Opera Album Review: Who Knew? Brazil’s Finest Opera is in Italian

By Ralph P. Locke

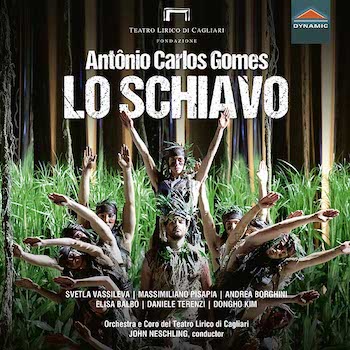

Antônio Carlos Gomes’s Lo schiavo (The Slave) receives its first major recording — and stakes its claim in the repertory.

Antônio Carlos Gomes, Lo schiavo

Svetla Vassileva (Ilàra), Elisa Balbo (Countess di Boissy), Massimiliano Pisapi (Américo), Andrea Borghini (Iberè), Daniele Terenzi (Gianfèra), Dongho Kim (Count Rodrigo, Goitacà) Cagliari Teatro Lirico/ John Neschling

Dynamic [2 CDs] 132 minutes

To purchase, click here.

Antônio Carlos Gomes (1836-96) was Brazil’s most successful opera composer, yet, because he spent most of his professional life in Italy, his operas are almost all in Italian. A new recording — the first major one — of his Lo schiavo (The Slave) proves why he was so widely appreciated in Italy and Brazil in the late nineteenth century and brings us a work that can hold its head high along with repertory staples such as Ponchielli’s La gioconda. I suspect we have now found Gomes’s best opera, which therefore is also, most likely, Brazil’s best.

Antônio Carlos Gomes (1836-96) was Brazil’s most successful opera composer, yet, because he spent most of his professional life in Italy, his operas are almost all in Italian. A new recording — the first major one — of his Lo schiavo (The Slave) proves why he was so widely appreciated in Italy and Brazil in the late nineteenth century and brings us a work that can hold its head high along with repertory staples such as Ponchielli’s La gioconda. I suspect we have now found Gomes’s best opera, which therefore is also, most likely, Brazil’s best.

Twenty years ago, in American Record Guide, the indefatigable Charles H. Parsons reviewed recordings of seven operas or other stage works, plus an oratorio, by Gomes. The recordings came from a variety of sources, and their release was sponsored by the Ministry of Culture of the Governor of the State of São Paulo. The sound was mostly execrable (e.g., recorded from a seat in the auditorium); the performances were often rough-and-ready, though spirited. Parsons was able, in passing, to mention that one of the operas, Il Guarany (1870), could also be heard in a somewhat bland but much more accomplished performance (Sony, 1992, recorded in Bonn) starring Verónica Villarroel, Plácido Domingo, Carlos Álvarez, and Hao Jiang Tian. He concluded: “Such is the excellence of much of Gomes’s music and drama that his entire oeuvre needs to be re-examined and published in decent modern editions and recordings.”

You may in fact know one number by Gomes: his “Mia piccirella,” a kind of Neapolitan song, has been a hit for over a century, with recordings by Caruso, Claudia Muzio, Roberto Alagna, and others. It comes from Gomes’s opera Salvator Rosa (1874).

Well, Mr. Parsons (who passed away in 2018) would have been pleased to hear that Lo schiavo can now be had in a persuasive (and not bland) modern recording. Hearing it confirms the favorable view of the composer expressed by Verdi authority Julian Budden, who discussed Gomes as one of “the three outstanding figures” in Italian operatic composition during the years 1870-90 (alongside Catalani and Ponchielli). Budden went on to describe Lo schiavo and his other operas in appreciative detail (The Operas of Verdi, vol. 3, pp. 281-91).

Gomes was born in Brazil to a family that stemmed mainly from the Iberian Peninsula, but one grandmother was a native of the indigenous people known as the Guaraní. Early on, Gomes composed two operas in Portuguese that got performed in Rio de Janeiro. He was then sent to Italy for further musical training and ended up staying there for most of his life, writing six full-scale operas as well as three operettas and incidental music for a play. All those works were in Italian, and all but one of them were staged in Italy, sometimes receiving subsequent productions in several other Italian cities than the one where the work had its premiere.

Lo schiavo (1889) is Gomes’s only mature opera to have been first performed outside Italy, namely in Rio de Janeiro. He took on the project at the suggestion of the Brazilian Viscount Taunay, an ardent opponent of slavery. Taunay drafted the scenario, and another writer (Paravicini) expanded it into a full Italian libretto. Budden describes the first production as an “unqualified triumph.” The plot involves tensions between and within two groups: colonists and slaves. The viscount had set the plot in 1801 and made the slaves African in origin (reflecting the massive numbers of enslaved Africans that had been brought over to Brazil during the preceding two centuries). The completed libretto, though, moved the action further back in time (to 1567) and made the slaves indigenous Brazilians, that is, what were often called “Indians” or, simply, “natives.” Perhaps the opera’s creative team feared that using very dark makeup would be thought tasteless, evoking such things as blackface minstrel shows.

I saw a production of Gomes’s Il Guarany (his best-known work) at the National Opera in Washington, DC, decades ago. Domingo was in the title role as a native Brazilian warrior, with memorably large feathers sticking up from his head. Lo schiavo shares many of its basic features: vigorous and tuneful solo and choral writing, highly melodramatic situations, bold and varied orchestration that comments powerfully on the characters’ actions, and a naive (or, depending on your point of view, infuriating) representation of the relations between the native population of Brazil and their European conquerors.

Most importantly, Lo schiavo comes across as a very effective work, stageworthy and musically gratifying. The Act 1 prelude is particularly beautiful, beginning with a modal oboe solo and some shimmering string passages that seem to evoke the “primitive” native tribe and their once-peaceful forest homeland. This orchestral number could easily become a pops-concert favorite. The prelude to the final scene is even longer and no less atmospheric. Several solos for the main soprano, the tenor, and the baritone could likewise be excerpted for use in concerts or recitals. Indeed, one of them — the tenor’s “Quando nascesti tu” — was recorded by Enrico Caruso and by Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, though the opera itself never reached Italy. (The Cagliari production heard here was, astoundingly, the work’s Italian premiere!)

Svetla Vassileva as Ilàra, an Indian girl, in Lo Schiavo Teatro lirico d Cagliari. Photo: Priamo Tolu

There are also broad, stirring tunes in several ensembles, much as in the so-called sextet from Lucia di Lammermoor or in some of Verdi’s middle-period operas. A scene in which the natives vow to attack the slave-owners is very effective, recalling other scenes, such as in Norma or Simon Boccanegra, in which a people cries out in opposition to tyranny. You can taste a few of the tracks at HBDirect or watch this trailer on YouTube. The complete recording can be heard on various streaming sites.

The plot incorporates many elements that were typical in Italian operas of the era. I suspect that Aida (1871) was particularly on the makers’ minds: after all, it was the best-known Italian opera to focus on tensions between a powerful light-skinned people and an oppressed darker-skinned one. The Aida figure here is the native woman Ilàra. She loves, and is loved by, the Portuguese man Américo, whose father owns the plantation and is opposed to the relationship between the two. (He is thus the Radamès figure. Another parallel: he is captain in the army fighting to put down a revolt by the native people.) Countess Boissy is a high-class lady who (much like Amneris in Aida) wants the heroic captain (Américo) for herself.

There are differences as well. Quite unlike Amneris, the Countess argues for the abolition of slavery and even frees some of her slaves on-stage. Ilàra is pulled away from Américo, not by a father (Amonasro in Aida), but by a fellow slave, Iberè (baritone), who is devoted to her (though she of course loves the tenor). Américo saves the lives of Iberè and Ilàra in Act 1, and Iberè therefore feels he cannot in good conscience take up arms against the man and his troops. At the end of the opera, Iberè allows the loving couple to flee. The native troops threaten to kill him for betraying their cause, but, highly principled figure that he is, he stabs himself before they can. Good operatic fun, I’d say! (One clue to following the plot: Iberè is the guy who is not from the Iberian peninsula, and Américo is the one who is not a native of the Americas. I suppose Américo’s name alludes to the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, but it’s still confusing.)

The singers here are an international lot, but they all know what to do in Italian opera of the Verdi-to-verismo era. Bulgarian soprano Svetla Vassileva has a big voice with a nice cutting edge to it that would help it carry in a big opera house. She seems to be a very dramatic actress (to judge by photos in the booklet). Her voice also has a near constant slow throb (she was 53 when the recording was made), but the music is so straightforward in its harmony that I never had trouble figuring out what pitch she was aiming for. Soprano Elisa Balbo is much younger but, at least on this occasion, has some patches of slow vibrato as well. (I did not notice this in her singing of Anna Erissa in a recent recording of Rossini’s Maometto secondo.) Balbo handles ably the patches of coloratura that Gomes gives her (to emphasize her high social class and also her sometimes-bantering manner). Massimiliano Pisapia and baritone Andrea Borghini are first-rate as the two men who love, each in his own way, the slave woman. Korean bass Dongho Kim excels in two roles requiring the voice of authority and power: the plantation owner and (his nemesis) the leader of the slave rebellion.

The orchestra of the Cagliari theater plays beautifully, forcefully, atmospherically—whatever is needed. Gosh, regional orchestras are getting good! (Cagliari is the capital of Sardinia.) The style-aware conductor is John Neschling, who was born in Brazil and who has had a major conducting career in São Paulo but also Lisbon and Vienna. He conducted the aforementioned Guarany recording.

The recording comes from a blend of performances in February and March 2019. Vivid photos in the booklet show that the staging was straightforward and sensible — not relocated to Mars or a Nazi prison camp. Bravo for that!

Sonics are excellent. Some applause at appropriate moments. Essay and libretto in Italian and English. The libretto can also be downloaded at dynamic.it (for those who are, say, listening on Spotify). If you like middle Verdi, or Catalani’s delicious La Wally, I urge you to try some Gomes on for size. And the Cagliari festival’s Lo schiavo is perhaps the best place to start.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Cagliari Teatro Lirico, Carlos Gomes, Dynamic, John Neschling, Lo Schiavo, Ralph P. Locke

[…] Antônio Carlos Gomes’s Lo schiavo (The Slave; 1889) may be the best opera by a Brazilian composer, even more effective than his Il guarany, which Plácido Domingo revived and recorded in the 1990s. Composed, like most of Gomes’s works, in Italian, it is heard in an energetic yet generally well-controlled performance by an international cast under Gomes authority John Neschling (who also led the Il guarany recording). […]