Book Review: “The U.S. Antifascism Reader” — Recovering the Great American Tradition of Punching Nazis

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Practical handbook, compendium of theory, or history of an American tradition? A little of each … but enough of any?

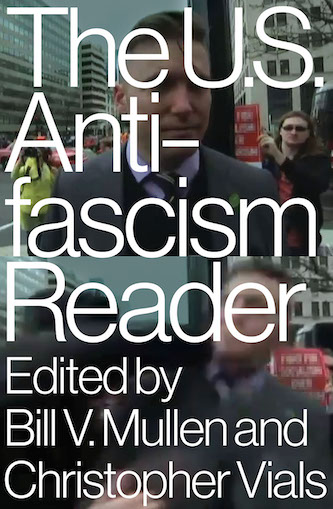

The U.S. Antifascism Reader. Edited by Bill V. Mullen and Christopher Vials. Verso Books, 384 pages, $29.95.

I write about this “antifascist” volume in the wake of Trump’s blasting of so-called Far-Left fascism at his Mount Rushmore rally on July 3rd. Among this book’s selections is an excerpt from Theodor Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality. Introducing the piece, editors Bill V. Mullen and Christopher Vials inform us that Adorno “originally wanted to call the study ‘The Fascist Personality’ but deemed this title too risky in the early Cold War context.” Be that as it may, they don’t mention Adorno’s later conclusion (found in his correspondence with Herbert Marcuse) that the “authoritarian personality” may indeed be rightist or leftist. That notion resonates with statement from Adorno’s pupil, Jürgen Habermas, that there exists a “Left fascism” — defined by a ‘voluntarism’ or ‘actionism’ which “makes a decisionistic start in the hope that retrospectively, after the successful fact, justifications will be found for the costs that have arisen.” In other words, a “kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out” philosophy of praxis.

I write about this “antifascist” volume in the wake of Trump’s blasting of so-called Far-Left fascism at his Mount Rushmore rally on July 3rd. Among this book’s selections is an excerpt from Theodor Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality. Introducing the piece, editors Bill V. Mullen and Christopher Vials inform us that Adorno “originally wanted to call the study ‘The Fascist Personality’ but deemed this title too risky in the early Cold War context.” Be that as it may, they don’t mention Adorno’s later conclusion (found in his correspondence with Herbert Marcuse) that the “authoritarian personality” may indeed be rightist or leftist. That notion resonates with statement from Adorno’s pupil, Jürgen Habermas, that there exists a “Left fascism” — defined by a ‘voluntarism’ or ‘actionism’ which “makes a decisionistic start in the hope that retrospectively, after the successful fact, justifications will be found for the costs that have arisen.” In other words, a “kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out” philosophy of praxis.

Thus it was with a strange feeling of coming full circle that, while reading this book, I caught the sound of antifascism coming out of the mouth of a millionaire demagogue in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Suffice it to say, then, that while I shed no tear that neo-Nazi Richard Spencer was punched in the face (subsequently slinking back into obscurity, hopefully forever), it becomes a matter of urgent concern whether we can articulate a nonauthoritarian antifascist position. So it will help to take a good look at how we got here in the first place.

There are many versions of the saying “When fascism comes to America…” It is usually (dubiously) attributed to Huey Long or Sinclair Lewis. And it can end with “it will be called antifascism” or “it will be wrapped in the American flag,” etc. With Trump, we can add a new version: “When fascism and antifascism come to America, they will present themselves in the form of the doppelgänger trope: ‘No, shoot him! I’m the real antifascism!’” It will be helpful to remember that we have been here before: during the 20th century, authoritarianism — versions from the right and the left — have competed for the term “socialist.” So we need a clear and accurate view of history, particularly one that serves up a solid understanding of crucial terms (fascism, etc). The U.S. Antifascist Reader sets out to provide that kind of chronicle, an overview of American Faschismustheorie. As the editors describe it, the German word “refers to an interpretation of fascism and its nature that guides one’s strategy and actions against it in the field.” As such, the ambition of the collection is threefold: identify fascism, describe its development, and articulate actionable plans to stem its tide (rather than, perhaps, merely “acting,” as Habermas might have it).

The selections are organized into five parts corresponding to historical periods, with each section containing works that try to meet the threefold ambition. While some works here clearly fall under the umbrella of antifascist, others are meant to illuminate popular and sympathetic attitudes to fascism in the national news media and beyond. The first section, the longest and perhaps most important, focuses on “US Antifascism in the Time of Dictators, 1932-1941.” Alongside opposition analysis from the likes of W. E. B. Du Bois and Sinclair Lewis (whose 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here imagines a fascist American dystopia), we also read excerpts from Barron’s and The Wall Street Journal that positively assess European fascism’s prospects for financial markets. There is also, in the vein of activism, the investigative reporting of Avedis Derounian, who infiltrated various far right organizations, and the 1938 program published by the American League for Peace and Democracy, the largest US antifascist network at the time. Charles “Father” Coughlin, a Catholic priest who was a notorious fascist apologist and anti-Semite, is here; so is antifascist Methodist minister and Soviet sympathizer Harry Ward. His piece, “Fascism and Race Hate,” reminds us of the long-standing antifascist strands in American Christendom, a perspective inspired by the oppression experienced by congregants. And that presages, of course, the well-known faith based activism of the Civil Rights movement.

Americans at the German-American Bund “Pro-American Rally” in 1933. Photo: US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives & Records Administration.

The second part, “Antifascism and the State,” traces the brief wartime period of antifascism as official state policy. It was “the period when the US government employed members of the Frankfurt School, then in exile mainly in New York and California, as intelligence analysts and propaganda experts.” This kind of official endorsement generated a sense of antifascism among generations of Americans, though that sentiment has recently been called into question. In part three we enter sketchier historical territory. The explosion of radical movements in the ’60s and ’70s, which emerged from underneath the country’s experience with anticommunism and McCarthyism, reflected the persistent memory of official antifascism. Many of these groups fought on various cultural fronts, such as race, gender, sexuality, class, peace, and democracy. There was not a focus on tangible fascist opponents. This shift reflected a move away from the broad Popular Front model of the past to a more fragmented approach taken throughout the American Left. Yes, this was the age of CIA-backed fascist coups in Latin America and beyond; but it also saw the birth of identity politics, a perspective that energized as well as inhibited the US Left. The editors include critical reflections on the preoccupations of “narrative” and “identity” in recent intellectual history. These include works that examine this tendency: “With all its limitations, all its watering down of radical redistributionist demands, multi-culturalism and the institutionalization of ethnic studies in education have nonetheless worked to blunt fascist appeals among large sections of the public, particularly among younger generations. But all the movements that generated the writings and writers of this collection had a hand in this blunting, as well.” And that notion of “blunting” points out a problem that we have today: we are disconnected from America’s earlier (and powerful) antifascist tradition. As Klansman Asa Carter and Jesse Mabry argue in “The Southerner,” identity politics is in no way inherently antifascist.

There is another historical break mentioned in the editors’ introduction, although it is not touched on in any of the book’s selections. Mullen and Vials explain that “the street-fighting mode of antifascism has a genealogy in the United States that predates the 1980s [including] the famous battle inside and outside of Madison Square Garden between antifascists and supporters of the pro-Nazi German American Bund in 1939.” Yet the ’80s suggest a parallel to that conflict: “‘Antifa’ as we know it is largely a post-1980 phenomena and a European import. In the newly reunified Germany, the term spread as a reference to punk and anarchist youth, with roots in squatter and subcultural scenes, who physically clashed with members of a resurgent neo-Nazi movement. The first major organization in the United States to form along these lines was the Minneapolis-based Anti-Racist Action in 1988, and it initially used the term “anti-racist” because its organizers saw “anti-fascist” as a word too dogmatic for an American context. In the 21st century, Americans from anarchist, radical, and subcultural scenes began mimicking the substance and style of their European counterparts even more directly. They borrowed the symbols and imagery of “Antifaschistiche Aktion,” the short-lived united front of socialists and communists who first organized in Weimar Germany and later in the postwar rubble of the Nazi regime. The importation of postwar German antifascism, the editors suggest, brings with it troublesome imitations. Part of this volume’s efforts, it must be assumed, is to move beyond Antifa’s debt of European influence, to cultivate homegrown antifascism.

German American Bund rally New York, Madison Square Garden, Febr 1939; from “The Nazis Strike” 1943. Wiki Commons.

So does The U.S. Antifascism Reader succeed in its threefold ambition? Far be it from me to criticize Mullen and Vials, two experts on the subject Also, to their credit, the pair avoid the trap of framing antifascism in a purely academic context: they usefully buck institutional intellectual trends by accepting historical materialism as their bedrock. Although it must be said that it is more than a little hopeful of them to envision an inspiring synthesis: our period of identity politics will become effectively antifascism once a historical materialist model has been accepted by the left. For them, our earlier antifascist sensibility (to unite disparate elements against common antidemocratic tendencies) “was not only to collapse distances across continents, but to move toward what we now call intersectional thought and action.” This is optimistic, as optimistic, perhaps, as those dreams that, with the arrival of the First World War, various nationalisms would unite under a socialist umbrella.

A critique of identity politics from the left is that the act of challenging naming and narratives — purely linguistic practices, however much they overlay economic realities — precludes challenging material conditions. An aspect of this impasse that pertains to antifacism was pointed out by Yuliya Komska in a Boston Review article last year, “In Search of an Anti-Fascist Language.” She writes: “While fascist rhetoric has been a subject of discussions almost continuously since the 1930s, and anti-fascism as a set of practices has never been more popular (witness the global rise of Antifa), an explicitly anti-fascist language is largely terra incognita…. It is possible to prune away all dog whistles, slurs, and dehumanizing tropes—and still not know what good language does, to whom, or why.” But such a language has existed. The challenge is that the most potent antifascist language was not that which served the objectives of distinct discourses among individual groups. A number of America’s national, religious, and ethnic organizations — although united in the name of democracy — crumbled under the weight of fascism.

Indeed, insisting that truth lies in a group’s discovering its identity (and insisting that others respect that discovery on the group’s own terms) is a hallmark of fascism itself. As Jessica Cassell has noted in her perceptive article “Marxism vs. Intersectionality,” the institutions of power that fascism relies on “often adopt intersectional language to mask the reality that they are not fighting for meaningful reforms.” So, rather than assume we should be engaged in a search for an antifascist language that dovetails with identity politics, we might do better to turn to what has worked in the past. And that tells us that antifascist language, at its most efficacious, drew its power from preexisting class analysis: from that understanding provided by historical materialism and its political extension, international socialism. I wonder if Mullen and Vials would agree with me on this: the next chapter in their splendid volume would welcome a return, warts and all, to “class-based” antifascist, prodemocratic language.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: antifascism, Bill V. Mullen<, Christopher Vials, fascism, The US Anti-fascism Reader