Opera Album: A Deliciously Grisly “Comic Opera” from 1789 — the Year the French Revolution Began

By Ralph P. Locke

Grétry’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue — the story of the original lady-killer, Bluebeard — receives its world premiere recording and it’s splendid.

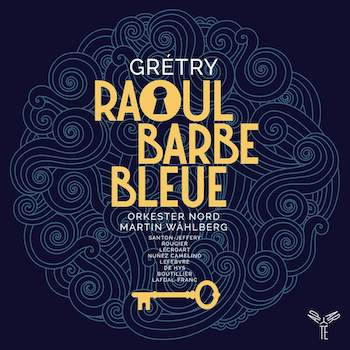

Andre Ernest Modeste Grétry: Raoul Barbe-Bleue

Andre Ernest Modeste Grétry: Raoul Barbe-Bleue

Chantal Santon-Jeffery (Isaure), François Rougier (Vergy), Enguerrand de Hys (Carabi), Jérôme Boutillier (Carabas), Manuel Nuñez Camelino (Osman), Matthieu Lécroart (Raoul).

Orkester Nord, cond. Martin Wåhlberg.

Aparte [2 CDs] 88 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

André Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741-1813) was born in Liège, which is now in Belgium, and studied in Italy before finally moving to Paris and becoming a French citizen. His operas, wildly popular in the late 1700s and early 1800s and (selectively) revived with some success toward the end of the 19th century, are hardly ever staged now and almost never outside of the Francophone realm.

Record collectors, though, have access to far more Grétry operas than are regularly performed. American Record Guide has reviewed no fewer than nine over the past two decades. I can particularly recommend the Zémire et Azor with Mady Mesplé (despite the 20th-century addition of recitatives, some of them with orchestra, in place of spoken dialogue); Le magnifique, recorded by Opera Lafayette; and La caravane du Caire, conducted by Marc Minkowski. Several of his operas take place in the Middle East, portrayed as variously exotic (fantastical in Zémire; dangerous and inhumane in Caravane).

Here we have what I gather is the first recording of his Raoul Barbe-Bleue (freely translated: “Count Raoul, Known as Bluebeard”). An opéra-comique (hence with spoken dialogue), it is set in France and based on a 1697 tale by the writer Charles Perrault, who also wrote “Cinderella” and other beloved nursery tales. The story—about a French count who murders each of his many wives—went on to be retold, and sometimes heavily reworked, in several later operas, notably by Offenbach, Dukas, and Bartók. (The Offenbach spoof was reportedly a response in part to Grétry’s work, which had been recently revived.) But Grétry did his version of the legend much earlier, and very effectively: in 1789, months before the outbreak of the French Revolution.

The story is of course grisly, and Grétry and the renowned librettist Michel-Jean Sedaine deserve credit for pushing the limits of the opéra-comique genre, creating at times quite a scary atmosphere. The work contains some lighter moments as well, primarily in scenes involving Raoul’s major-domo Osman (presumably a Turk)—who is portrayed as an elderly fraidy-cat—and in scenes involving the nobleman Vergy, who disguises himself as a woman in order to gain entrance into Bluebeard’s castle in hopes of saving his beloved Isaure. “La belle Isaure” is portrayed in a realistic, not idealized manner. She feels obliged to forgo marriage to Vergy and instead marry Bluebeard—a wealthy, menacing brute—in order to gain access to funds that will restore her (nasty) brothers’ properties and honor. And we see her repeatedly tempted: by visions of aristocratic finery (which prompt her to accept his hand in marriage) and, later, by Bluebeard’s mysterious locked room.

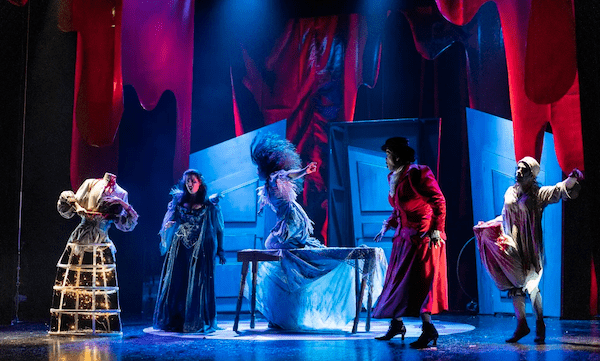

C. Santon-Jeffery, M. Lécroart, M. Nunez Camelino in the Norwegian production of Orkester Nord’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue. Photo: Leikny Havik Skjærseth

Bluebeard leaves Isaure alone for a while with a set of keys, pointedly inviting her to open any door but the one he points out to her. Tempted by the possibility of discovering riches, she opens the sole forbidden door. She is promptly and properly horrified to find the remains of wives one, two, and three, as is the disguised Vergy, who arrives soon after. The ever-nervous Osman, too, comes upon the scene and is terrified (he knows just how vengeful his master can be). Bluebeard returns, realizes what she has learned in his absence, and threatens to kill her. Vergy and Osman send a message (attached to the tip of an arrow) to the outside world. Three knights—the fathers of the dead wives—ride up to the castle, and Vergy shows them their daughters’ dead bodies. One of the knights murders Bluebeard (onstage, or just outside a door that we see), and Isaure and Vergy now are free to marry.

I was astonished to find how well this all works. Most of the numbers are relatively concise, yet often marked with unexpected harmonies, rhythmic figures, or turns of phrase. There are more extensive musical interludes as well. Isaure sings a particularly multifaceted aria as she tries on the jewels while considering whether to accept Bluebeard’s offer of marriage. Perhaps Gounod and his librettists had this scene in mind when putting together the Jewel Song for Marguerite in Faust (1859, rev. 1869; see my review of the world premiere recording of the 1859 version).

Even more complex and elaborate is the solo scene in which Isaure reflects sadly on how she has rejected Vergy in order to save her family’s fortune, then expresses curiosity about the forbidden room, and finally—while the orchestra plays a powerful, tension-laden passage—discovers what the locked room holds.

C. Santon-Jeffery, F. Rougier in the Norwegian production of Orkester Nord’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue. Photo: Leikny Havik Skjærseth

Indeed, throughout the opera the orchestra repeatedly sets the tone for a scene or particular confrontation. A very attractive march is heard three times in Act 1: somewhat folklike in tone, and entrancingly orchestrated. Toward the end of the trio in the third and final act, the orchestra evokes the cloud of dust and the sound of horses’ hooves, as the fathers of the three murdered wives gallop toward the castle. This trio (“Vergy, ma soeur”) is in fact my favorite number in the opera, both musically and dramaturgically. It takes place on three different levels of the castle. Isaure is in the main room, pretending to pray; Bluebeard, in an underground vault, is calling insistently for Isaure to join him to be put to death; and “Anne,” two steps above the stage, is looking out the turret window to see if the saviors that he sent for are arriving (and they are, as I just said). This number, with its constantly shifting musical material—in the three voices and in the highly responsive orchestra—was reportedly the one that “most caught the imagination of contemporary audiences.” I can readily see why. I hope Raoul Barbe-Bleue finds its way to the stage, or even to a semi-staged concert performance, sometime soon here in North America, once the Covid-19 pandemic is over. It would be a natural for such adventurous companies as Opera Lafayette or Boston’s own Odyssey Opera. Perhaps it could be done in an alertly phrased new English translation, so the spoken dialogue will make its full effect.

Matthieu Lécroart in the Norwegian production of Orkester Nord’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue. Photo: Leikny Havik Skjærseth.

I had never encountered Orkester Nord (formerly known as Trondheim Barokk) nor their conductor Martin Wåhlberg. Together they create an orchestral backdrop full of energy and varied colors. The players use period instruments, often bringing a welcome edge to the string and wind tone. The timpani make their presence felt through sharp rapping with unpadded sticks.

The singers help enormously. (You can hear the beginning of each track here.) The biggest role, that of Isaure, gives the rich-voiced Chantal Santon-Jeffery the opportunity to show a wide range of moods, not least in the spoken dialogue. My only complaint is that her long notes often have a slow throb. I have complained about this in recordings she has released of works by Félicien David and by Marie Jaëll.

Matthieu Lécroart is new to me, as are most of the others. He can use his powerful baritone seductively or scarily—just right for Bluebeard. The voice is a bit inflexible on quick notes, but the role requires little in that regard. He is splendidly frightening in spoken dialogue, as are the performers playing Isaure’s selfish, indistinguishable brothers. (Librettist Sedaine teasingly dubbed them Carabi and Carabas, names that rhyme with -ci and -là, word-endings that mean “the latter” and “the former.”)

François Rougier does a marvelous job with the tricky role of Vergy: he must be a credibly brave hero at the beginning and end, yet, in the middle scenes, be able to pretend to be Isaure’s sister Anne. As Soeur Anne, Rougier speaks in a falsetto that reminded me of Dustin Hoffman in the film Tootsie. His singing voice is occasionally unsteady; even so, he surely has a fine career ahead of him. Manuel Nuñez Camelino is hilarious as the aged major-domo; he adopts a slight foreign accent (or at times an exaggeratedly French one, with humorously long guttural R’s). Though he was born and initially trained in Argentina, he has apparently been in France since 2006. The rest of the cast consists of native Francophones, which helps the extensive spoken dialogue flow and fly.

The recording was made, under excellent studio conditions, in a church in Trondheim, Norway, and occasionally sounds have a somewhat heavy echo, but I could always hear details clearly. The sessions came soon after a run of staged performances elsewhere in Trondheim, hence the vividly dramatic tone of the whole. A five-minute video on YouTube (above) shows how imaginative and entrancing the sets, costumes, and stage direction were, and even shows the singers receiving instructions from a teacher of mime.

The recording can be enjoyed—a track at a time or entire—on various streaming services, such as YouTube and Spotify. But to get the booklet, which contains an excellent synopsis and essay plus the libretto—all in French and good English—you’ll have to purchase the CD or a digital download, or else subscribe to Naxos Music Library. A longer essay on the opera by the same writer, David Le Marrec, is found online (but in French only).

This Bluebeard is one of the most intriguing and fresh-sounding recordings ever made of a late-18th-century opera. I’d put it up there with Carlo Maria Giulini’s famous 1959 recording of Don Giovanni as a near-perfect realization of a work from that era. (On the challenges of achieving near-perfection in an opera recording, see my review of Christophe Rousset’s recording of Lully’s Isis.) I will treasure this, to me and most of us, new Grétry work and return to it often.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Aparte, Grétry, Martin Wåhlberg, Orkester Nord, Ralph P. Locke