Film Review: The Soulful Comic Legacy of John Belushi

By David Stewart

Belushi is a warts-and-all look at one of comedy’s raging bulls.

Belushi, directed by R.J. Cutler. Coming to Showtime on November 22.

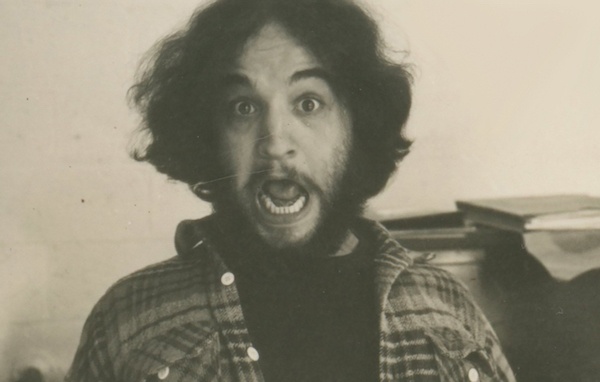

A young John Belushi in Belushi. Photo: Showtime

John Belushi was a driving force in physical comedy, idolized on every college dorm wall as the anarchic Bluto from Animal House or the cartwheeling Joliet Jake from The Blues Brothers. His larger-than-life comedic antics and rock and roll persona served as the ballast for Sam Kinison and Chris Farley. Like the pair that he inspired, Belushi couldn’t slack his taste for excess, which led to an early grave at 33 from a drug overdose. Belushi’s life and musings are the focus of R.J. Cutler’s latest documentary, which premiered this past weekend at AFI FEST and is coming to Showtime on November 22. Drawing on audio interviews with friends (Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, Carrie Fisher), adversaries (Lorne Michaels), and family — along with letters by Belushi read by Saturday Night Live alumnus Bill Hader — Belushi stands as a warts-and-all look at one of comedy’s raging bulls.

Beyond the cavalcade of memorable and never-before-seen footage showing Belushi in his prime, there are anecdotes and memories of the performer presented through animated sequences by Robert Valley, known for his work with Gorillaz. These scenes are surprisingly tender: an animated Belushi mimics his farcical hero, Jonathan Winters, in his childhood bedroom; or his widow, Judy, recalls how he wanted to devote his life to making people laugh after attending a performance at Chicago’s Second City Theatre. When Dan Aykroyd enters the picture, his stories of him and John at their most mischievous add a heartfelt, fraternal connection that closely mirrors the rollicking comradeship of the Blues Brothers, as when the pair drive cross country listening to the Allman Brothers and Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” on a CB radio.

Belushi’s no-holds-barred energy inevitably made him difficult to work with; his defiant and willful attitude at Saturday Night Live singled out executive producer Lorne Michaels. One writer recalls Belushi going into Michaels’s office after he left just so the comedian could use his table for snorting cocaine. Even Jane Curtin chimes in about how her fellow Not-Ready-for-Primetime-Player was often too much to handle, both during rehearsals and when the cameras were rolling. The acceptance of a bacchanalian environment at Thirty Rockefeller was in full swing in the late ’70s, but Belushi, unlike others, mowed down every stop sign on his road to excess.

In his previous films, R.J. Cutler has tackled subjects from politics (The World According to Dick Cheney) to high school (American High). The director approaches Belushi as a revealing cultural figurehead, a casualty of the raucous party atmosphere in Post-Watergate America long before “Just Say No!” became part of the ’80s antidrug lexicon. One of the most heart-wrenching sequences in the film is when Hader’s narration of Belushi’s letters gives way to the defeatist prose the performer wrote just before his death, followed by footage of police and press gathered outside the Chateau Marmont Hotel. After seeing Belushi, thinking of the comic’s celebrated take on Joe Cocker’s version of The Beatles’ “With A Little Help From My Friends” becomes a bittersweet experience — the contorted gestures, the soulful voice, and the heedless rush to extinction.

David Stewart is a Professor of Film and Media Studies at Plymouth State University. Along with teaching, he is a documentary researcher and contributing writer The Film Stage and PleaseKillMe.com. His film credits include Amy Scott’s documentary Hal and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl. He lives outside of Boston with his family and beloved Fender acoustic, Nadine.

Tagged: Belushi, David Stewart, documentary, John Belushi, R.J. Cutler