Book Interview: Talking to BrownMark about “Life in the Purple Kingdom”

By Blake Maddux

Front and center in this memoir are BrownMark’s efforts to reconcile his resentment and gratitude toward the man who both sold him short and afforded him the “opportunity of a lifetime.”

My Life in the Purple Kingdom by BrownMark with Cynthia M. Uhrich. Foreword by Questlove. University of Minnesota Press, 144 pages, $22.95.

Click here to buy at Bookshop.

BrownMark will discuss My Life in the Purple Kingdom at a virtual launch event – 6 p.m. (Central), Monday, September 28. To register for the event: z.umn.edu/pkregister. Journalist Touré will moderate a Q&A with the author. Copies of the book will be available for online purchase during the event. The event is hosted by the University of Minnesota Press.

The artist best known as Prince certainly wasn’t a nobody when bassist Mark Brown joined his band in 1981. However, it is unlikely that many music industry insiders foresaw that he would emerge as one of the most iridescent stars in the pop music galaxy three years later.

The artist best known as Prince certainly wasn’t a nobody when bassist Mark Brown joined his band in 1981. However, it is unlikely that many music industry insiders foresaw that he would emerge as one of the most iridescent stars in the pop music galaxy three years later.

Dubbed “BrownMark” by Prince, the starstruck 19-year-old was brimming with energy, optimism, and confidence when he came aboard for a voyage that would include credits on four albums — 1999, Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day, and Parade — that to date have sold a total of more than 20 million copies in the United States.

Referring to the first time he saw Prince somewhat up close and in person, Brown said in a recent phone interview with The Arts Fuse, “I cooked him pancakes and three years later I’m sitting in the rehearsal room with him jamming.”

BrownMark’s natural ability and boundless ambition could not be sated, even in the employ of such a domineering musical auteur. In 1983, immediately after Prince’s 1999 tour ended, he formed a side venture called Mazariti. That band might have had a signature tune of its own. But that possibility was foiled by Prince’s dogged unwillingness to relinquish the spotlight (literally and figuratively) to his theretofore unfailingly loyal bass player.

The 58-year-old musician, songwriter, and producer is now also an author thanks to the recent publication of My Life in the Purple Kingdom. In its 150-or-so pages, Brown guides the reader through a series of unlikely events that includes serendipitously discovering (someone else’s) bass guitar, performing in front of nearly 100,000 unmerciful Rolling Stones fans, and having his ability to afford a fancy automobile questioned. For all of its benefits, he learned in due time that “Being famous…is not for the faint of heart.”

Front and center, however, are BrownMark’s efforts to reconcile his resentment and gratitude toward the man who both sold him short and afforded him the “opportunity of a lifetime.” The book’s impact is simultaneously poignant and inspiring.

Brown, the father of two and grandfather of one (soon to be two), now lives in Atlanta. He is working on the sequel to My Life in the Purple Kingdom as well as a kids’ book that he describes as “a fantasy based on real-life things that happened” to him and his childhood friends. (“It gonna be kinda like a Harry Potter book,” he adds.)

The Arts Fuse: Had you always wanted to write a book about your time in The Revolution?

BrownMark: I started writing almost kind of like a therapy about 15 years ago. I started, stopped, started, stopped, you know. Before Prince passed away, I had told him I was writing it, and he just asked that I let him read it before I put it out to prepare him. Because he knows I tell it like it is and that we had a turbulent history. I think he was curious as to how much in depth I would go into that. I kept it pretty shallow, you know, ’cause the purpose is not for me to bash or anything like that. I’m telling a story from my angle. It’s not a Prince book, it’s a BrownMark book. It’s a book about a boy who grew up having this opportunity of a lifetime, and all the experiences that came with it. The dos and the don’ts. Any young kids coming into the marketplace or any people coming up that just need a boost of will power, this story will definitely give it to you.

AF: Did Prince get to read any of it before he died?

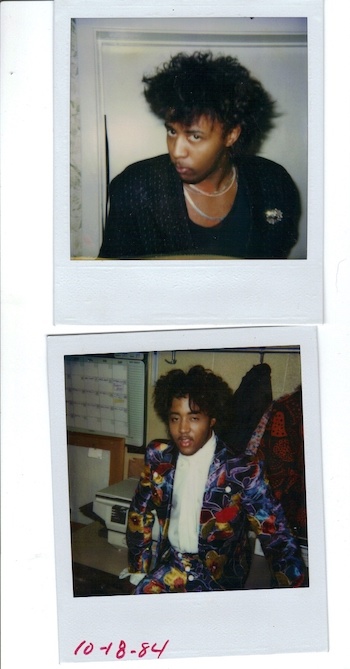

BrownMark on the Purple Rain Tour. Photo> Karen Krattinger.

BM: No. He passed away right when I was almost finished with it. He never got to see the completed transcript. Then I had to put it on hold because I just couldn’t think about it. Once I reentered the book a couple years after his passing, there was a lot of things that I wanted to change. I wanted to soften it a little bit. I didn’t want it to be too harsh. When he was alive it was easier for me to sock him in the gut. That’s kind of the relationship that we had. He was my big brother. We went back and forth like that and we were able to share our feeling and emotions with each other like that. So I wasn’t afraid to sock him in the gut! But now he’s passed away and I don’t need to tell some of this stuff.

AF: Was it indeed therapeutic to tell your story?

BM: Absolutely. Putting the words on the page released so much tension, so much build-up that I had. ‘Cause I gave the prime of my life to The Revolution. All of my career wants and aspirations, I put it aside for this. To come out on the other end of it kind of short-handed…. I was kind of angry about a lot of stuff, so I had to process that somehow. I would have nightmares 10 years later. To this day I still have nightmares about different scenarios. My therapist told me, “You should write down your feelings, write down the things that are troubling you.” So that’s what I did.

AF: You write in the fourth chapter, “The black community was so small I thought I was a world-renowned rock star!” Were you well-known enough in Minneapolis that Prince may have been at some of your shows?

BM: Oh, he was. He definitely was. We used to play at First Avenue, the local Elks lodge, the Nacirema Club. I was basically in the Chitlin’ Circuit, and he would always pop in. I knew it was him. You could see him standing in the corner, and he always had this big Afro. So I always knew he was watching us, I just didn’t know what for. You know, I thought maybe he was looking at the band to produce us or something.

AF: Did knowing that he was in the room make you nervous?

BM: Oh no. We would see him and we would just start showing off!

AF: What was it like to relate to Prince on a personal level?

BM: It’s interesting, because once he brings you into his family, he opens up and you see a whole different person. I met him as the rock star, auditioned with him as the rock star, but when he let me in, he became a brother. It was a whole different relationship, like, instantly. He’s picking me up in his car, he’s driving me around, he wants to know my opinion on this new song that he’s working on. But then when the rehearsals started, man… Now you’re not his friend anymore. Now it’s business. He was a strict bandleader and did not play around. He was a mean one! But it was good, because being a bandleader, that’s what it takes. I know that now, because I was a bandleader in Mazarati and many bands after that. You gotta be hard.

AF: Why do you think that Prince was so determined to keep you in his band despite the fact that he was often over-promising and under-delivering?

BM: That was one of the reasons why I needed the therapy. How do you make $100 million [on the Purple Rain tour] and not take care of your band? I couldn’t process that. A lot of fans say that we should be happy that we had the privilege. No, that’s some BS. He was happy he had the privilege to work with ME! I’m not trying to be arrogant, but c’mon. I could step up with him any day, any time, any place. I was a force to be reckoned with. I was no slouch. I knew what my abilities were, and so I didn’t understand what that was all about. Why are you trying to hold me down, man? He was like, “no, no we gotta help each other. We gotta stick together.” And I was like, “Well you’re not doing that! … Why don’t you just break us off a piece?”

Around ’85-’86 when I quit the band, he begged me to stay. I was gonna disrupt his momentum because I had helped develop that sound. I had developed a rumble, kind of a ghost-noted technique on the bass that became signature to that live sound. To find somebody that could replace me and dance would have been some work for him, so I think that it was easier for him to try to just persuade me to stay. I was with him all the way to the end of Parade [1986] and that was it. He came back again about six months later and was like, “dude, I want you to be in New Power Generation,” but it was time for me to find my own path. The carrot being dangled ain’t fulfilling me!

AF: “Kiss” has always been one of my favorite Prince songs. Now I know that you had a lot to do with the finished product that you received no credit for.

BM: That song was for Mazarati. Now Prince did it better. I mean, he killed it! But it wasn’t for him. It was created for a funk-rock band. But he heard that groove and he said, “We need to keep this for ourselves.” And I was like “oh, we huh?” He was dangling that carrot in front of me again and I trusted him. I cringe when I hear that on the radio because I never got paid. I shoulda retired on that song and I never got a penny.

AF: You discuss in the book some of your encounters with racism. What was your response to the string of recent highly publicized incidents of police brutality against Black Americans, including the death of George Floyd in your hometown of Minneapolis?

BM: It disgusts me, but it does not surprise me at all. Up north, racism is hidden, very systemic. People don’t know they’re racist, and that’s when it gets really bad. They’ll stab you in the back in two seconds. That’s what I grew up with in Minnesota.

What happened to George Floyd did not shock me at all. Under this new administration, racism has reared its ugly head. But I’m kinda glad, because it’s like a boil coming to a head. I’ve always said that unless white America grabs a hold of this issue, it ain’t ever gonna get solved. Now for the first time in my life, I am seeing white America stand up and saying enough’s enough. The difference between when I grew up and now is that we’ve got cell phone cameras. The video has been the most powerful testimony to what we’ve been screaming about for decades. I’m tired of people saying that we always play the race card. I’m an educated Black man who’s gotten his butt kicked by the cops on more than one occasion. It’s real. It’s not about a race card.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

I had no idea who BrownMark was and kinda had a small idea who Prince was. I like the MUSIC, never cared WHO the artists were. I first heard Brown Mark doing “I Just Wanna Be” a song I LOVED and had when it first came out. STILL have it on casette. BrownMark has this innocence about him, you can see it in his eyes and love of his music. Pure joy shines from his face.

Since finding out more about him and Prince, well, it was really rotten of Prince to take his song. BrownMark, now that I have seen a few of his videos and his playing, is a fantastic bass player.