Book Review: Crime and Espionage — to the Sounds of Jazz

By Steve Provizer

There’s a larger story to tell about Black composers and musicians breaking into the film and TV business, but it’s only lightly touched on here.

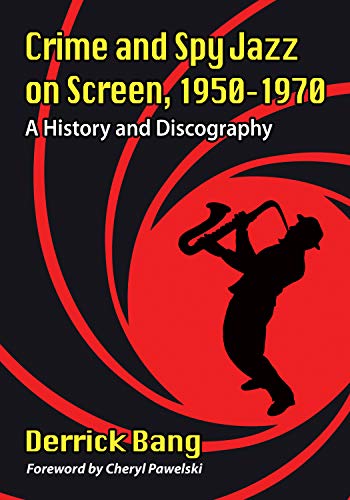

Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen, 1950–1970: A History and Discography by Derrick Bang. McFarland & Company, 312 pages, $54.

Click here to buy

At 312 pages, 250,000 words, and 550 film and television shows, it’s hard to imagine anyone sitting down and reading this book from cover to cover. Just poking through the index would be a half-day affair. But if you need to know who wrote the theme song of Patrick McGoohan’s series The Prisoner (Ron Grainer), who scored the film The Manchurian Candidate (David Amram), or who played on the theme song of M Squad (Count Basie) this is the tome for you.

Most film books either feature extended reviews of selected films or they are compendia (like David Meeker’s Jazz in the Movies) that provide brief encapsulations of films that fall into the genre under investigation. In Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen, Derrick Bang makes use of a hybrid approach. He serves up plot summaries, identifies who got the soundtrack gig, and dispenses highlights of how the music is used in the film.

Here’s a typically pithy and workman-like entry on the 1968 show The Outsider: “McGavin’s Ross is a world-weary underdog without friends or family, who nonetheless possesses moral certainty and a strong sense of justice. He’s a proto-Jim Rockford — both came from creator Roy Huggins — down to idiosyncratic quirks such as Ross’ habit of keeping his telephone in the refrigerator. McGavin fits the role perfectly, his morose demeanor emblematic of a guy forever trying to retain a little dignity…Pete Rugolo’s title theme is a midtempo jazz ballad with a somber guitar melody against occasional flashes of brass; it plays over a montage of Ross enduring a breakfast of burnt toast and sour milk. Reeds and strings add a brief countermelody before a concluding brass fanfare. The show’s underscores are unremarkable, likely built from library cues. Rugolo never recorded the theme; it’s as lost today as the series itself.“

Certain names appear frequently: Henry Mancini, Jerry Goldsmith, Lalo Schriffrin, Johnny Williams (jazz pianist, later Mr. Star Wars), Franz Waxman, Elmer Bernstein, Pete Rugolo, Quincy Jones, Don Costa, Shorty Rogers, Oliver Nelson, and John Lewis. A few scattered efforts by Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, Don Ellis, and some others are also covered. Bang writes about jazz soundtrack developments in other parts of the world, chiefly in France and England, where John Dankworth and John Barry receive a lot of notice. Barry, in fact, probably garners more space than any other composer in the book. If the name doesn’t ring a bell, he’s the brains behind the James Bond music. Granularity example: “For Dr. No, Vic Flick used a “big, blond, f-hole Clifford Essex Paragon cello-bodied guitar, fitted with a DeAmond Volume Pedal into a Vox 15-watt amplifier.”

I’ve always been fascinated by how jazz has been encoded in films. During the noir era — call it post-World War II to the mid-’50s — jazz was often used to signal the potential arrival of mayhem and sexuality (by way of “diegetic” music, live musicians performing on screen, tunes heard on jukeboxes, record players the characters can listen to). Ironically, the music itself was rarely heard on the soundtracks, which mostly used the hallowed bag of tricks developed by the likes of Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, and Adolf Deutsch.

Bang himself doesn’t directly address the “moral” aspects of how jazz is used in film. He clearly has an unresolved attitude toward associating jazz with crime and sex — “the sordid.” On one hand, he writes: “Scripter Abby Mann’s adaptation of Roderick Thorp’s 1966 novel, The Detective, is appallingly homophobic and sensationalistic; while the adult content may have been viewed as ‘progressive’ in the late 1960s — lurid sex crimes, nymphomania — it has since become exploitative and wincingly offensive.” On the other hand, he uses phrases like “voluptuously carnal” and “Johnny Hodges’ salacious alto sax.” I don’t think his tongue is in his cheek when he opines about the 1956 film Baby Doll, “No wonder church going folks still regarded jazz as ‘the devil’s music.’” But, to be fair, this kind of analysis is beside the point given Bang’s framework, which is to accept the small-bang-thank-you-ma’am ethic of the films he’s reviewing and cut to the chase.

In the early ’50s, some jazz finally began to be heard on screen. One of Bang’s more interesting stories deals with how Marlon Brando made sure that music by Shorty Rogers would be used in The Wild One (1953). Rogers believes that, because of this opportunity, Hollywood opened up for jazz musicians: “anyone who could play bop began to get calls to play for films.”

Elmer Bernstein pulling out all the jazz stops for the score of 1955’s Man with the Golden Arm was hugely influential. Following up on this achievement, Mancini’s theme and music for Peter Gunn (he did 114 scores for the show) sold more than 1 million copies. Unsurprisingly, this success inspired the scores for detective and cop shows such as The Lineup, Richard Diamond, Thin Man, and M Squad.

There is a larger story to tell about Black composers and musicians breaking into the film and TV business, but Bang only lightly touches on that. Count Basie’s was the first Black band to do a TV theme. Years later, Mancini had to vouch for Quincy Jones’s ability to a skeptical producer who thought Black composers “couldn’t write for strings.”

Joseph Mullendore scored TV’s Honey West. Do you need to know more?

The book would be improved if the author let the composers speak more for themselves. There are only nine original interviews listed by Bang and the talks tend to be along the lines of Mort Stevens on the Hawaii-5-O theme: “It took 11 minutes to get the basics down,” Stevens recalled. “The simplicity of it, and the driving force of instruments rather than simply the drums, made it into a popular rhythmic entity. With two trumpets playing the melody, and two trumpets playing the same melody an octave lower, it sounded like a blunderbuss coming at you.” OK, but far from zingy.

There’s much to learn here. It’s cool to know which shows on a series might have something to do with jazz, for instance,“Memos from Purgatory” and “Crimson Witness” in Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Bang covers the long history of soundtrack albums made or singles developed and recorded for hit shows extensively. There’s a very useful discography, often listing the musicians on the session. The bibliography is solid and, as I said, the notes and index are good resources. But for any writer interested in following up on this subject — good luck. Bang is nothing if not a completist. I suppose there’s more to learn about Joseph Mullendore than the fact that he scored Burke’s Law and then Honey West, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen, Derrick Bang, McFarland & Company

Steve … thanks for the thoughtful review; I’m grateful. I don’t believe I’ve been called “pithy” before; that’s a great adjective. And, honestly, I’d love to have included a lot more composer quotes — I certainly had more — but McFarland was adamant about word count. One minor thing: The stats you quote at the top — 250,000 words, 550 films/TV shows — refer to the combined total in both books, although you’ve just discussed Volume One here. I don’t want fans to miss the second (and sadder) half of the saga!

Derrick-Thanks for the correction and clarifications.