Book Review: “The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien” — Ignoring the Poetry

By Clea Simon

As a series of speculative essays – outtakes, perhaps, from John Garth’s earlier work – The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien could have made an enjoyable browse, especially illustrated with the site-specific photos and Tolkien’s own work.

The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien by John Garth. Princeton University Press, 208 pp., $29.95.

“He that breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom,” says Gandalf the Grey in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The wizard, who serves as the repository of historical wisdom in the epic, is sparring with Saruman the White, his superior in the order of wizards. Saruman has “broken” his signature color into a rainbow of hues, symbolizing his break with the order’s underlying principles in his search for more power.

John Garth quotes this line in the introduction to his new book, The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien: The Places That Inspired Middle-Earth. He’s also guilty of it. Clearly a painstaking scholar, the author of the much more comprehensive Tolkien and the Great War ignores the poetry and creativity underpinning Tolkien’s classic, dissecting it in an over-thought (and, at times, overwrought) search for connections to the author’s real-life experiences from his earliest youth in South Africa, his upbringing in England, and the horrors he survived in the trenches of World War I.

Too often, Garth assumes causality. While many of Tolkien’s influences appear obvious, Garth’s certainty is, at best, galling. Yes, after his earliest youth in South Africa, the verdant green of England most likely suggested the green of the Shire. And, of course, Tolkien’s experience in the trenches probably played into his description of Mordor, with its ash pits and blasted earth. But in his attempt to pin every created scene down to one specific real-world reference, Garth does the artistry of Tolkien a disservice. “The Shire is a reflection of Sarehole,” he states early on, placing the hobbit’s home definitively in the English country village where Tolkien lived before going off to school. “Tolkien’s own version of a spider bite came from one of the lice that were an inescapable part of frontline life,” Garth posits. In fact, Tolkien was invalided out with louse-born trench fever, but Garth provides no documentation supporting this direct relation between the real illness and the fictional insect bite.

While Garth occasionally soft-pedals his connections – “Tolkien’s description of the Cross-roads trees … suggests Western Front scenes,” he says at one point – more often he stakes his claims as if they were fact. If fiction were just renaming and reconfiguring personal history, it would be a lot less rich. One of the ongoing discussions among the Inklings – which included C.S. Lewis, whose Chronicles of Narnia presents a Christ-like lion – was on the use of allegory. Garth, otherwise an impressive scholar, must have missed this period of Tolkien’s life.

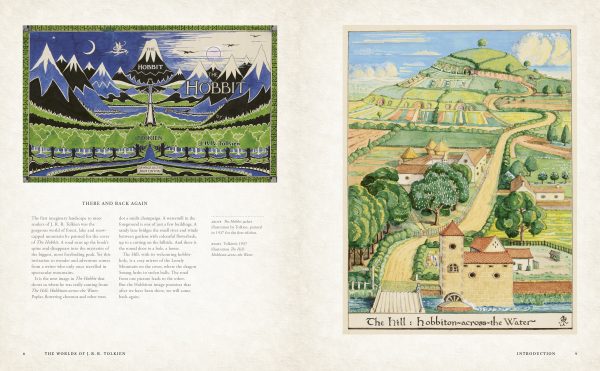

This is a beautifully produced book, replete with illustrations. Full-page photos of evocative landscapes are supplemented by both maps and smaller shots detailing architectural features, while many of Tolkien’s own paintings – his own maps and illustrations for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings – make this a lovely keepsake for fans. Less lovely are the multiple illustrations by lesser artists, which undercut the author’s own imaginings.

Pages from The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien. Photo: Princeton University Press.

In fact, these middling watercolors and sentimental drawings only serve to support this reader’s suspicion that padding was required to justify a $29.95 cover price. This is a short book, barely clearing 200 pages despite copious endnotes, as well as an index, bibliography, and acknowledgments, more an essay than a full manuscript. However, even within its brief main text, Garth repeats himself. An incident in Ithilien, when Sam and Frodo find themselves face-to-face with the severed head of a statue, comes to mind. In the book, the two are making their way across the former garden spot, which has been overtaken by the enemy. As they pass a statue of an ancient king, which has been beheaded, the sun breaks through, illuminating the severed head, which has flowers growing on it. “Look, Sam!” Frodo cries out. “The king has got a crown again!” It’s a lovely moment, exemplifying the persistence of hope. But in Garth’s hands, it comes up as an allusion to the vainglory of “Ozymandias,” as well as a reference to a World War I site, Crucifix Corner, among several other mentions in the brief text.

As a series of speculative essays – outtakes, perhaps, from Garth’s earlier work – The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien could have made an enjoyable browse, especially illustrated with the site-specific photos and Tolkien’s own work. Packaging it as a definitive work does Tolkien no harm, but it does the underlying scholarship, as well as Garth, a disservice.

Clea Simon’s most recent novel is An Incantation of Cats: A Witch Cats of Cambridge Mystery. She can be reached at www.CleaSimon.com.

Tagged: Clea Simon, J. R. R. Tolkien, John Garth, Princeton University Press