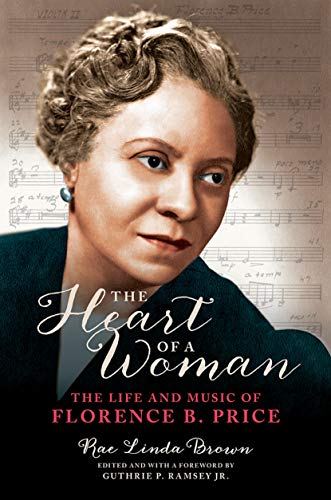

Book Review: “The Heart of a Woman” — The Life and Music of Florence B. Price, America’s First Important Black Woman Composer

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It wasn’t until 2009 that a trove of Florence B. Price scores was discovered in a dilapidated house in down-state Illinois and a revival of interest in this most remarkable of composers began in earnest.

The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price by Rae Linda Brown, edited and with a foreword by Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. (University of Illinois Press), 295 pp., $30.

There’s no doubt that Rae Linda Brown’s thoroughly researched, engrossing The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price would have been a welcome entry into the literature of American music had it appeared 20 years ago. But the book’s publication in 2020, as the United States seems on the cusp of a real reckoning with the complexities of its racist past on a number of fronts, makes this biography of the country’s first important Black woman composer particularly timely.

Not that Price had any pretensions about her place in the pantheon of American musical titans. Born Florence Smith in Little Rock in 1887, Price was, evidently, almost universally liked, but also reserved to a fault – a trait that Brown argues ultimately hindered the spread of her music’s reach during her lifetime.

Even so, Price was fortunate in many ways. Her parents were leaders in Little Rock’s then-robust Black middle class. Her father, James Smith, was a well-respected dentist as well as a community activist and, among other things, he passed his pride in his race to his daughter. Her mother, Florence Irene, was Price’s first music teacher as well as a businesswoman of conspicuous success.

Price took after both, excelling in music and academics: Brown writes that she initially wanted to pursue medicine as a career, but her father, recognizing the practical challenges standing in the way of a Black woman in early-20th-century America becoming a doctor, discouraged her. So in 1904, Price moved to Boston and enrolled at the New England Conservatory, where she completed a double-degree program – a performers diploma in organ and teachers certificate in piano – in just three (rather than the usual four) years.

Also while at NEC, Price began formally studying composition: her teachers included the Conservatory’s visionary director George Whitefield Chadwick and Frederick Converse. Her early works from her student days are now lost, but included chamber music and a symphony.

Following graduation, Price returned to Arkansas, teaching at several schools in and around Little Rock before becoming head of the music department at Clark University in Atlanta in 1910. This was a short-lived tenure, though: she returned to Little Rock in 1912 to marry Thomas J. Price, a lawyer, and raise their two daughters (a son died in infancy).

The advantages of Price’s life – marriage to a successful lawyer and a busy teaching studio, among them – couldn’t shield her or her family from Arkansas’s increasingly deadly racism. Indeed, her family’s social prominence seems to have drawn unwanted attention to them: after one of Price’s daughters was targeted for a retaliatory lynching in 1927, the family left Little Rock for Chicago.

It was in the City of Big Shoulders that Price’s musical career took off. She flourished in the city’s vibrant musical environment, expanding her command of composition, theory, and instrumentation at various local institutions including the Chicago Musical College, Chicago Teachers College, and the University of Chicago. She taught regularly and performed widely as a pianist and organist. And she finally achieved recognition as a composer: in 1932 a pair of Price’s scores – her Symphony in E minor and Piano Sonata – took high-profile prizes from the Wanamaker Foundation. The following year, Frederick Stock led the premiere of the former with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra during the Chicago World’s Fair, making Price the first Black woman to have a symphonic work performed by a major ensemble.

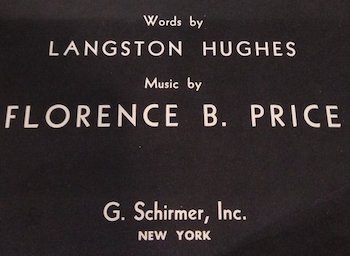

More music subsequently flowed from her pen: three more symphonies (one is now lost), a piano concerto, smaller orchestral pieces, piano works, choral music, and songs – including settings of Langston Hughes poems and various spirituals arranged for Marian Anderson, a dear friend.

And yet the last 20 years of Price’s life were often frustrating. While her music was performed widely in the Chicago area and, increasingly, around Michigan (the Michigan WPA Symphony Orchestra premiered her Symphony no. 3 in 1940 – the piece drew praise from none other than Eleanor Roosevelt, who happened by during a reading of two of its movements), acceptance from elite coastal ensembles never came. Indeed, one of the book’s most disheartening passages details Price’s efforts to enlist Serge Koussevitzky’s Boston Symphony in performing her music. Forty years after Chadwick provided her invaluable encouragement just across the street at NEC, Koussevitzky was unmoved: it wasn’t until 2019 that the BSO performed anything of Price’s (as fate would have it, that occasion featured three movements of the symphony Price was urging Koussevitzky to program in 1944).

By the time of her death from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of sixty-six in 1953, Price’s career seemed to be on something of an upswing, though: John Barbirolli had recently performed some of her music with his Hallé Orchestra and more opportunities abroad seemed in the offing. Instead, near-oblivion followed: it wasn’t until 2009 that a trove of Price scores was discovered in a dilapidated house in down-state Illinois and a revival of interest in this most remarkable of composers began in earnest.

Of course, Brown had been one of Price’s biggest cheerleaders for some time by then: she first encountered the manuscript of her Third Symphony while a graduate student at Yale in 1979 and spent much of her career (tragically, she died of cancer in 2017) advocating for this forgotten figure in American musical history.

So what has she left us? A foundational document, to be sure: stitching together Price’s life seems to have been no easy task. Price’s papers, such as they are, were scattered and (as the late discovery of so many manuscripts attests) incomplete.

Indeed, there are holes in the present narrative. What happened to Price’s younger brother, Charles? Brown wasn’t able to find out, though he’s omitted from Price’s significant biographical documents (including the passport application she filled out shortly before her death). Or Price’s first husband (they divorced in 1931)? Again, the trail runs cold: he was apparently a guest of Price’s at a concert in 1935 and died in the early 1940s – though Brown casts some doubt on the plausibility of the former (he was abusive and their divorce contentious) and found no evidence to support the latter claim.

More crucially, there seems to be a lack of first-hand documentation – letters, diaries, and whatnot – for whole stretches of Price’s life. This isn’t necessarily surprising, given when and where she lived, though it does present some literary challenges.

What Brown opted to do, in light of these missing pieces, is ingenious and deeply rewarding: she fills in the biographical holes with a mix of musical analysis and cultural context that is both fascinating and revealing.

Price was no musical rabble-rouser, that’s for sure: her symphonies that survive are each modeled (rather strictly) on Antonin Dvorak’s New World Symphony, and her love for the Romantic keyboard repertoire of Liszt, Schumann, Brahms, and others permeates much of her piano, organ, and vocal music.

Price was no musical rabble-rouser, that’s for sure: her symphonies that survive are each modeled (rather strictly) on Antonin Dvorak’s New World Symphony, and her love for the Romantic keyboard repertoire of Liszt, Schumann, Brahms, and others permeates much of her piano, organ, and vocal music.

But Brown is keenly aware of the African-American musical influences Price drew on and she illuminates them consistently. Both the Symphony no. 1 and 3 receive chapter-length analytical treatment and, while Brown employs some theoretical terminology in each, she’s also got the gift of being able to explain musical effects in succinct layman’s terms. Thus, one comes away from the book with a strong sense of what Price’s music sounds like (though few recordings of much of her music presently exist).

Price’s compositions, as Brown points out, utilized a host of musical characteristics often associated with Black musical culture – call-and-response figures, exotic percussion instruments, and expressive rhythmic figures, among them – as well as nuances of organ registration and choral music drawn from Price’s long experience playing in (and writing for) the Black church. Yet, in its formal structure, harmonic language, and instrumentation, Price’s music was almost insistently rooted in the traditions of the 19th century. To be sure, then, her corpus is singular and distinct from those of her contemporaries like William Grant Still (who was a childhood friend from Little Rock) and William Dawson.

Valuable as Brown’s musical discussions are, there may be even more practical benefit – these days, especially – in her ability to bring to life the richness of Black culture from the late-19th to the mid-20th century. Simply put, despite colossal obstacles, there was a flourishing arts scene for Black writers, poets, actors, dancers, musicians, and composers. Price’s life unfolded in the midst of this, especially after she relocated to Chicago.

True, she’d always been a part of vital academic and intellectual circles, going back to her time as a child growing up in Little Rock. Yet it was in Chicago that Price came into her own, taking leadership roles with the local chapter of the National Association of Negro Musicians, the Chicago Music Association, and various other musical cooperatives. Her circle of friends and champions at this time ranged widely, from the diva Marian Anderson and the CSO’s Stock to the celebrated tenor Roland Hayes, pianist Margaret Bonds and her mother Estelle, and conductor Valter Poole.

Even so, Price was a Black woman in 20th-century America and Brown reflects openly on the racist headwinds she faced down, both in Jim Crow-era Arkansas and pre-Civil Rights Movement Chicago. The acceptance of her music by mixed-race audiences, for one, didn’t translate into broader gains for her or the larger African-American community. Yes, Price integrated – apparently without much difficulty – some of the Chicago music clubs she joined. And her move north of the Mason-Dixon line meant a considerable broadening of opportunities for her, professionally and educationally.

At the same time, Chicago proved, in some ways, just as backwards as Little Rock: Brown relates the experience of tenor Hayes, a star on WGN radio programs, whose skin color was kept under wraps for fear of offending the station’s large, national audience. Then as now, moral cowardice – especially where money or power are involved – was easy.

Against this backdrop, Price’s strength of character and perseverance stands out impressively. Yet her story isn’t entirely unique: systemic abuse, professional ups and downs, financial challenges, and failed relationships are the stuff of countless millions of lives. Price’s striving to rise above her circumstances, in Brown’s telling, results in the composer coming across as something of an early archetype of Black feminism, the traditional cast of her music notwithstanding. Given all the context Brown provides, that’s a hard argument to dispute – and, because of that, The Heart of a Woman proves to be a compelling bit of scholarship.

In addition to the vigorous, intricate portrait of a musician neglected through no single fault of her own, Brown has given us a stirring glimpse of a rich cultural life that existed largely apart from the traditional artistic power centers on the East Coast over the first half of the last century. In particular, Brown’s discussion of the courage, resilience, and breathtaking creative accomplishments of the African-American population from Reconstruction to the 1950s is absorbing.

Florence Price at the piano, 1941. Photo: Arkansas Educational Television Network

Some of the names of its leading lights – Harry T. Burleigh, William Grant Still, Langston Hughes – may be familiar; many more, now, are just footnotes. But, as Brown reminds, they all form a vital part of the United States’s cultural history (and her narrative hardly even contends with the more familiar popular genres of the time). In bringing them to life, Brown has provided a quiet but potent rebuke to the populist drivel from today’s political right that seeks to diminish, ignore, or whitewash the considerable contributions of artists of color to our national story. And she accomplishes that in the simplest, yet most effective, way: by presenting facts.

Appropriately, such an approach honors both Price’s lifelong commitment to education and Brown’s career as a scholar. Indeed, The Heart of a Woman is a book that educates in the best way: by bringing to life in bold strokes Price, her contemporaries, and her times. As such, it stands as a fitting capstone to Brown’s decades-long devotion to her subject and, more broadly, gives voice to the rich complexity of the African-American cultural experience.

Jonathan Blumhofer’s analysis of Price’s Mississippi River Suite.

Black poet and playwright Georgia Douglas Johnson‘s “The Heart of a Woman”:

The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,

As a lone bird, soft winging, so restlessly on,

Afar o’er life’s turrets and vales does it roam

In the wake of those echoes the heart calls home.

The heart of a woman falls back with the night,

And enters some alien cage in its plight,

And tries to forget it has dreamed of the stars

While it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Florence B. Price, Rae Linda Brown, The Heart of a Woman