Life Commentary: A Cultural Journalist Dealing with Cancer During Covid

Editor’s Note: Helen Epstein is a longtime contributor to The Arts Fuse, writing book and theater reviews. Her reflections on her recent health challenges have enormous relevance now, and they also pay homage to the amazing efforts of the medical profession. This piece was originally published in NextTribe, a digital magazine for smart, engaged women over 45 that comes out of Austin, TX. — Bill Marx

By Helen Epstein

It’s never a good time to be diagnosed with cancer, but June 10th, 2020, was among the worst. By that day, 7,454 people had died of COVID-19 in my state of Massachusetts.

A selfie of the author in the hospital.

After our governor declared a state of emergency on March 10th, my husband and I went into lockdown in our Boston suburb. This scuttled all plans for the future. On March 16, I was supposed to have set off on a book tour for my mother’s memoir, Franci’s War, flying to New York, Washington, London, and Prague. But Boston, NYC, and DC shut down, my British editor came down with COVID, and Czech publishing came to a halt.

My life did not change as radically as the lives of others. Patrick and I both continued to work from home and walk our dog. I followed Facebook posts of doctor friends with extra attention, and we listened to Chancellor Angela Merkel, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, and Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Like thousands of others, we canceled routine dental and medical check-ups, including my pelvic ultrasound, scheduled for April 17. I’m 72. OB/GYNs have followed my fibroids with pelvic ultrasounds for over 40 years. With COVID cases rising every day in Massachusetts, it seemed wise to cancel the latest one. Then, I had unexpected bleeding.

The Diagnosis

On May 20, when there were 1,045 new coronavirus cases in Massachusetts, I drove down an uncannily deserted I-95 to have tests. Fear of COVID had solved Boston’s famous traffic issues. The facility at Mass General West was as desolate as a Hopper painting. One entry point; a team of masked interrogators; no significant others allowed inside; Purell for the hands; fresh mask for the face; a demarcated route to the designated department. My test results showed an abnormally thickened endometrial lining and I was scheduled for a biopsy on June 5.

My fear of the endometrial biopsy overshadowed everything else that week. I prepared for it with painkillers and a sedative, and asked my husband to drive me. By then, new COVID cases in Massachusetts had dropped to 494, but traffic was still sparse and the parking lot deserted. The biopsy was excruciating, but I was so relieved it was behind me that I didn’t ruminate about the results.

Instead, as my husband set up a spreadsheet tracking COVID across the world, I followed media coverage of the murders of black men and women by police officers nationwide. My gynecologist, Dr. Uchechi Amy Wosu, is an immigrant of Nigerian parentage; her assistant, whose hand I clutched during the biopsy, from Haiti. I’ve known both women for a while, but June 5 was the first time I connected police violence to them and thought seriously about how often the five African-American kids—now young adults—I watched growing up on my street were routinely stopped. On June 3, we joined hundreds of our neighbors taking a knee for George Floyd on a mile-long section of Massachusetts Avenue that was part of Paul Revere’s midnight ride in 1775.

Then, on June 10 (267 news cases in Massachusetts), Dr. Wosu gave me the diagnosis of endometrial cancer and sent me to a surgeon at Mass General in Boston.

The Context

Getting diagnosed with cancer was a shock, but the twin pandemics (COVID and police violence) provided context. I found I had coping skills. The book I was promoting was my mother’s memoir of surviving racial and political violence, and typhus. By June 12, my priorities were very clear. I was focused on living each day, while maintaining close contact with family members and friends in more stringent lockdowns in Italy, France, Czech Republic, Argentina, Israel, and California. Some 7,538 people in Massachusetts had died of COVID by then and more than 118,000 across the United States.

Cancer has been around since ancient times and is far better understood. Waiting for surgery seemed less stressful to me than the challenges for many people, losing their jobs, homes, savings, and facing unchecked domestic violence and food insecurity. Dozens of my friends have been living with cancer for years and worried far more about COVID contagion. A Manhattan friend with leukemia traverses Central Park for chemo, having to dodge maskless joggers and cyclists. Now I became one of the millions of other people sharing her vulnerability and anger as the Trump administration and its enablers downplayed COVID, touted the benefits of bleach, and mocked the wearing of masks.

On June 12, my husband drove me to downtown Boston for my appointment with the surgeon. COVID was moving west, and there were “only” 392 new cases in Massachusetts that day, but there was still little traffic. People with heart problems, cancer, and other serious conditions had stopped coming to hospitals. At Admissions, there seemed to be more staff than patients.

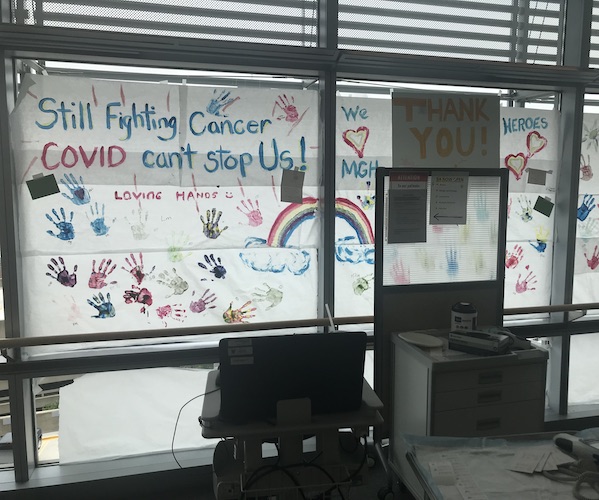

A sign on the oncology floor at MGH. Photo: the author

The Plan

I was the only person in the elevator to the oncology floor at 10:00 a.m. I walked down a corridor that was like an airport terminal at midnight, with a long row of empty seats looking out over a deserted city. Halfway to the waiting room, a woman stopped two feet away from me. Through her mask, she blurted out that in March she had been on the operating table prepped to go, when her cancer surgery was abruptly canceled. COVID, I thought, had worn down even fabled Yankee reticence.

My husband had been told to drive to the top floor of a garage where there was internet access. I texted him photos and updates: a handful of patients in a waiting room meant for 50; the quick check-in and blood draw and chest X-Ray, and EKG. Half the 90 operating rooms were inactive. For the first time, I worried about technicians’ faces close to my own and how many hands affixed tubes and tabs to my skin.

Our conversations were, I thought, more intimate than usual. A white male nurse described his spleen surgery just prior to the lockdown. He and his pregnant wife had deliberately scheduled it before her due date, but the pandemic had complicated plans. His immune system was weakened but he felt safe inside the hospital. Mass General was a kind of oasis where a community of informed, responsible people thrived. But a South Asian technician noted the problem getting to work if you couldn’t walk or commute in your own car. She tried to distance herself from other passengers on public transportation, but someone inevitably sat down right next to her. And the line at Starbucks was dicey, with some customers refusing to wear a mask. Getting a latte had become a risk.

Lying hooked-up to an EKG machine in a hospital, you get how fragile and interconnected the web of daily human interactions is and how a person you don’t know exists can unwittingly threaten your life. Even in educated Lexington, some people walk or run on narrow paths in the woods without masks, and dog-walkers let their dogs off-leash, then run after them and argue when asked to obey the law. After Central Park birdwatcher Chris Cooper video-recorded his incident with a dog-walker, I began bringing my iPhone with me to the woods.

My June 12 meeting with surgeon AK Goodman (white, wearing mask, face-shield, scrubs, and a pair of Texan cowboy boots) recalled unhurried doctor appointments in the pre-HMO 1950s, when physicians searched your face instead of the computer screen. Then, with my husband on speaker phone we discussed the details of surgery, scheduled for June 25. My uterus, fibroids, fallopian tubes, ovaries, cervix and appendix would be removed by a laparoscopic procedure. I would have general anesthesia and a breathing tube. The operation would take three to four hours, with an additional three to four hours recovery time.

The Surgery

Annekathryn Goodman, MD. Gynecologic Oncologist/ Gynecologic Surgeon, co-director of MGH Women’s Global Health. Photo: the author.

I had two weeks to prepare. I organized my house and garden and a group email list. I continued to follow the course of COVID and the protests. I talked to friends, walked my dog, listened to music, and caught up on as many movies and operas as I could (including the movie of Hamilton). I stayed steady until June 23, when the prospect of the compulsory pre-op nasal swab for COVID unnerved me. On June 23, when there were only 229 new cases of COVID in my state, I was so nervous that I asked for a wheelchair to get from the parking lot to the testing tent. Two girlish technicians in PPE suggested I stay in my car instead. I held my husband’s hand. It was unpleasant but quick, and luckily, Dr. Fauci was testifying before Congress and on the car radio.

The surgery on June 25 seemed nothing compared to the news. On that day, the US had set another record for new coronavirus cases, some 40,000. The daily death toll was about 700. CDC Director Robert Redfield estimated that at least 24 million Americans had been infected. Just before midnight, the Department of Justice filed a brief asking the Supreme Court to invalidate the Affordable Care Act, part of a decade-long Republican crusade. The Trump administration was urging states to reopen, people to go back to work, and rejecting the use of masks.

The Aftermath

Waking up in Mass General on June 26, I was grateful to be in a world-class hospital, with a comfortably multicultural staff, in a state whose governor and Congressional delegation defend science. For the next week, I spent hours online. How did people in the pandemic of 1918 manage without it?

By July 10, when we drove back into Boston for a follow-up appointment with my surgeon, new COVID cases in Massachusetts were down to 213, but surges in the South and Southwest had pushed the number of new cases in the United States to 71,000. Florida alone reported 11,433 new cases—making it a new hotspot—but its Republican governor declared he would not slow down Florida’s reopening. Disney World was throwing open the doors to its Magic Kingdom and a maskless President Trump was holding a fundraiser in Miami.

Only patients—still no significant others—were being allowed into Mass General in the fifth month of the pandemic, and there was no one in the elevator with me when I took it up to the still deserted oncology floor. With my husband listening in from the garage roof, the surgeon gave me the results of my procedure. The good news was that I have Stage 1A endometrial cancer, caught very early. The bad news was that I would be returning to Mass General for six cycles of chemotherapy that would take me well past Election Day 2020.

The Priority

I was lucky that my gynecologist insisted that I have a biopsy during the COVID epidemic. I was lucky that the cancer was caught early, that it is well studied. But my well-being—and the well-being of us all—depends not just on luck but on a fragile web of strangers and friends. It depends on responsible political leaders who prioritize the public good over their reelection prospects, and on my journalist colleagues, some of whose work has come to resemble the propaganda of the Soviet era more than investigative reporting. Most of all, it depends on Americans who shrug off inconvenience and observe the social distancing and masking measures that have defeated COVID-19 in other countries.

As I start chemotherapy, I feel a kinship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who has been through this drill several times before. I think about my favorite parts of American history, for example the tradition of communal barn raising, whose products still dot parts of rural America. They are a vestige of the community spirit and mutual aid that once accompanied our vaunted individualism. As I rely on the kindness of strangers and friends, I hope that great American tradition of cooperation and concern for others will once again prevail.

Journalist Helen Epstein has published 10 books of nonfiction, most recently editing her mother Franci Rabinek Epstein’s Franci’s War.

Dear Helen, I have just finished reading your article cum confession and am full of admiration. There is no paralyzing fear or self pity, just a matter-of-fact accounting in your report. Your journalist persona has taken over your physical and mental person,

. I hope with all my heart that you will be well and healthy after you finish the treatment cycles. I will keep my fingers crossed . Yours Dita Kraus

Thank you Dita! You and your work are an inspiration to me!!!

Thank you for writing so thoughtfully about this moment of shared history and about the way public and private dangers collided for you in June 2020. My identical twin sister has just been diagnosed with cancer and like you faces sustained and difficult treatment in this treacherous era of Trump and Covid. I’m grateful for your article which is relevant and helpful to us both. I write as someone who is an avid reader of your books and who looks forward to reading Franci’s War. Thank you, Helen and may your treatments work quickly and completely.

Thank you Eleanor!!!

To Helen: Ever since you strode into the newsroom in Boston where I worked some time ago to tell me, excitedly, about the backstory of your research and writing about Joseph Papp, I have been impressed by the clarity of your vision and your indomitable spirit. I hope to greet you again in person soon, and to read more of your work going forward.

Helen,

Thank you for your clear, personally expressive narrative. I hope that your pain–both physical and mental, is/are behind you. I look forward to your future good health and your thoughtful vision. May your healing and your work continue to be a blessing.

Dear Helen,

As a colleague on the Fuse for some years, I’ve read your work before with interest and pleasure but never before have come away with such a sense of who you are. Low-key, aware of others, with an unshakable sense of proportion and a journalist’s eye. I hope that you continue to recover well, that the chemo isn’t too exhausting, and that we can meet for a latte some day.

I just finished participating in the zoom meeting sponsored by the Detroit Holocaust Center where you discussed Franci’s War. I became an immediate fan and was SO impressed with your authenticity, modesty, and articulate way of speaking. When you immediately disclosed you had cancer and was undergoing chemotherapy, I felt so sorry and worried as I was such a new “fan” and already felt affection for you. However, after reading your candid article about your recent diagnosis and treatment, I felt reassured that you will be ok. I have 3 brothers who are doctors and my late father was a Dr. so I know just a little, and I think you have a very good prognosis. You will deal with this with grace, I am sure. I can also add that our evil a President gives us something else to channel our despair and anger toward. Let’s do all we can to defeat him and his soulless supporters, so that all of our futures will be better.

Best of luck to you, and congrats on a great presentation. You allowed viewers to get to know you…