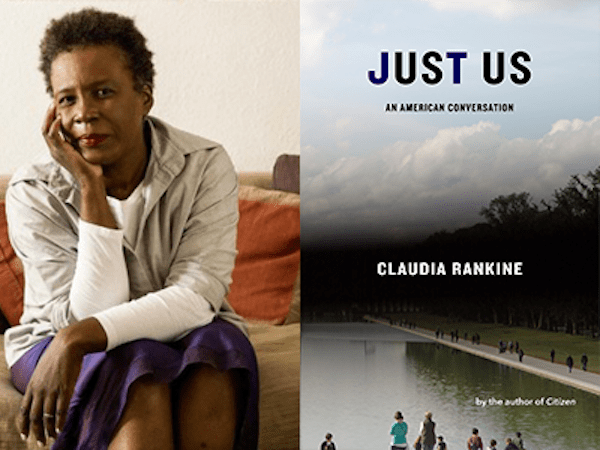

Book Review: Claudia Rankine’s “Just Us: An American Conversation” — Tough Talk about Race

By Ed Meek

Claudia Rankine comes off like a disgruntled but interesting guest at a dinner party who keeps turning the conversation back to subjects that make others uncomfortable but are well worth talking about and seriously examining.

Just Us: An American Conversation by Claudia Rankine. Graywolf Press, 338 pages, $30.

A hybrid work of nonfiction, Just Us: An American Conversation is a patchwork quilt of thoughts, musings, conversations, charts, images, facts, and quotes. Rankine, a poet and Yale professor, draws on her perspective and experience as a citizen and successful Black intellectual to articulate her thoughts about racism and whiteness in the United States. Perhaps partly because she has become such a publicly recognized Black thinker (for her poetry collections, such as Citizen: An American Lyric, and play The White Card), she is obsessed with racism and America’s inability to come to terms with it. As she puts it, “Black personal achievement does not negate the continued assault of white terrorism.” If you have read (or read about) How to Be an Antiracist and White Fragility and you want a more personal perspective on the subject of racism, Just Us provides just that.

Rankine thinks associatively rather than sequentially, so the book is episodic rather than arranged as an argument or a narrative with a narrative arc like, say, Ibram Kendi’s polemic. Kendi also fashions a charming persona on the page. Rankine is more like a disgruntled but interesting guest at a dinner party who keeps turning the conversation back to subjects that make others uncomfortable but are well worth talking about and seriously examining

She tells a number of stories about micro-aggressions by whites that happen to her and other Black women. She is waiting in line for a first-class seat at an airport when a white woman cuts in front of her. She asks the woman whether she noticed that she was standing in line. The woman claims she made a mistake, but did she really? Later, in another line at the airport, a group of white men form their own parallel line to get on a plane. They treat their strategy as a joke. Rankine’s point is, these things happen to Black Americans all the time. She tells us about a conversation with a white male sitting beside her on the plane who characterizes himself as “colorblind.” This is one of the lines of attack in White Fragility. Whites seem to think we live in an egalitarian society where all lives matter and everyone has an equal chance to succeed. Rankine retorts: Does he not see me as Black? When she tells him she teaches at Yale, her seatmate mentions that his son hadn’t been accepted into Yale but might have if he’d been a minority. Rankine points out the white resentment of Brett Kavanaugh, who whined about how he “worked his butt off” to get into Yale without anyone’s help. Though his grandfather went there.

Rankine ties these experiences into white privilege, but she prefers the term “white living” because not all whites are economically privileged. Nonetheless, when it comes to wealth, whites are much better off than Blacks. Whites without high school degrees have more wealth than Blacks with college degrees. Blacks in the top 10 percent of income earners have about 20 percent of the wealth of whites. What may be surprising is that the wealth gap between Blacks and whites has grown worse over the last 20 years. This is partly because Blacks were hurt more than whites by the Great Recession — many never recovered from it. On the whole, as Rankine reminds us, whites have 10 times the wealth of Blacks in the United States.

Rankine also analyzes some of the unconscious ways we value whiteness, from skin color to blond hair. She struggles with why this is true among people of color as well as whites. It should be noted here that she calls the book “a conversation,” and you may find yourself arguing with her. Aren’t there many beautiful Black celebrities, from Beyoncé to Lupita Nyong’o? She considers hair-straightening and Black women who bleach their hair blond and wonders what that might mean. She doesn’t always have answers to these questions. She also takes up issues that touch on the Latin community, speculating about divisions between Latins who consider themselves white and those who consider themselves persons of color or Black.

She points out that Americans gave themselves credit for electing Barack Obama, a Black president, but exit polls from 2008, 2012, and 2016 show that a majority of whites consistently voted Republican. It was Blacks and other minorities — voting en masse for Obama — that enabled him to be elected.

Rankin wonders “What will it take for white Americans to change?” Following the death of George Floyd, masses of Americans have been calling for justice. A shift in our attitudes toward racism seems to be underway. Near the end of the book, Rankine argues that “reparations would mean a revolution of the American Consciousness…the great equalizer.” But, according to the latest polls at 538.com, only 26 percent of Americans support reparations. Yet most Americans support changes to an unjust justice system, such as ending mandatory minimum sentences and enabling former felons to vote. Americans are also in favor of increasing racial diversity on college campuses and bridging racial divides. Most Americans acknowledge that white people have advantages for getting ahead and the country has not done nearly enough to create a fair playing field, social and economic, for Blacks.

At the end of Just Us Rankine tells the story of Ruby Sales, a Black activist. In 1965, a white man, Jonathan Daniel, knocked Sales down and took a shotgun blast meant for her. From this generous act, she concludes that “each of us [is] … capable of both the best and the worst our democracy has to offer.” Rankine begins the book with a poem that she returns to at the end: “what I want / and what I want from you run parallel– / justice and the openings for just us.” Once you’ve read Just Us, order a copy of 2014’s Citizen: An American Lyric.

Ed Meek is the author of Spy Pond and What We Love. A collection of his short stories, Luck, came out in May. WBUR’s Cognoscenti featured his poems during National Poetry Month in 2019.