Opera Album Review: A Version of One of Rossini’s Finest — Recorded on CD for the First Time

By Ralph P. Locke

Rossini’s Zelmira is a powerhouse opera that features two coloratura tenors and equally demanding roles for soprano and mezzo.

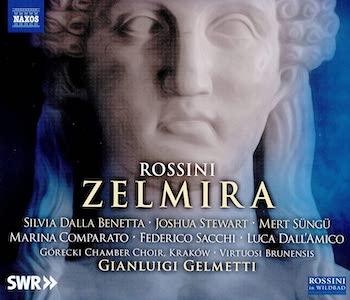

Gioachino Rossini: Zelmira (Paris, 1826 version)

Silvia Dalla Benetta (Zelmira), Marina Comparato (Emma), Mert Süngü (Ilo), Joshua Stewart (Antenore), Leucippo (Luca Dall’Amico), Federico Sacchi (Polidoro).

Virtuosi Brunensis and Gorecki Chamber Choir, conducted by Gianluigi Gelmetti.

Naxos 8.660468-70 [3 CDs] 175 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

The flow of highly capable recordings from the Rossini in Wildbad Festival (in Germany’s Black Forest region) continues apace, enabling us to understand, especially, why his serious operas were so widely adored in the nineteenth century as well as how influential they were on Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi. I wrote enthusiastically here about Adelaide di Borgogna and Sigismondo and, separately, about Eduardo e Cristina. In reviews for American Record Guide I was likewise enthusiastic about Demetrio e Polibio, Bianca e Falliero, Aureliano in Palmira, and the immense Maometto II (Rossini’s response to the Greek war of independence from Ottoman Turkey).

The flow of highly capable recordings from the Rossini in Wildbad Festival (in Germany’s Black Forest region) continues apace, enabling us to understand, especially, why his serious operas were so widely adored in the nineteenth century as well as how influential they were on Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi. I wrote enthusiastically here about Adelaide di Borgogna and Sigismondo and, separately, about Eduardo e Cristina. In reviews for American Record Guide I was likewise enthusiastic about Demetrio e Polibio, Bianca e Falliero, Aureliano in Palmira, and the immense Maometto II (Rossini’s response to the Greek war of independence from Ottoman Turkey).

Zelmira is heard here in a 2018 concert performance or conflation of several performances. (The dates given by Naxos are wrong.) The opera was the last that Rossini composed during his years heading the theater in Naples (1815-22). It shows many of the traits that record collectors know from some of Rossini’s other Naples serious operas (e.g., Otello, not to be confused with Verdi’s tumultuous masterpiece of a half-century later), such as fewer solo arias and more duets and larger ensembles than was Rossini’s norm earlier (e.g., in Tancredi). I fell in love with many numbers, such as the trio, early on, for soprano, contralto, and bass — that is, Zelmira, Emma and Polidoro — and the whole long Act 1 finale, which includes extensive and important passages for chorus. Best of all, perhaps, is the big quintet in the middle of Act 2, with several singers churning out coloratura passages simultaneously, for a thrilling effect. Many musical numbers begin with a broad-framed orchestral prelude, sometimes intriguingly chromatic in harmony.

The orchestration is varied and imaginative, with all kinds of inventive string figurations and solo-wind contributions. An exquisite shortish duet for Zelmira and Emma is accompanied by nothing but a harp and an English horn. The brass instruments get quite a workout as well, including in several passages that invoke military power through march-like rhythms. All of this shows Rossini moving firmly away from the style and manner of the comic operas best known today (e.g., Barber of Seville) and toward the dramatically intense works of Donizetti and early Verdi.

Yet Rossini and his librettist also show a deep awareness of longstanding Italian operatic traditions: the chorus of soldiers seeking the murderer of Azorre (and holding an urn with his ashes) is written in a rhythm derived from the quinario sdrucciolo of Italian versification (six syllables with accent on the fourth syllable). This verse meter and its corresponding musical rhythm (triple meter, including a dotted figure) occur in many Baroque and Classic operatic scenes that invoke divine or supernatural powers, e.g., the chorus of the furies and demons of the underworld in Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice. In the present case, the quasi-ritualistic choral entry occurs before, and also motivates, the hectic final section of the Quintet, in which the characters express (in asides!) their various intense reactions to the soldiers’ accusations and threats.

The plot is typical of Rossini serious operas in being complicated but ending happily. The excellent synopsis here fills five columns of smallish type. I had to read it several times in order to absorb it. Briefly, King Polidoro of Lesbos has been deposed by Azorre and is in hiding. His daughter Zelmira and her handmaiden Emma know where he is. Zelmira’s husband, Prince Ilo of Troy (one of the opera’s two big tenor roles), returns from battle, only to learn that Antenore (the other tenor) is now on the throne, having murdered the usurper Azorre. Big bad Antenore spreads the word that Zelmira killed Azorre. The nasty courtier Leucippo attempts to kill Ilo, and then accuses Zelmira of having been the one who was trying to do it. (She had grabbed the dagger from Leucippo’s hand, and the evil wretch turned this to his advantage.) Zelmira is imprisoned, but the evildoers let her out in order to follow her (without her realizing it) to where her father, the deposed king, is hiding. Father and daughter are now both arrested. Antenore and Leucippo try to kill Polidoro, but Zelmira, drawing a dagger (aha, she kept it!), defends him. Prince Ilo and the forces of good arrive. Having learned (earlier) from Polidoro that Zelmira was loyal, he arrests the evildoers, and puts the rightful king back onto the throne. (I left out a lot, but you get the gist.)

Tenor Joshua Stewart. Photo: Joshua Stewart.com

There have been two commercial recordings (plus some pirated ones with famous sopranos), of which the better is the 2003 Opera Rara, starring Elizabeth Futral, Bruce Ford, and Antonino Siragusa, conducted by Maurizio Benini. (The opera authority Charles Parsons reviewed it in American Record Guide: January/February 2005.) Richard Sininger found many strengths in the 1989 Erato recording featuring Cecilia Gasdia, Chris Merritt, and William Matteuzzi, conducted by Claudio Scimone (ARG March/April 2014). The present recording has the advantage of using the new critical edition (by Helen Greenwald and Kathleen Kuzmick Hansell) and presenting — for the first time on CD — the Paris version of 1826, which reworks as an ensemble number the highly florid solo aria for Zelmira that originally ended the opera and instead gives her more to do in the prison scene earlier in the act. For some of the new music, Rossini reused material from another of his serious operas, Ermione.

In addition, the recording incorporates, as did the Erato and the Opera Rara, a chorus-and-aria scene for Zelmira’s handmaiden Emma that Rossini added for the opera’s important production in Vienna (soon after the 1822 Naples premiere). The aria does nothing to advance the plot, but the music is gorgeous and is festooned with a glittering concertante harp part.

The Paris version of the final scenes makes the new recording an essential purchase for devoted collectors of the bel canto repertory (but see my closing remark about a DVD version). The orchestra and chorus are bright and well controlled (as always in Wildbad), except for a clumsy and ill-tuned English horn. Gelmetti’s conducting is mostly up to his usual high standard. I found the cabaletta of the big Zelmira-Ilo duet to be too fast, but the audience disagrees with me. The voices are very clearly miked; the orchestra is slightly softer, perhaps in order to minimize noise from the auditorium—a practical solution when recording a live performance.

The singing is generally impressive. It helps that the tenors are easy to tell apart. I was pleasantly startled by Joshua Stewart (from New Orleans), whom I had never encountered before. He has a voice of burnished metal, with clean projection from first moment to last. Mert Süngü (from Turkey, with further training in Bologna) sings sweetly when soft, but insists on delivering many high-lying passages in full voice, despite all evidence showing that Rossini-era tenors used some kind of falsetto or head voice in such situations. (Alas, this is true of almost all Rossini tenors today.) His coloratura is sometimes smeared. I wonder if his insistence on full-voice high notes has coarsened his vocal production and reduced his flexibility. Still, he makes a bright, attention-getting sound, conveying plenty of confidence and charisma. And he improves as the opera progresses.

Silvia Dalla Benetta and Marina Comparato (as Zelmira and Emma) are fine, though they wobble a bit at times. Dalla Benetta’s voice firms up in the later scenes, to compelling effect.

Luca Dall’Amico and Federico Sacchi have a wobble as well, the latter only in the lower part of his voice. His high range is marvelously well supported and intriguingly hollow-sounding, a bit like the great Boris Christoff: perfect for an aged, deposed ruler.

The Opera Rara and Erato recordings offer more consistently poised singing, cleaner coloratura, and much less wobble, somewhat richer orchestral sonority (because of closer miking?), but also often less excitement. (Bernarda Fink, on Opera Rara, is probably the best Emma so far.) The Erato, which may have been somewhat trimmed (it is twenty minutes shorter and fits onto two CDs), is out of print. It was made in a studio after an unstaged performance and offered a libretto in four languages (though full of typos). The live performance that preceded it can be heard on YouTube and greatly enjoyed, despite somewhat distant miking throughout. Two of the main singers — Cecilia Gasdia and Chris Merritt — can also be heard, in better sound, in a dress rehearsal from a Rome production a year later; Rockwell Blake here replaces William Matteuzzi as Antenore.

The Opera Rara, recorded during an unstaged performance, is still available on disc and contains a libretto in Italian and English. (This otherwise so admirable firm has unfortunately let some of their other recordings go out of print as CDs, keeping them available only as digital downloads.) Like the new recording, it is available on various streaming services and, for free as a series of separate “tracks,” on YouTube.

The Naxos recording (which is also available through streaming services such as Spotify) conveys well the excitement of a performance. (You can hear the beginning of each track here. Each one is also currently available at YouTube, as a separate item.) Each number is followed by enthusiastic applause — tightly edited, I’m glad to say. It offers a libretto online (and the fine essay and plot synopsis, both by Reto Müller), but the libretto is in Italian only. Gosh, even the cheesy-looking pirated LP set with Virginia Zeani contained a bilingual libretto! On the plus side, the fact that Naxos has posted the essay, synopsis, and libretto online (open access) will help someone listening to any of the recordings — including people who no longer purchase CDs but instead stream their music and thus do not have access to Naxos’s physical booklet.

I should also mention a DVD of the opera, deriving from a staged production at the Rossini Festival in Pesaro (2009). It features the superb tenore di grazia Juan-Diego Flórez as Prince Ilo, Gregory Kunde as Antenore, and Kate Aldrich as Zelmira. The excerpts that I’ve watched (in the YouTube upload) are stupendous, despite the distracting World War II costumes. Flórez takes high notes at full volume but more securely than anybody else alive. The production was the first to use the critical edition of the Paris 1826 version.

I urge all lovers of bel canto opera to get to know this astounding opera, one way or the other. I recently heard a radio broadcast of a concert performance of it (by Washington Concert Opera) featuring tenor Lawrence Brownlee. (His studio recording of Ilo’s aria “Terra amica” is startlingly wonderful.) The work is slowly making its way back into performance. It belongs there: on the concert stage but also in staged performances.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Gianluigi Gelmetti, Gioachino Rossini, Gorecki Chamber Choir, Naxos, Ralph Locke, Virtuosi Brunensis