Arts Commentary: Consider the Self — I am George Floyd. I am Derek Chauvin.

By Patrick Conway

I am Derek Chauvin, and I am George Floyd. Who are you?

George Floyd inspired Street Art in Mauerpark (Berlin). Photo: Wiki Common.

Perhaps it’s because I teach writing in prison, but in times like these — as our cities burn after the senseless and horrific murder of a black man who died under the knee of a white officer — I tend to turn toward American literary traditions. Within them, there is likely no bigger figure than Walt Whitman. At one level, it seems silly to look toward a white poet from the 1850s when the experiences of black Americans should be front and center. But Whitman’s influence extends through time, creating a lineage that transcends individual identity, from Langston Hughes to William Carlos Williams, Simon Ortiz to Martín Espada, Adrienne Rich to Allen Ginsberg. Neither is his influence bounded by national borders. Many international poets — Pablo Neruda most famously among them — cite Whitman’s effect on their work.

I find myself returning to Whitman’s celebrated poem, “Song of Myself.” The epic is unabashedly about me, myself, and I (few other poets refer directly to their own names in their poems, but “Song of Myself” discusses “Walt” at great length). The poem contains a lot — multitudes, as Whitman would say — from reflections on mortality and human sexuality, to meditations on world religions (Islam, Hinduism, Puritanism, Christianity, and Native American religions all included). In light of the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing protests and riots, the parts I have focused on most are within Whitman’s famous lists, his cataloguing of American people, places, and things. For those familiar, these lists are predictably long and wide-ranging. He envisions the United States as a unified whole made out of disparate parts. But it isn’t just America that he aims to unify, it is also he, himself — Walt Whitman — whom he aims to unify: “Such as it is to be of these more or less I am, / And of these one and all I weave the song of myself.” Disparate but whole: what makes up America, what makes up the self.

Whitman “absorbs” archetypes of people, claiming they make up part of his identity, and that he in turn makes up part of theirs. The lists at first are without controversy (we get it, Walt — you are the lumberjack, the doctor, the sailor, the salesman, the beggar). They shift at points, however, rather quickly. He claims he quite literally is everyone: the slave, as well as the slave trader, the drug user, the sex worker, the policeman, the “lunatic.” He accepts all of them as part of his own identity: “Whoever degrades another degrades me, / And whatever is done or said returns to me.” About the only type he views unkindly are those who “laugh” and “jeer” at a sex worker (perhaps these are the same we would today call trolls), claiming their actions are “miserable.”

To say we’re all interconnected and part of the same whole is easy in the abstract, the type of platitude welcomed by happy nods. But to actually claim someone as odious as a slave trader is part of me, of who I am, is harder to accept. Particularly as a white man who has worked in my career to help fight against the injustices of the justice system, I recoil at that thought and want to distance myself from it immediately. On the other hand, to recognize that the same craven impulses, the same human failures, the same potential for evil that exists in others must also have the capacity to exist within me makes it all the more necessary to pay attention to my own inner decision-making, to interrogate my motivations and impulses. Identifying with others doesn’t mean I countenance their actions. If anything, it makes me want to rebuke them all the more, and understand them so I can hope to change them.

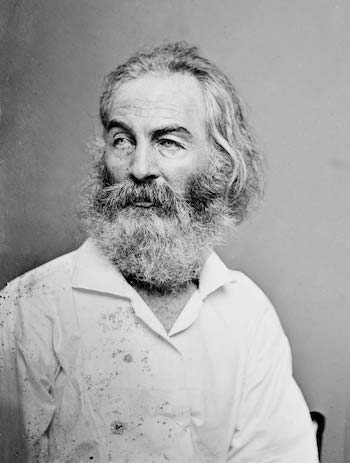

Poet Walt Whitman. Photo: Mathew Brady.

The justice system needs serious reform, but it doesn’t all come down to the winning of legislative victories. The problems that have led to George Floyd’s death and the subsequent protests and riots go deeper. Reducing prison populations, eliminating mandatory minimums, and restructuring policing tactics are important steps, and many good people continue working toward those goals. But if these horrific scenes are to end, it requires more than the “sanding down of rough edges” (as legal scholar Joseph Margulies says). It requires a different organizing principle. It requires treating others as though they are part of ourselves — for, as Whitman suggests, they may in fact be.

The number of white people quick to pronounce their “white privilege” rankles me at moments like these, at a time when black lives are being lost at the hands of the state (a state which for a long time has been run almost entirely by white men). It’s not that I believe being white doesn’t come without certain obvious privileges, it’s that merely acknowledging a vague recognition of it seems a shorthand way to appear as if one gives a damn without actually putting in any effort. To view others in the way that Whitman describes is hard work, more difficult than reciting a line about privilege. It means organizing ourselves around principles that aren’t self-serving, expedient, or trendy, but instead bend toward justice.

The first step, it seems to me, is to view others as an integral part of ourselves, lives disparate from our own but part of the same whole. That isn’t easy, but it may put us on a better path. As Whitman says, I “am not contain’d between my hat and boots.” I am the protestor marching in the streets, longing for justice. I am the rioter sowing chaos, bending low to light the fuse. I am the Trump voter, the Biden voter, and the disaffected nonvoter. I am the frightened police officer with kids at home, wincing at every pop and bang, fearing the sound of the call to advance. I am the police officer standing right beside him, eager to inflict pain. I am the black mother at home, watching every update on TV, proud but scared that her children have joined the protests.

And, lastly, and most difficult of all: I am Derek Chauvin, and I am George Floyd.

Who are you?

Patrick Conway is a former criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, DC and Boston, and a current doctoral candidate at Boston College researching the implementation and expansion of higher education programs in prison. His writing has received recognition from the Best American Essays anthology, and an article of his on the involvement of higher education in prison will be included in a forthcoming issue of the Harvard Educational Review. He can be reached on Twitter @PFConway30.

Tagged: Derek Chauvin, George Floyd, Patrick Conway, Song of Myself

Fantastic. Very thought provoking.

Good job Pat! Very well put.