Book Review: “Pizza Girl” — Savor Every Bite

By Melissa Rodman

In her novel Pizza Girl, Jean Kyoung Frazier has given us an exhilarating spin on a long line of road-rebel mothers.

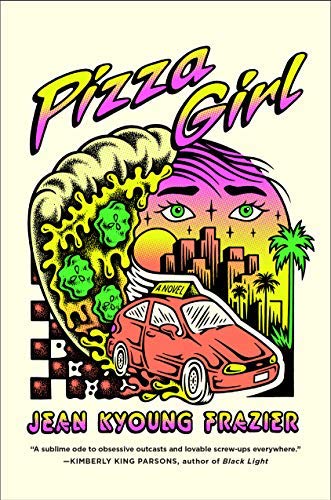

Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier. Doubleday, 208 pages, $24.95.

Stories about women and the open road have strong ties to the postwar American worship of the automobile. Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique (1963) examines the contradictory values American women juggled in the aftermath of World War II: the demands of motherhood and domestic responsibilities for husband, home, and children, on the one hand, and ambitions for education, careers, and independence, on the other. Either side of this calculus — dropping the kids off somewhere versus heading to school or an office — called for access to a car.

Fictional portrayals of women who felt trapped as mothers often celebrated cars as a means of escape. Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (1952) focuses on the fiercely independent Carol Aird, who expresses fondness for — but distance from — her daughter. When Carol embarks on a westward road trip with her lover, Therese, the car distances her from a looming divorce, though the custody battle calls Carol’s role as a mother into question and cuts her trip short. In Joan Didion’s novel Play It As It Lays (1970), protagonist Maria Wyeth’s compulsive (and self-destructive) need to drive is an attempt to break away from her troubled past and disintegrating family.

Cars, and the possibilities and limitations yoked to driving, have been integral pressure points in American fiction. Who can, and who can’t, take to the road? What do they find there, and what do they leave behind?

It is not a huge leap now to include Jean Kyoung Frazier’s debut novel Pizza Girl in this company, and that is not only because of the protagonist’s loaded relationship with a ’99 Ford Festiva (more on that later). The volume offers a compelling blend of humor and ache anchored in the stream of consciousness of its 18-year-old narrator, dubbed Pizza Girl by one life-changing customer, Jenny Hauser. Pizza Girl goes about her delivery routine at Eddie’s pizza shop in suburban Los Angeles and thinks about her mother, boyfriend, and father (the latter, an alcoholic, is deceased), and confronts the fact that she is 11 weeks pregnant.

While her mother and boyfriend are delighted by the pregnancy, Pizza Girl lives in a different world. She is fixated on past hurts and obsessed with undefined dreams and insecurities, some of which come into focus when her former classmates step into Eddie’s for takeout. “They could support a teenage pregnancy, but not this, not a person who drifted from one moment to the next without any idea about where she was headed,” she thinks. “[T]hey’d stare at the bridge of my nose, the gap between my eyebrows, the center of my forehead, anywhere but my eyes, a place where their own insecurities might be reflected back to them, murky in the brown of my irises.”

Hauser is new to the neighborhood and desperate to feed her young son, who wants to move back to Bismarck, where, among other favorite things, there is a restaurant that serves pepperoni-and-pickles pizza. Pizza Girl saves the day by coming up with the pie — dashing to the supermarket to secure the unusual topping and delivering it to Hauser. Their relationship develops, propelled by an undeniable affinity that becomes an obsession for Pizza Girl. In Hauser she sees an unconventional ideal: past lives and poetry, grace and grit, motherhood and lost momentum.

Frazier plumbs the depths of Pizza Girl’s mind, sketching what she finds there with heartfelt candor. “So many landscapes to picture her in,” Pizza Girl reflects after Hauser shares details about where she’s lived and what’s she’s done:

Her ponytail riding the subway, pushing through bodies and bodies on crowded sidewalks, surrounded by buildings so high she’d have to tip her head backward to see the tops of them. Her ponytail on a beach, salt and sunshine soaked into it. Among dark suits and conservative ties with the Washington Monument looming behind her. Hiking through forests in a haze of mist.

The text is fascinated with movement in ways that evoke women and the road narrative. It is embedded in Frazier’s language, which whirls about even when her characters are stationary, and especially when we ride with them in cars. Frazier’s Pizza Girl, like Highsmith’s Carol or Didion’s Maria, experiences painful tension between her dream of motion and the reality of stasis. And that is where the Festiva figures in. Beaten up but still running, the car passed from her father and then to her mother after his death. Now it is Pizza Girl’s. Predictably, she mulls over her dad’s flaws as she sits in the Proustian driver’s seat — but she also uses the vehicle to test her own agency, sometimes recklessly so.

The motif of the highway is sprinkled throughout the novel. It is a seductive testing ground. “I’d hopped into the Festiva and sped down the 5 North,” she recounts. “There was a high that came with being on the open road, alone, seeing Los Angeles fade behind me, the twinkling city lights burning out slowly.” The pregnant Pizza Girl ends up taking us on a whirlwind of a drive; Frazier has given us an exhilarating spin on a long line of road-rebel mothers.

Melissa Rodman writes on the arts, and her work has appeared in Public Books and The Harvard Crimson among others.