Theater Feature: An Interview with Benny Sato Ambush on Directing the Virtual Reading of Anthony Clarvoe’s “The Living”

“A play like The Living pricks the conscience of the country. It is the reason I wanted to produce and direct it.”

Editor’s Note: The interview below with director Benny Sato Ambush is a companion piece to the superb talk that dramaturge Hanife Schulte had with dramatist Anthony Clarvoe about a Zoom theater reading of his play The Living. The Arts Fuse provided underwriting for this staging last May, a benefit for Boston’s Theater Community Benevolent Fund.

Given the many illuminating things the justifiably proud Ambush has to say about the show, I will be brief. For me, it was a terrific experience. I am proud of having helped to make such a beautifully acted presentation possible (speaking as a self-interested critic, of course) and to contribute to such a worthy cause. What’s more, the show put the magazine’s money where its editor’s mouth is: I believe that theater in the present (and in the post-COVID future) must speak to an increasingly difficult reality, and to use technology to enhance drama’s power and reach. We no longer have the luxury to ignore Herculean conflicts — political, social, and environmental — that threaten our very existence. Theater must not sidestep its historic responsibility to disturb the status quo by probing, reflecting, and clarifying what’s at stake in these clashes. The Living furnishes a bold model.

— Bill Marx

Hanife Schulte: What inspired you to direct Anthony Clarvoe’s The Living in Zoom theater?

Benny Sato Ambush: We were all in COVID-19 lockdown last spring. I was looking for things to do because COVID abruptly shut down all my freelance directing work overnight. The entire arts community was feeling frustrated that our artistic and creative work had been stalled. Several inspirations led me to this project.

One was Ken Cheeseman, my friend and colleague from my Emerson College teaching days, who had sent out a message on Facebook to his friends, including me, about these new digital tools we now have, and he asked his fellow theater artists, “Should we take advantage of them?” I replied, “Count me in.” He replied, “Let’s have a conversation about what we can do with these new tools.”

The other contributing inspiration came from Bill Marx, editor-in-chief of Boston’s Arts Fuse online arts magazine, who began publishing essays about how the plague had been represented on stage and in literature throughout history. I found his writing illuminating. It jogged my memory of a production of Anthony’s The Living that I had seen about 17 years ago when I was teaching at the North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. It is now called the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. I did not remember the specific details of that production, but I distinctly remembered being tremendously impacted by it emotionally. I knew it had something to do with a plague. I contacted Bill and asked him if he knew about The Living. He said he didn’t. Bill ordered the play, but it took a long time for it to get to him because the Postal Service was really slow back then because of all the COVID-19 disruptions. So, I reached out to Anthony directly because I’d known him for a couple of decades. I directed a play of his in Anchorage, Alaska in 1995. Anthony emailed me a copy before the published version got to Bill. We both read it and thought it was amazing and relevant to what is going on now with our COVID-19 pandemic.

In one of the interviews that Anthony did when the play was new back in the early 1990s, he was quoted as saying about his research for the play, “it was as if my ancestors were speaking to me.” For me, producing and directing The Living during the COVID era was a slam dunk necessity. Anthony wrote The Living 29 years ago, in 1991. I told him I thought his soul must have known when he was writing it back then, that we would need it 29 years later in 2020 to say something to us during our current scourge.

Bill gave it a thumbs up and asked, “How can we get it out there?” I thought at first to do a live, one-night-only Zoom virtual reading. I reached out to Ken about it, and he was all in. I cast the show in my head, thinking of actors in the Boston area whom I’ve known, some whom I’ve worked with, others with whom I’ve always wanted to work. I put together a dream cast in my head, wrote up an invitation letter, emailed it to them, and they all said yes! Then, I thought to get people around me that I needed to put it together. I invited you, Hanife, to dramaturge this virtual production because of our work together years ago in my Emerson Stage production of Anything to Declare? I wanted to ground myself and the cast in the historical period, in your scholarly research, to make sure that we understood what we were saying.

I really didn’t understand much about this digital stuff as I’m a digital immigrant. So, I thought we needed somebody on the team who was digitally savvy. But who? I had seen many promo emails from most of the theaters in the Boston region. The ones that impressed me the most were the ones coming out of Central Square Theater. There was something about their promo videos for upcoming shows that were clean and well put together. I liked the look of them. So, I called my friend Debra Wise, the artistic director of the Underground Railway Theater, one of the two resident theater companies at Central Square Theater. I asked her who was their digital person. She said, Nina Groom, whom I met a year earlier when I directed a play for the Underground Railway Theater. I reached out to Nina and invited her to join the effort. She said yes! I had the digitally savvy technical person the project needed. Then, I asked myself, how do I organize all of this? I went to stage manager Becca Freifeld, whom I love and have worked with before. She said yes! I also reached out to my go-to composer and sound designer, the world-class Dewey Dellay. He said yes! Boom, I had my team.

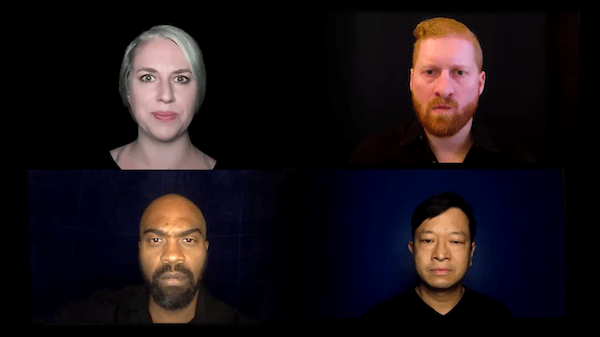

Samantha Richert – upper left; Maurice Parent – lower left; Ed Hoopman – upper right; Michael Tow – lower right, in the the Zoom Theatre production of The Living.

HS: What was your approach towards Zoom theater? How did you imagine working with the team on Zoom?

BSA: All along the way, I was researching examples of live Zoom theater: live public presentations of theatrical works streamed in real time through the Zoom platform on laptops and cellphone screens. I was looking at many of the live Zoom theater invitations that all of us were getting in our inboxes. There were a lot of them, and I didn’t like much of what I was seeing: audio glitches and distortions, seeing everyone’s backdrop (plants, bookcases, living rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, ceilings), screens freezing. I would hear ambient noise in the background like motorcycles, sirens, loud voices, dogs barking, subway trains passing by. I saw a cat walking across a laptop during a live virtual presentation. Family members would pass by or walk in the background saying, “oops, sorry, sorry, sorry.” Poor and inconsistent lighting and audio volume. Those kinds of things weren’t working for me. I was looking for artistic integrity for my first foray into Zoom theater.

I thought if this was going to be a COVID-19 response from the Boston theater community that I put out into the world, we needed to stand proudly behind it. I learned from our digital technical designer/editor that we could use a third-party software to interface with Zoom to edit a live recording in postproduction. That would allow us to do things like fade counts, add graphic images, music, sound effects, and choose where actors appeared on the screen. We could get rid of the hard line around the rectangular boxes that light up every time someone speaks. We could also get rid of the identifying name tags. We could have some artistic and aesthetic leeway. So, I pivoted and decided to go with the prerecorded/edit-in-post route rather than do it virtually live. I sent out another round of emails to get permission from the cast to do it the prerecorded/edited way, and all the participants said yes. That led to some intense scheduling, which is why having Becca as our stage manager was so important because she is an organizing wizard. That’s how we ended up doing the project as an edited prerecorded virtual offering.

HS: In Zoom theater, it sounds like you really cared for the aesthetic aspects of what the virtual audience would see on their screens. How did you implement your theatrical aesthetic while directing the play in a virtual space?

BSA: The recordings of The Living were all done in May 2020 scene by scene over five days. None of us ever met physically. We never even read the play together like we normally would do in live in-person theater. We really didn’t have the time to do that. We had extraordinarily little rehearsal time for this due to everyone’s crazy schedule. All of them were recorded on Zoom. We edited using other software. Once we edited and exported the video file, we presented it on a YouTube channel that we created for the Theater of the Blue Marble, the banner under which it was produced, generously underwritten by Bill Marx and his Arts Fuse online arts magazine. Theater of the Blue Marble is my independent producing entity. The beauty of Zoom theater is that you can work on a piece of theatrical art from the convenience of wherever you are, capture it, and present it to a global public.

Once we started recording a scene, I let the actors go all the way through the scene and did not interrupt them unless there was a major technical glitch like a screen freezing or a major audio distortion. If we had time to do an additional take, I would give the actors notes after the previous take was completed. But in terms of working moment-to-moment like we are accustomed to doing in live in-person theater, we didn’t have the time to do that.

I was happy with the aesthetic we arrived at that was inspired by an image I had in mind: the way jewelers present diamonds on a square or rectangle of plush black velour or velvet. Brilliant light reflects off and through the diamond against the black field of velour, and the diamond visually pops. That was the aesthetic image of my approach.

You can’t really do a lot physically on Zoom because the screen is so small. What was more important for me was to get the words out, to get the story out cleanly. I opted not to use English accents because we wanted the story to be delivered clearly and lucidly. To do accents properly takes a lot of time, and we didn’t have that kind of time or a dialect coach.

We did very tight camera framing on the screen: the head, neck, and down to just below the top of the shoulder line so that the actors would be very present and as large as possible on the screen. We were digitally able to eliminate the hard line around the rectangle. I asked all the actors to find something dark as a backdrop, whatever they had, anything black or dark. One actor didn’t have something black, but he had something dark blue. Nina, our video editor, was able to digitally alter things a bit to create a sameness of dark as much as possible to create that image of a sea of blackness behind diamonds (actors’ faces) visually popping. We lit faces and necks to pop like a diamond with a sea of blackness behind them without the hard line outlining the Zoom rectangle. Then, Nina told me she could move the actors on the screen. When she showed me that, I almost fell out of my chair with glee. Wow, you can approximate a kind of staging! So, that was the aesthetic I chose: these diamonds of actors against a sea of blackness who appeared up close and present, looking right into the camera, moving when appropriate.

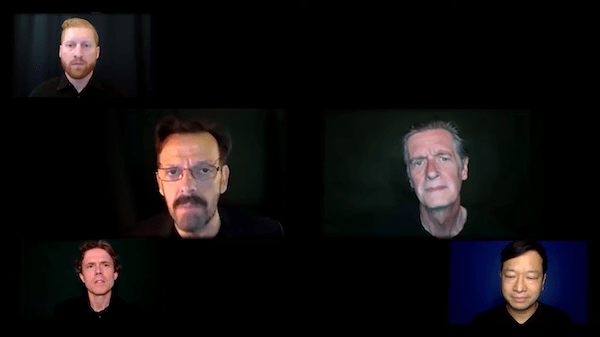

Anne Gottlieb – top center; from left: Samantha Richert, Nael Nacer, and Doug Lockwood, in the Zoom theater production of The Living.

HS: What is missing in Zoom theater? Would you identify anything that doesn’t give you the same feeling you get when you are in the theater, you engage with the public, or you see actors on stage?

BSA: You can see Zoom theater at any time, which is a great convenience, but it is not the same as live in-person theater. It’s a different thing. Zoom theater is more like watching a Netflix movie on your laptop or your cellphone. First, you don’t have a public audience together with you in shared physical space watching. The unique feature of live in-person theater is that you have an audience physically together sitting next to each other, breathing the same air as the performers and backstage personnel. You are in the same shared physical locality. In Zoom theater, you don’t have that real-time immediacy of live in-person theater because you could watch the movie by yourself from anywhere. You don’t have a group audience experience. You could have somebody watching next to you on the same laptop or the same cellphone screen, but you don’t have hundreds of people with you.

When putting The Living together, we were never together in person, in shared physical space. We were in virtual space. The actors were recording from wherever they lived, wherever they were: Provincetown, Massachusetts, Lynn, Massachusetts, Somerville, Boston, western Massachusetts, etc. The uniting feature was the screen, which is inanimate. The screen is not a living thing. It’s a representation of the real thing. You don’t have the same emotional, energetic connection. A live in-person performance is a transfer of energy. You can feel it. What actors do in the craft of acting is read and respond to energy from and to each other, read and respond to energy from and to live audiences. You don’t really have the same kind of energy transfer on screen. And, although a Zoom viewer can be made to feel things, it’s not the same as live in-person theater.

HS: What kind of challenges did you encounter while working with professional actors in virtual space?

BSA: The challenge for this effort was that we had very little time to actually mount the virtual production, so we weren’t able to rehearse other than literally moments before we recorded. I didn’t have a chance to give many notes because we only had time to do maybe two or three takes for each scene. If we had had more time, I would have read the play virtually with everybody first, done virtual table work with everybody like we do in live in-person theater, then rehearse the scenes a number of times, and gone deep into given circumstances, character portrayal, and relationship. We didn’t have a chance to do any of that like we normally do in the theater because of the actors’ schedules. They were awfully hard to get together at the same time. I prepared a color-coded shooting script so that all actors would know what stage direction narrations to hold for. I included color-coded notes for actors as well as notes for visual and audio dynamics. I sent character breakdowns to the cast, some character notes, my director’s ruminations on the script, my handle and take on the play. I also sent the cast the play’s story events to help them understand what was happening in each scene. To compensate for the lack of having time to do table work, I sent all of what I just mentioned to them in advance. Your 30-minute dramaturgical presentation in advance to the cast was foundationally important in providing historical data and context, and I thank you with deep gratitude. And, the acting company came in prepared. They are such fantastic actors anyway, such professionals, they came in ready.

The other challenge was in the editing process. Editing was meticulous and time-consuming. We also ran out of editing time and didn’t do as much of it as we wanted. We didn’t get a chance to check it thoroughly in the way that we wanted, so there were some glitches. We were learning a lot as we went along. So, Zoom theater is like in-person theater in a way, but it’s not in other ways. It’s kind of similar, but not similar. There are new things to contend with. You have to do things a little differently. I learned that there is this thing called exporting and rendering, which is computer talk. You record something, and before you can show it to the world, you have to export it and there is a time-consuming rendering process. It took 14 hours each time to render the full-length video of the show on Nina’s personal five-year-old Mac laptop. Because she had only one laptop, she couldn’t work on new parts while rendering the video on her only laptop. We learned that in the future, editing would benefit from having two computers with high-powered computing capacity and a lot of RAM, so that one can render material while editing work can proceed on another laptop. We learned a lot by doing. It was like jumping into the deep end of the pool. But I was able to avoid many of the things I didn’t like seeing in other examples of Zoom theater.

HS: While I was attending the virtual performance of The Living, I mean viewing the final recording, I felt like you as a director created a virtual black box theater just with actors in and no stage props like empty space, empty black box space. While seeing the actors’ faces moving around, I felt like they were moving apart from each other in empty space. I thought that was a part of your aesthetic creation in Zoom theater. It was quite impressive.

BSA: Thank you for that comment. As stated in the play’s stage directions early on, none of the actors, none of the characters touch except at the very very end of the play. They are all in isolation. Londoners back in 1665 were doing their version of social distancing. Nobody would touch each other because they were afraid of getting infected. The aesthetic look that we came up with was diamonds of characters isolated in a sea of blackness emotionally and metaphorically. Images of emptiness and absence run all through the play. The aesthetic choice we came up with seemed to be reinforced by what is in the play about characters who take great pains not to touch each other, to work together but apart. Anthony mentioned that he wouldn’t be happy if directors ignored the physical separation he built into the play.

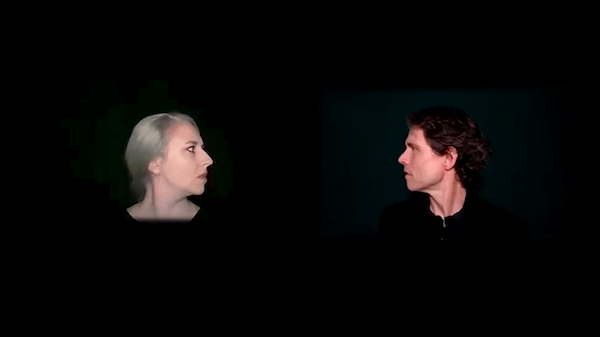

Samantha Richert and Lewis D. Wheeler in the Zoom theater production of The Living.

HS: You accomplished such a great representation of distance in virtual space. Did you get any suggestions from the actors regarding how to read the lines or any personal interpretations of the text? If yes, how did these suggestions and interpretations impact your virtual directing?

BSA: Actors can save a director from him or herself with a smart idea that the director didn’t think of. That happened several times in mounting The Living. For example, we had a complicated scene with about seven people on the screen. We had to figure out how to convey people entering and exiting a virtual room. It was really confusing and what we had been doing wasn’t working. One of the actors made a suggestion, I made the change, and it worked much better. He was absolutely right. I had several suggestions from the cast like that, even with the stage direction narration. There were some passages that I intended narrator Marya Lowry to read, but we found out we didn’t need to because the action on screen took care of it, and hearing it would have gotten in the way.

A couple of times, we added narration to make the story clear for the viewers. We did little tweaks like that. We were also working with a technique that I discovered through experimenting with one of our actors in advance of the actual recordings. Actor Lewis D. Wheeler and his partner, Amanda Collins, were very generous with their time as we worked out a technique to enhance the audiences’ viewing experience by what the actors do with their eyes. All the actors had their scripts on the screen that each could scroll individually because nobody was off book. Every word spoken was read. But we didn’t want the viewer to see actors look at the script and then move their head and eyes to an on-screen scene partner because in both instances, the viewer cannot see directly into the eyes of the actors. I wanted to minimize the extraneous head and eye movement and give viewers direct contact with the eyes of the actors. I also wanted to disguise the fact that the actors were reading text.

I chose to have all the actors hide their self-view and hide the view of their scene partners on screen and deliver all of their lines directly into camera light dot, with them imagining that they were speaking to their scene partner(s) in that camera light dot, using their actor’s imagination to speak to living, breathing scene partners whom they were not really seeing but were imaging in their imagination. When actors move in and out of looking into the camera directly, it is disconnecting for the viewer. So, I had the actors grab a line from the script positioned on the screen as close to the camera light dot as possible and give the line directly into the camera. All the actors had to look at their on-screen script while recording was taking place. They had to pick up cues about their scene partners through hearing their voices.

This does an interesting thing for the viewing audience once the editing is completed and all scene partners are shown on screen. The viewer thinks that the actors are looking at each other when they’re really not. I had this confirmed by a Los Angeles colleague who asked how we did The Living. He said he really liked the way I had the actors looking at each other. I said, no, they looked directly into the camera on their laptops all the way through the play except for the very, very last moment of the play when the character John Graunt helps the character Sarah Chandler to stand. This is also the only time in the play that the playwright allows any characters to touch each other. It’s at the very end of the story – a magnanimous, beautiful, poetic statement of a human being helping another human being during a crisis. They turned toward each other on the screen and then began to move toward each other slowly to approximate touching.

This technique of grabbing lines from the on-screen script and delivering those lines directly into the camera is an immediate connection for viewers that somehow, through a kind of Jedi Jiu-jitsu mind phenomenon, makes the viewing audience “think” that characters are talking to and looking at each other. But the actors were not really looking at each other.

Ed Hoopman – upper left; clockwise from lower left: Lewis D. Wheeler, Diego Arciniegas, Ken Cheeseman, and Michael Tow, in the Zoom theater production of The Living.

HS: I think The Living’s final recording has some performance aspects even though we see it on-screen because the actors were still virtually performing behind the screen. That’s why I prefer saying it is a virtual performance, and what you created is more than a presentation. It wasn’t just simply presenting something to the virtual audience. In the postperformance conversation on Zoom, we had about 60 people who were excited about seeing The Living on-screen. And, they were really excited about your work, and the way you bought the audience, artists, and creative team together to produce the piece. How did you feel and what did you think when everybody — the audience, playwright, director, creative team, and the actors — were together in virtual space?

BSA: I was thrilled. But I knew this was, in a way, a risk because I was dealing with new territory. Although many of the actors have done lots of Zoom readings in the past, this was my first time organizing, directing, and producing a piece of virtual theater for the public. I was a little nervous about it. It is going to take me a little while to get my mind around the fact that it was a production that was performative, that we recorded live, edited it, and released it publicly. I should just give over to it and say it was a virtual performance. I think that gives the director, the actors, and creative team more of a professional concept.

HS: You also managed to bring audience members together even though they weren’t sitting together in the auditorium.

BSA: We managed to bring many aspects of theater together, like the audience, director, playwright, actors, stage manager, composer, and dramaturge. I was glad we did it. Many people would describe our postproduction chat as a talk-back on Zoom. They saw the behind-the-scenes collaborators during the talk-back session. The term I prefer to use is “Folk Thought Session.” That is a term we use at the Rites and Reason Theatre Company at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1970, I was a founding student member of this now 50-year-old theater company that is still alive and still producing. At the Rites and Reason Theatre Company, we called talk-back sessions, “Folk Thought Sessions” because the folks in the house are thinking, expressing, and sharing. What was great about what we did with The Living was that we had audiences viewing from all over the country: Los Angeles, Oakland, Washington, DC, New York City, and elsewhere.

We had the behind-the-scenes people there: digitaltTechnical designer and video editor Nina Groom; stage manager Becca Freifeld; Dewey Dellay, our brilliant genius composer of original music and sound effects; Bill Marx, our generous underwriting sponsor and editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse online arts magazine; playwright Anthony Clarvoe; yourself as dramaturge. We were all there, and I could not have done any of this without them. Often in live in-person theater, you do not see the behind-the-scene people who contribute to the production’s success. I was pleased to see how galvanized the viewing audience was during our postviewing discussion.

But I give the most credit to the play. The Living is an astounding piece of theater that is so relevant now. One of the things in the play that particularly captured the audience was the character of John Graunt, who speaks to the future. In his opening statement at the top of the play and from his vantage point in the middle of the 1665 bubonic plague in London, he speaks to a future he will never meet. He invites that future to judge what Londoners did in 1665 and maybe, if we are smart, we could learn something from it.

When Anthony wrote The Living 29 years ago, how did he know that we would need his words in 2020, during COVID-19, our version of the bubonic plague? Anthony had it right in his interview that I alluded to: this is an example of our human ancestors speaking to us, trying to give us some help. The virtual audience saw our current Coronavirus pandemic crisis through the lens of a historical episode. The spectrum of human responses to the 1665 London plague was identical to what we are doing right now with our plague — the good, the bad, the ugly, and everything in between. You can see that happening in our lives right now as we are globally dealing with this COVID-19 pandemic. I think our audiences were hooked into that. Through this play, they were given a chance to reflect on our own behavior as a human society in this current COVID-19 pandemic, and that was what I was hoping for. By putting a virtual production of The Living out there to the world as a COVID-19 response from the Boston theater community, I hoped it would help us all make sense of and cope with this devastating pandemic that we are going through now. We just did it virtually. This is the power of virtual theater now.

HS: When I interviewed Anthony about the play, he said The Living is a socially relevant play. As a director, did you also intend to produce a socially relevant virtual performance on Zoom? Did Zoom allow you to manifest the social aspects of The Living?

BSA: Yes. Our society is separated, isolated, polarized, and apart from each other because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fractured times we live in. Producing The Living virtually allowed us to stay healthy while working together, united on screen to create a work of virtual art that connected people virtually when we streamed it. The Living gives us much food for thought.

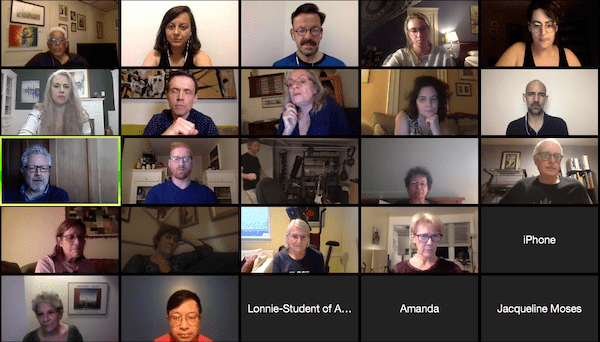

The postperformance discussion for the Zoom Theatre production of The Living.

HS: What have we learned from The Living?

BSA: I go back to the biblical scripture, Ecclesiastes chapter 4, verse 10, that is in the play’s foreword: “For if they fall, the one will lift up his fellow: but woe to him that is alone when he falleth; for he hath not another to help him up.” Given both the current COVID-19 pandemic and the pandemic of racism – the other major scourge of our time –that has been illuminated by the police murder of George Floyd echoing so many other abuses of violent police power, what should we as a human society do in response to all of that?

The hope that I see is contained in The Living. For instance, the work the character Dr. Harman did staying in London where the plague was most rampant instead of escaping to the country like the cowardly king and his court did. The king leaving behind his fellow humankind to rot in painful deaths without offering sufficient help is reminiscent of our federal government not helping enough in our current crisis. The character of Sarah dedicates herself to helping others after the plague wiped out her family.

I have had a really hard couple of days lately. We watched the storm troopers cleared out Washington, DC’s Lafayette Square so that the President could do that photo op in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church. That video footage ended up in campaign ads with music underneath with the President strolling like some dictator. I am worried. What will be left of American democracy as it unravels before our very eyes in daily television installments?

The nation is on a knife’s edge now, and it can go either way. I do not trust that guy, the President. I do not trust this administration. I do not trust the dark forces that would, in so many ways, put a knee on our necks. It can go either way. Fascism is staring us in the face right now, we are seeing it take root right now. And so, the American citizenry is rising up in the streets. We will see if we can win it. We can win the day if we can push back those dark forces and if we can get enough allies to put pressure on enough levers of power to redirect it to something more humane.

We have a national leader who is accelerating the dissolution of those lofty Democratic pronouncements that are in the enabling legislation of this country: the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, the Constitution, aspirations never fully realized. But I hold onto hope that one day we can move toward a more perfect union and achieve it. Our country has been marching in that direction in fits and starts. Dark forces are trying to push that progress back. I battle with optimism and hope and despair and rage and anger and everything in between.

You see a spectrum of human responses to a public health crisis in The Living from the heroic to the ignoble. We must constantly remind ourselves of what the better way forward is. We can see glimpses of it. We see what the character John Graunt did with Sarah at the very end of The Living – to actually touch her, to lift her up, knowing that it may infect him. We do not know what happened to him or Sarah because the play ends at that point. But Graunt made the supreme human gesture, which is what I think is the inherent plea inside this play. The appeal at the core of The Living is to go the way of John Graunt and Dr. Harman and Sarah Chandler.

A play like The Living pricks the conscience of the country. It is the reason I wanted to produce and direct it. I wanted to contribute something while in COVID lockdown. I wanted to give my fellow artists something to do and to raise money for the excellent and essential Theatre Community Benevolent Fund, an organization that gives money to theater workers faced with catastrophic occurrences.

HS: How do you plan to progress this project?

BSA: I would love to direct it live and in-person somewhere, anywhere in the world. I am available. Also, my creative team and I are reediting the video to try to fix the glitches and make it prime-time ready for potential future broadcast, hopefully.

HS: Thank you, Benny. It was my great pleasure working with you in the virtual performance of The Living on Zoom. Our conversation also shows how important it was to explore The Living in the time of COVID-19.

Hanife Schulte is an international and interdisciplinary scholar and practitioner of theatre and performance studies. Schulte researches how experimental theatre and performance arts respond to cultural, political, and social issues in Germany, Turkey, and the US. She practices theatre in serving as an assistant director and dramaturg. Schulte was a fellow at the Mellon School of Theater and Performance Research at Harvard University in 2019. Schulte’s peer-reviewed article has appeared in the February 2020 issue of New Theatre Quarterly published by Cambridge University Press.

Tagged: Anthony Clarvoe, Benny Sato Ambush, Hanife Schulte.