Theater Review: “Heroes of the Fourth Turning” – What Lurks in a Zoom-screen Void

By Melissa Rodman

The play’s swift running give-and-take is chillingly beguiling, its myriad allusions arousing your curiosity as you consider the characters’ positions and conclusions yourself.

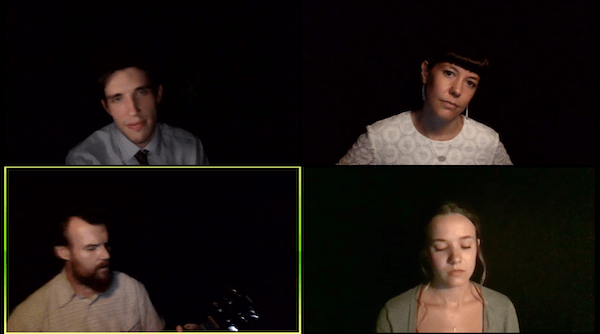

A screen shot of the Zoom presentation of Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning. Photo: Melissa Rodman.

Following a recent Zoom staging of his Heroes of the Fourth Turning, playwright Will Arbery tweeted that the endeavor was “an experiment in liveness on a tricky medium,” going on to note “the cast’s makeshift caves & moonlight rigs,” “laptops stacked on boxes and books — in bathrooms and bedrooms — windows blacked out — lamps and lightbulbs tilted just so.” Consider these new stage directions for the play, suggestions of what took place behind the scenes in the homes of the socially distanced creative team.

The Internet abounds with ways to create contactless theater during the pandemic, also providing the means for instant commentary. There are full productions, prerecorded in populated theaters and now streaming; readings that unfold in real time; and something in between, productions like this Zoom Heroes via Play-PerView, which was live as it engaged with playing with the medium of delivery. (For the record, the play also exists in another digital format — a 2019 videotaped performance of the Playwrights Horizons original — in the New York Public Library’s Theatre on Film and Tape Archive, currently closed. And readers can purchase the script online, too.)

Heroes, which was a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Drama, unfolds on one pitch-black Wyoming night after the 2016 election. Four young conservatives of varying convictions — Justin (Jeb Kreager), Teresa (Zoë Winters), Kevin (John Zdrojeski), and Emily (Julia McDermott) — linger outside a waning party. The event has been thrown in celebration of Gina’s (Michele Pawk) appointment as president of a small Catholic college, Justin, Teresa, and Kevin’s alma mater. Emily, who is Gina’s daughter, is afflicted with an unnamed illness and is visibly less enthusiastic than the three alumni. In the conversation she ventures tentative questions about who are, or can be, good people.

In one of several moments onstage alone with Emily, Justin, who is a bit older than the others, asserts that “this school makes 99 percent great people.” Justin holds fast to “stay[ing] among the like-minded,” waiting for the liberal tide to ebb, and he tries to assuage Emily’s doubts. “That feeling you’re feeling might just be because of Kevin and Teresa specifically as people,” he tells her.

And who are Teresa and Kevin “as people”? Teresa is in town just for the party, having moved east to Brooklyn and proclaims her hardline views wherever she goes. Drawing on rapid-fire, aggressive rhetoric, she knocks down any left-leaning notion, firing barbs like “there’s a war coming” with a toothy, sadistic smile. Kevin, for his part, flails about, both ideologically and literally. He indulges in navel-gazing (why doesn’t he have a girlfriend, for instance, is a repeated bemoaning), fidgets in-and-out of frame, and whines drunkenly on the topics discussed, which include the state of the US, religion, abortion, gender, pain, a culture war, and that persistent question of rectitude.

The intermissionless play builds and dwells throughout their two-hour conversation, propelled by various assertions, negations, directives, and debates. The characters buttress their talk with lots of name-dropping, intellectual and otherwise (e.g., Plato, Saint Augustine, Flannery O’Connor, Walter Brueggemann, Pat Buchanan, and Steve Bannon, to name a few). At one point, Teresa provides a vehement exegesis of William Strauss and Neil Howe’s theory The Fourth Turning, from which the play takes its name. The play’s swift running give-and-take is chillingly beguiling, its myriad allusions arousing your curiosity as you consider the characters’ positions and conclusions yourself.

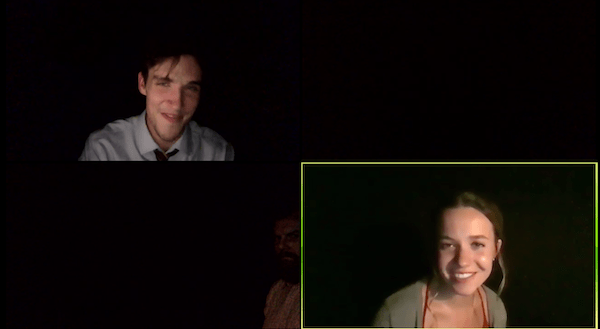

A screen shot of the Zoom presentation of Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning. Photo: Melissa Rodman.

Before the curtain — that is, laptop for me — was raised, remote attendees were provided with suggestions “for optimal viewing”: “turn your computer brightness up to full, turn off all the lights you can, crank your volume up.” I did as recommended, sitting alone on my carpet, my feet in socks, and near enough to a window to catch the evening light deepen to indigo as the play went on. Preshow — when the audience would have been ushered to our seats — a soundscape piped in through the small black screen in front of me, the nighttime wailing and cricketing of unseen fauna undercut by soft, warbling music.

One of the first lines read aloud via Zoom was, “There’s a lot of space,” a stage direction rather than a character’s utterance. And, as the actors made their individual entrances, exited, and returned to their respective Zoom quadrants, they toyed with their positions, lurking at the frame’s edge, even though it was impermeable to them. An unfortunate technological drawback: the neon-green box (can it be taken away for future streams of this, and other, Zoom plays?) that outlines the tile of whoever was speaking or emitted sound in their space. This vibrant beam cut through the “stage,” inevitably catching the viewer’s eye as it roamed in the carefully staged darkness of each background.

Other realities of the medium: the actors’ full bodies were truncated into busts that existed in the bounds of the computer (limited “space”), and the players looked directly at the viewer rather than at each other. But the actors’ expressive faces — this production featured the original Playwrights Horizons cast — pounced on their characters’ moments of remoteness and intimacy, modulated by an actor’s quiet tug of her cardigan here or the thrum of another’s guitar there. It was like peeking, unnoticed, into whatever flattened void the five performers occupied.

Melissa Rodman writes on the arts, and her work has appeared in Public Books and The Harvard Crimson among others.