambassador in the new century, so many years after Eric Dolphy pointed the way.

However, Stein is not following in Dolphy’s wake stylistically. His approach is more linear and less speech-like, more in the line of saxophonists Joe Henderson and Wayne Shorter, though he obviously knows Coleman and Lacy as well. His compositional range is impressive — he writes everything from straight-ahead pieces (even a popular-song contrafact called “26-2” on his most recent CD, After Caroline) — to open improv, and his group is a well-oiled unit that handles anything he throws at them. “Ground Floor South” is two tunes in one — a Lacyish first theme and a second one in a darker mood. The first part, established over a clip-cloppy rhythm, has four repetitions of a seven-note figure, with the second and fourth reps given multi-note tags. This sets up Roebke’s arco solo, conversational rather than virtuosic, with Stein playing the theme more and more softly under him until it is barely audible. Pride comes in quietly for a short transition, and the trio moves into the second theme, meditative and a little melancholy at first, and then dropping into tempo for a noirish walk. The alternation of moods continues as Stein solos over the shifts, showing that he can swing delicately and smear convincingly. Roebke and Pride establish a firmer foundation under the melancholy mood as the solo develops, and things wrap up smartly after the theme recap with a definite full stop.

Henry Grimes (b): Us Free: Fish Stories, w. Bill McHenry (ts), Andrew Cyrille (dm) (Fresh Sound, 2014; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Son of Alfalfa” (Grimes). As a wrap up to this survey, I can’t resist recommending this remake of a tune I selected earlier, and I particularly recommend hearing it side-by-side with the original recording from nearly 50 years before (see above). The arrangement is almost exactly the same as it was in 1976, except for the fact that McHenry has the first solo (on tenor saxophone rather than clarinet) and Grimes makes his statement arco. No one could replicate what Perry Robinson did in the first recording, which is just as well. McHenry’s more conventional sax sound doesn’t lessen the humor in the heads, and he brings more depth to his improvisation because he has more time to work with. Grimes throws shards of the theme into his solo, but he also is more serious about things than he was in his salad days. Rather than the cartoonish brevity of the original, this version runs a bit more than six minutes — still short by avant-garde standards — and it even includes a fine solo from Andrew Cyrille, with whom Grimes worked in Cecil Taylor’s group. It still makes me smile.

More to explore:

The Murray, Bloom, and Fringe recordings below all deserve CD reissues. I include them here to recognize their importance and pull the coattails of eminent producers. Michael Cuscuna, are you out there?

Sonny Rollins (ts): A Night at the Village Vanguard: The RVG Edition, w. Donald Bailey, Wilbur Ware, Pete La Roca, Elvin Jones (Blue Note, 1999 [recorded November 1957]; six tracks were originally issued in LP form as A Night at the Village Vanguard [Blue Note, 1958]; ten additional performances were issued in a 2-LP set called More from the Vanguard [Blue Note, 1975]; this CD compilation reissued all the LP material and two more tracks; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “I Can’t Get Started” (Vernon Duke / Ira Gershwin). Bob Blumenthal recommends this track, and his description can’t be improved upon: “Sonny calls the entire ballad tradition into question by alternating straight and serious melodic lines with bellicose, slapstick quotes; the process is not unrelated to the later and more extreme ballad work of Albert Ayler.” A landmark recording, despite the sound of the drums, showing that even master engineer Rudy Van Gelder could have his off-days. The CD remastering improves the sound a bit.

Elvin Jones (dm) & Richard Davis (b), w. Frank Foster (ts): “Shiny Stockings” (Foster), from Heavy Sounds (Impulse, 1967); hearable via Spotify) – The only trio track from this Jones-Davis session is also the only trio performance I know of featuring an underappreciated saxman, Frank Foster.

John Coltrane (ts) & Rashied Ali (dm): Interstellar Space (Impulse, 1974 [recorded 1967]; “Expanded Edition” CD version issued 1973, with additional tracks; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Saturn” (Coltrane). A completely improvised duo session with drums, the only one of Coltrane’s career.

Sam Rivers (ts/fl/p/ss): Streams, w. Cecil McBee, Norman Connors (Impulse, 1973; hearable via Spotify) – A continuous improvisational performance in which Rivers moves from tenor sax to flute to piano to soprano saxophone.

David Murray (ts): Low Class Conspiracy, w. Fred Hopkins, Phillip Wilson (Adelphi, 1976; not reissued on CD and not hearable via Spotify; the full LP, surface noise and all, has been uploaded to YouTube; see link below) – Notable track: “Dewey’s Circle” (Murray). Murray’s first date as a leader, and still impressive. YouTube link. “Dewey’s Circle” begins at 7:05.

Jane Ira Bloom (ss) & Kent McLagan (b): We Are (Outline, 1978; not reissued on CD and not hearable online) – Notable track: “Cahoon” (Bloom / McLagan). Bloom’s first recording, self-produced, is a duo with a superb bassist that shows she was brilliant from the very beginning.

Air (Henry Threadgill [ts], Fred Hopkins, Steve McCall): Live Air (1980; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Be Ever Out” (Threadgill). A fine example of Air in a surprisingly funky mood.

The Fringe (George Garzone [ts], Richard Appleman, Bob Gullotti): Live! (ApGuGa, 1980; not reissued on CD and not hearable on-line) – Notable track: “For Alicia” (Gullotti). Another memorial to the late great drummer, recorded earlier than the track selected above, with The Fringe’s first bassist — all three playing at the top of their game.

JD Allen: Barracoon w. Ian Kenselaar, Nic Cacioppo (2019; hearable via Spotify) – Notable track: “Communion” (Allen). An in-tempo track by the always-excellent Allen.

I am indebted to the writers cited above and to many others whose recommendations sent me in interesting directions, and especially to Josh Jackson, “Shoot the Piano Player: New Jazz Trios,” NPR Music, September 23, 2009, and to Michael J. West, “JazzTimes 10: Great Saxophone Trio Albums” (revised version), JazzTimes, April 26, 2019

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Air, Albert Ayler, Bob Moses, Bradford Marsalis, Dave Liebman, David Murray, Elvin Jones, Fly, Henry Grimes, Henry Threadgill, JD Allen, Joe Henderson, Joe Lovano, John-Coltrane, Jon Irabagon, Kenny Garrett, Lee Konitz, Marcus Strickland, Mark Turner, Melissa Aldana, Ornette Coleman, Sam Rivers, Saxophone trio, Sonny-Rollins, Steve Adams, Steve Elman, Steve Lacy

Some good choices, a few known classics and a few new ones. Some modern trios I would suggest: Sonny Simmons “Ancient Ritual” 1994;

Tim Berne “Paraphrase” 1995; Julius Hemphill “Live Trio” (sax-cello-drums).

This is an absolutely wonderful article on one of my favorite Jazz groupings. I had a number of these album, but your comments really brought them alive for me. Plus I discovered seven new albums that I added to my collection. I now have 122 Saxophone Trio albums in a playlist that are some of my most cherished jazz.

Thank you, Steve!

Check out the Alex Jenkins Trio. There’re latest record is called Black Bird and got a 4 star review in All About Jazz!