Book Review: A Treasury of Tall Tales That Make Opera Fun

By Ralph P. Locke

Author Ethan Mordden serves up plenty of entertaining yarns, sometimes as exaggerated as the genre to which they pay homage.

The New Book of Opera Anecdotes by Ethan Mordden. Oxford University Press, 328 pp., $19.95 (“a paperback original”).

Click here to buy.

I have friends who tell me, “I don’t get opera,” or “You couldn’t pay me to sit through one of those.” Some of them are big classical-music fans: people who are nuts for Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, Schubert’s Winterreise, the Brahms Piano Quintet, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Yet they don’t connect to what’s on stage in most operas. Or they can’t stand a singer’s sometimes-wobbly long notes.

I have friends who tell me, “I don’t get opera,” or “You couldn’t pay me to sit through one of those.” Some of them are big classical-music fans: people who are nuts for Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, Schubert’s Winterreise, the Brahms Piano Quintet, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Yet they don’t connect to what’s on stage in most operas. Or they can’t stand a singer’s sometimes-wobbly long notes.

I understand their reluctance. After all, I have no desire to eat brain or tripe — each of which I tried once. We all are entitled to our preferences. (Except as regards, say, getting one’s children vaccinated, wearing a seatbelt, or — during an epidemic — wearing a mask and maintaining a six-foot distance.)

I love this gangly, extravagant genre: listen intently to recordings, seek out performances by regional opera companies and university opera workshops, and attend most of the Met’s HD transmissions in our local movie theater and watch the rest when PBS broadcasts them some months later (or, currently, I stream them). So, when people ask me how to get “into” opera, I have a ready supply of great suggestions, including some recordings and books. I’ll mention those at the end.

But now I have a new book I will heartily recommend to them: Ethan Mordden’s The New Book of Opera Anecdotes. I don’t know his 1991 Opera Anecdotes (to which this book is a sequel), but it clearly sold well: there are 491 copies listed in WorldCat alone (an incomplete but amazing catalog of the world’s libraries). Copy no. 488 belongs to the Environmental Protection Agency in Australia’s Queensland. Apparently you need to have a ready stock of anecdotes about Maria Callas if you want to fight wildfires or save a coral reef!

Oxford University Press must have been delighted that Mordden, a New York-based writer best known for his many well received books about the history of the Broadway musical, was willing to put together a second book of witticisms and tall tales about opera. There are endlessly many such “anecdotes” (to use Mordden’s preferred term). Indeed, sometimes it seems to me that opera is a bit like football and other spectator sports: people get as much fun talking about it as actually experiencing the thing itself.

I was prepared to hate Mordden’s book, in part because the author admits at the outset that he has here retold “in my own voice” stories that he has read or heard. But I ended up loving it — could hardly stop reading. Now that Mordden has entertained me for some 300 pages, I would be a churl, indeed, to complain.

Many of the stories here are about recent or currently active singers, such as Renée Fleming and Jonas Kaufmann. But some are about major performers from the past, such as Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, whose increasingly half-spoken (or -shouted) performances as Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio were sharply criticized by Berlioz.

The stories (jokes, etc.) are often drawn from memoirs and other published sources, but some come from that elusive category: word of mouth. Mordden repeatedly warns us that certain stories were probably already somewhat embellished even in their earliest appearances in print, and that others barely pretend to be factual. He prefaces one with the warning: “In another of those beloved bits of lore kept alive over the years by Met standees….” (“Standees” are the students and other opera lovers of modest means who pay a small fee to stand at the back of the hall for the entire performance, usually leaning their arms on a high railing and sometimes keeping up a quiet commentary with each other.) The book contains no footnotes or bibliography to help a reader locate the longer passage from which a story has been drawn (and often, here, reworded). But Mordden does allude to some of his sources in passing: standard biographies of, say, Richard Strauss, and memoirs by such active shapers of operatic life as Joseph Volpe, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera before the current reign of Peter Gelb.

Luciano Pavarotti performing in 2003. Photo: Wiki Commons.

The highly varied source material, plus Mordden’s own playful elaborations and word-colorings, results in a collection of vignettes and tall tales that alternate, and sometimes mix, factual information with recollections, personal impressions, and fantastical inventions — all of which possess their own kinds of truth. Not least, the various entries reflect a shared passion for this wild and woolly (and, yes, highly theatrical) genre and the many-headed industry that surrounds and enables it. They also give evidence for what various writers and dinner-party raconteurs have tended to think would hold the attention of their readers or listeners.

My favorite story in Mordden’s New Book touches on a revealing fact about Luciano Pavarotti: he was never much comfortable reading musical notation and was unusually dependent on others to help him commit his roles to memory. (Conductor Richard Bonynge said as much in his memoirs.) The story that Mordden tells to illustrate this point involves a production in Rome of Verdi’s early-ish opera I Lombardi. Pavarotti had never sung the role of Oronte before. At the first rehearsal, it became apparent that the tenor had learned Oronte’s words and vocal line only through the end of Act 3, where the character dies. The conductor — the renowned Gianandrea Gavazzeni — pointed out to the great tenor that, in Act 4, Oronte’s voice is heard, in a kind of apotheosis, as an offstage voice from on high. Mordden’s version has Pavarotti “snapping his score shut” and leaving the room, so someone could teach him the rest of the role. The most fun part is Pavarotti’s farewell shifting of the blame: “If Verdi wanted me to sing in Act Four, he shouldn’t have killed me off in Act Three.”

Did Pavarotti actually say that? Did he later wish he had said it? Or were the words put in his mouth by some wag? Maybe it doesn’t matter. Similarly, Mordden’s wording “Pavarotti couldn’t read music” is presumably too categorical; after all, the singer, when young, took voice lessons for seven years. Presumably his teacher taught him at least some rudiments of note-reading. But we get the point, and to object to every exaggerated statement in the book is to wish for it to be a different book — and a less amusing one.

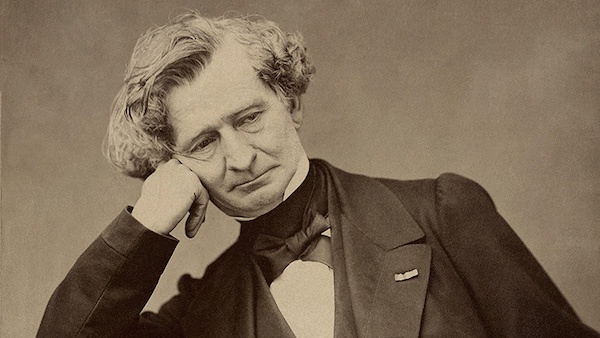

Photo of composer and critic Hector Berlioz by Pierre Petit (1863).

One of the book’s greatest strengths is its decision to focus for pages at a time on a small number of crucial figures. These include singers such as Callas (of course), Kathleen Battle, and, earlier in the twentieth century, Caruso; imperious conductors such as Toscanini and Karajan; and five composers: Verdi, Wagner, Puccini, Richard Strauss, and — a surprising but refreshing choice — Berlioz, whose largely forgotten Les Troyens became one of the great musical rediscoveries of the late twentieth century.

Equally welcome is Mordden’s puckish authorial voice. A published short-story writer, he reveals his enjoyment of language on every page. Joan Sutherland, he reports, was unique: a “bel canto coloratura with a gigantic voice and, under the right director, even a magnetic presence created out of a complete inability to act. One was mesmerized waiting to see what she wouldn’t do next.”

One “sweetly comic role,” though (Marie, in Donizetti’s The Daughter of the Regiment), “brought out the Dickens in the diva.”

As regards the famous opening night of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, which was obstructed by audience members who apparently had been paid by a rival of Puccini’s publisher:

The organizers of the demonstration guided the entire audience—some two thousand people—in just when to harass the performance and when to remain angrily silent, in effect drawing even those who were neutral into taking part while intimidating would-be Puccini partisans.

Each story is given a humorous or pointed title, such as “Blame of Thrones” (for the occasion when the audience at La Scala booed Roberto Alagna in Aida). Or “Crime of Fashion.” The latter heads an anecdote by Berlioz about a too-jangly piano in a performance in Berlin of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Mordden misreports (perhaps because he was relying on a bad old translation) that Berlioz said that a clavichord was used. This is of course impossible: the clavichord is a famously quiet instrument, never used in big halls. Berlioz actually wrote that the piano in question was as tinny-sounding as a clavecin, a French word that means harpsichord. He didn’t write clavicorde. Berlioz’s point was that the instrument was a piano with a peculiarly edgy tone. (I suspect it was chosen to help keep the large chorus in tune with the orchestra.) In any case, the result was clearly offensive to Berlioz’s ear, ever sensitive to instrumental color.

Note: Mordden’s book, of course, doesn’t remotely replace more serious ones about opera. Here is a short list of some of my favorites:

The Grove Book of Operas, ed. Stanley Sadie and Laura Macy. (If you only buy one book on opera, this is the one I’d recommend: background, plot summary, and musical discussion for over 200 wondrous works.)

Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker, A History of Opera, updated edition (paperback).

The Oxford Handbook to Opera (ed. Helen M. Greenwald).

Joseph Kerman, Opera as Drama.

Julian Budden, The Operas of Verdi, 3 vols.

Ernest Newman, The Wagner Operas.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, Wexford (Ireland), Bilbao (Spain), and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).