Book Review: “Urban Legends: The South Bronx in Representation and Ruin” — Naked City

By Mark Favermann

Peter L’Official has written an important book that speaks with powerful relevance to the state of Black life in America today — and the demands of Black Lives Matter.

Urban Legends: The South Bronx in Representation and Ruin by Peter L’Official. Harvard University Press, 320 pages, $29.

Initially, I didn’t want to read this book. Given my current predicament, a seemingly perpetual COVID-19 despair, it just didn’t appeal. Why look in-depth at such a past imperfect time and place — ’70s South Bronx? But curiosity got the best of me and that was fortunate: I happily devoured Peter L’Official’s terrific cultural narrative, which explores the creative renaissance of an inner city NYC borough, once a poster child for social turmoil, economic wreckage, and physical devastation.

Born and bred in the Bronx, this talented scholar/author (an assistant professor of literature at Bard College) deftly and vividly examines the realities and myths of the Bronx’s extremes: civic neglect, crime, and urban decay, even ruin, versus cultural innovation and an outstanding artistic legacy.

Through the ’60s and 70s, the South Bronx epitomized America’s nightmare visions of the inner city. The Bronx was the most prominent image of “the ghetto” for the nation: desolate urban neighborhoods populated by poor communities of color. Gritty images of deteriorating edifices were shown on TV news stories as well as in newspapers and magazines. Some of the most searing (literally) visuals were broadcast live during the 1977 World Series: pictures and films of a squalid building on fire near Yankee Stadium.

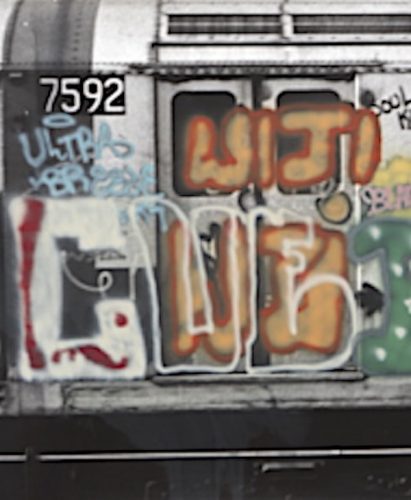

Urban Legends presents a new cultural history of what it meant to live, work, and create in the Bronx. It was far from the stereotypical and racist view of the area as a lifeless morass, Arguably, the Bronx gave birth to one of the most powerful revolutions in music of the past 50 years — hip-hop was born and matured in the Bronx. And there’s more: though the form dates back to the cave paintings, a contemporary form of graffiti evolved out of the South Bronx. Eventually, graffiti inspired by these New York artists was exhibited internationally in galleries and museums.

Grafitti on MTA Subway car, 1971 by Gordon Matta-Clark. 1973 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Drawing on literature and the visual arts, and discarding falsehood and legends, L’Official looks at the history, people, and geography of the Bronx. Despite popular, often distorted, caricaturizations, the Bronx was not a decades-long roaring funeral pyre; nor was hip-hop its only major cultural contribution. The author eloquently disputes the misjudgments of lax journalists, refutes exaggerated assumptions, and disqualifies misplaced political rhetoric. He uses the words, images, and voices of contemporary writers, visual artists, entertainers, and social scientists, along with residents and business owners, to paint a nuanced portrait of the South Bronx.

DJ Kool Herc, aka Clive Campbell, a Jamaican immigrant and Bronx resident, is considered the father of hip-hop. In 1973, he reportedly hosted a party in his building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue with sound equipment a DJ used at a party. The sound system included a guitar amp and two turntables. DJ Kool Herc’s playful manipulation of sound and technology launched a form of popular entertainment that has permeated mainstream culture around the world.

Street art and graffiti came out of the rise of hip-hop and gang culture in the Bronx during the late ’70s. Lee Quiñones and Fab 5 Freddy were two of the area’s earliest street artists. Initially, their drawings on the sides of subway trains were seen as nuisances, ven crimes. But over the years their artwork — and then their followers’ creations — were accepted as collectable gallery art.

South Bronx, 1980. “Falsas Promesas Broken Promises.” Photo:John Fekner, Wiki Commons.

Two major authors that are referenced in the book include Don DeLillo, known for his novels White Noise and Underground, and the late Tom Wolfe, particularly The Bonfire of the Vanities. Both of these celebrated American writers were steeped in the South Bronx: this sense of connection informed their writing, driving their similar notions of life as a turbulent life journey, a struggle to move from the low to the high.

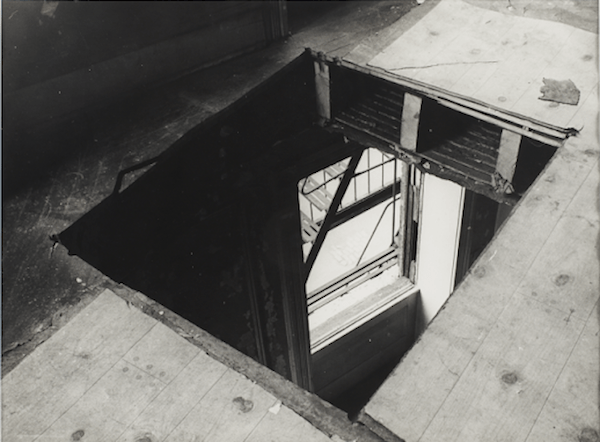

One of the most influential visual artists inspired by the Bronx was the short-lived Gordon Matta Clark (1943-1978), who specialized in visually documenting social devastation, focusing on the traumatic optics generated by physical decay. Today, the concept of social justice is part and parcel of the work of many artists. Matta-Clark pioneered a socially engaged approach to creativity 50 years ago, concentrating on issues of inequality, political insensitivity, public works expediency, and overt as well as covert racism. As much urban archaeologist as he was a visual artist, he reconceptualized roles and relationships between people and spaces and between people and formal architecture. The author effectively makes his point by comparing the superficiality of the City of New York’s trompe l’oeil decals program (images of windows, doors, etc.) to the visual authenticity of Matta-Clark’s artwork.

Gordon Matta-Clark, “Infinite Light,”1972 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Even more powerfully, L’Official considers the often pejorative terms of “inner city,” “blight,” “ghetto,” and other metaphorical constructs of place that have been — and still are — used to unfairly characterize cities, neighborhoods, and the people who live in them. Rightly, he sees how these words are used as demeaning euphemisms, shorthand descriptions for complex problems that are generated by oppressive entrenched systems, political and social power dynamics, and institutional constraints. Language is used as a form of self-protective distancing, coded terms for Black and Brown residents whose crudeness aids and abets a lack of comprehension and progress.

Urban Legends is constructed of parallel and intertwined narratives. These include investigations of symbols, images, and systems, of how they interact, compete with, and often contradict each other. There is a focus on artists, writers, and social thinkers, as well as an examination of the processes and civic systems that contributed to the breakdown and eventual decay of the Bronx and other large urban areas. The visual stigmatization of the South Bronx was a political/economic strategy, born of bureaucratic and institutional incompetence as well as a dearth of political will. These and other failures were blamed on the people who populated the borough and its neighborhoods. L’Official has written an important book that speaks with powerful relevance to the state of Black life in America today — and the demands of Black Lives Matter.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Harvard University Press, Mark Favermann, Peter L’Official