Opera Album Review: Offenbach in a Spanish Mood, in a Top-notch First Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Bravo to the Bru Zane folks for this latest triumph! I encourage opera lovers to get to know this treasurable Spanish (or faux-Spanish) work by the pioneering master of 19th-century operetta.

Jacques Offenbach: Maitre Péronilla (operetta)

Anaïs Constans (Manoëla), Véronique Gens (Léona); Antoinette Dennefeld (Frimouskino); Chantal Santon-Jeffery (Alvarès), Eric Huchet (Péronilla), Tasssis Christoyannis (Ripardos).

French Radio Chorus, French National Orchestra, conducted by Markus Poschner.

Bru Zane 1039 [2 CDs] 101 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

French opera has a tough time in the non-Francophone world. Over the past century or more, only a handful of French-language works (such as Carmen and Faust) have managed to get performed as frequently as the best-known Italian-language works (such as Don Giovanni, La traviata, and Tosca).

Since 2009, the Center for French Romantic Music, a well-funded scholarly institute located in the Palazzetto Bru Zane in Venice, has been laboring intensively to help bring major (and interesting minor) French operas to the world’s attention. The 23rd and latest recording that they have released, in a first-rate performance, is Maître Péronilla, a little-known but delightful operetta (or opéra-bouffe) by Jacques Offenbach, best known among opera lovers for such treasurable works as La vie parisienne, La Périchole, and Les contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann).

For each of the releases in the Center’s “French Opera” series, the scholars at the Center prepare or commission a score (and performing parts) and arrange for the work to be recorded (usually at, or shortly before or after, a public performance). Each recording comes accompanied by a small-format book that offers first-rate essays, carefully chosen illustrations, and the full sung text (plus, if relevant, any spoken dialogue).

The first dozen or so releases bore the imprint “Ediciones Singulares”: this was the name of the Spain-based publisher of the book that came with the CDs. Recent releases are labeled, more clearly, as “Bru Zane.” (The Center also produces two other CD series: “Portraits” of individual composers; and “Prix de Rome,” which offers early works in the composing career of such notable figures as Gounod and Debussy.)

I have hailed numerous items in the series, here or in some other venue (e.g., American Record Guide), including operas by Méhul, Catel, Spontini, Hérold, Halévy, Félicien David, Saint-Saëns, Gounod, Lalo (with co-composer Coquard), Benjamin Godard, and Messager’s operetta Les p’tites Michu.

Recent items in the series included the previously unrecorded first version of Gounod’s Faust and an all-French cast doing Offenbach’s operetta La Périchole in fine style (a work that has some Spanish flavor, being set in colonial Peru). I am excited that the Bru Zane folks have begun adding operettas to the list because that genre—especially its French branch—is almost systematically neglected by theaters and record companies nowadays, even in France. Also, what recordings do manage to get made often involve international singers who are not able to capture the insouciant wit of the extensive spoken dialogue.

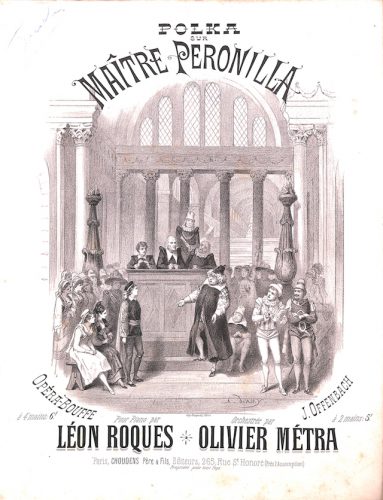

The present Maître Péronilla (1878) seems never to have been recorded in its entirety before. An accomplished and spirited but faintly recorded performance on YouTube, performers unnamed, is 25 minutes shorter, despite containing much spoken dialogue. (One advantage: the video screen shows the piano-vocal score, coordinated page by page with the audio.)

Maître Péronilla turns out to be delightful. Its witty libretto was written, or co-written, by Offenbach. One of the essays in the accompanying book proposes that the work has suffered from its uninformative title and suggests that something like Manoëla and Her Two Husbands would have helped it more. I’d say a bigger weakness, from the standpoint of modern-day theaters, is that not one but two of the six leading roles (Frimouskino and Alvarès) are trouser parts.

The plot premise is amusing and, a rarity among comic operas, not overly complicated. Manoëla, daughter of a chocolate manufacturer, is forced to marry (in a civil ceremony) a wealthy old nobleman whom she detests (his role is small, not listed above), whereas she is in love with the young music teacher Alvarès. In the dark chapel for the second (church) wedding, Alvarès, encouraged by two accomplices (Ripardos and Frimouskino), sneakily signs the second wedding contract, which was intended for the older man. The young lovers, now officially married in the eyes of the religious authorities, attempt to run off together, but the local police lock everybody up and arrange a trial to determine which of the two men is the real husband. At the end, it becomes known that Alvarès’s accomplices had done a previous switcheroo, substituting, on the civil marriage contract, the name of Léona—Manoëla’s maiden aunt—for that of Manoéla. (Surely it is not by chance that the two names contain many of the same letters, rearranged.) The two older people pair up, thus satisfying the forces of law, the young pair remain together, and everyone repeats the “Malaguenia” that Alvarès had sung at the wedding celebration.

Offenbach’s music for the work contains plentiful numbers in a very engaging Spanish (or pseudo-Spanish) style. I had not realized how extensively Offenbach used ethnic “local color” (aside from the world-renowned Barcarolle in the Venice act of The Tales of Hoffmann). Other numbers match the particular dramatic situation: for example, a sonorous wedding chorus, and a military song for the soldier Ripardos (the elder of Alvarès’s two accomplices).

Most of the solos are simple strophic ballads and such, with a refrain, and a few could probably be removed with little loss, as could a somewhat pointless short duet for the two witnesses at the church wedding. (Or maybe it could be made very entertaining on stage, through canny gesturing and funny voices.) But far more of the solos are utterly delectable, such as Frimouskino’s rondeau in Act 2: an account of his hasty journey to rejoin the others outside of Paris. The number requires virtuosic rapid patter, and gets it here.

The course of the music is rarely predictable, especially in larger ensembles (such as the Act 1 Trio), act-finales, and the orchestral numbers (such as the prelude to Act 2). The orchestration is often intriguingly varied, especially when, as here, played with alertness, vigor, and a fine cantabile line. The Orchestre National de France and the Radio France chorus are superb. Balances throughout are expertly handled by the engineers.

The solo vocalists are nearly all first-rate, as one would expect from names as distinguished as those of Véronique Gens and Tassis Christoyannis, both of whom I have repeatedly praised in reviews (see David, Gounod, and Saint-Saëns above; also Christoyannis in three separate CD albums of songs by, respectively, David, Saint-Saëns, and Lalo). Gens shows here a gift for comic exaggeration that her normally placid, thoughtful demeanor would not have led me to expect. Christoyannis’s French gets better year by year (he comes from Greece), though I worry a little that his emphatic acting-through-the-voice is beginning to fray the special velvet of his sound. Eric Huchet fully realizes the spoken and singing challenges of the title role (Manoëla’s father): I had expressed great admiration for his performances in operas of Hérold and Halévy (see above), and am no less impressed here.

Santon-Jeffery is a somewhat weak link, suffering from a slow throb and hitting long notes a trifle under pitch. She comes across as somewhat blank and dutiful in her solo songs, but perks up in spoken dialogue and in ensemble numbers. (This is a bit odd. I’m more accustomed to singers being dutiful but anonymous in ensembles and then becoming quite specific and imaginative in their big arias.)

You’ll need to keep remembering that Frimouskino and Alvarès are youngish males, because the singers don’t try to make their voices sound husky (nor do I think they should have tried). Antoinette Dennefeld (the Frimouskino) was new to me and performs marvelously here. I look forward to hearing her in future roles, and that goes for the opera’s main soprano, likewise a fresh discovery: Anaïs Constans.

In short, bravo to the Bru Zane folks for this latest triumph! I encourage opera lovers to get to know this treasurable Spanish (or faux-Spanish) work by the pioneering master of 19th-century operetta. A two-minute video trailer gives a sense of the vocal splendor and variety on display.:

One can hear the beginning of each track here. The entire recording can be enjoyed for free on YouTube, broken into dozens of separate tracks. The full recording can be heard (continuously) through Spotify or other streaming services. One of these, Naxos Music Library (to which many libraries subscribe), lets you download the excellent 162-page book, which contains the humor-filled libretto in French. (The translations of the essays and the libretto are quite good.)

In future releases, I hope that the Bru Zane folks will provide a more detailed synopsis (including track numbers or at least a brief indication of what motivates each musical number). And please identify plainly, in the English version, when a character is a trouser role! After all, a “clerk” can be male or female, whereas, in French “le clerc” is crystal clear.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Bru Zane, French National Orchestra, French Radio Chorus, Jacques-Offenbach, Maître Péronilla, operetta