Opera CD Review: A Compact, Powerful New Opera from Carlisle Floyd, Composer of “Susannah”

By Ralph P. Locke

Prince of Players is based on a play that also yielded the movie Stage Beauty, and it’s one of the best new operas to come along in years.

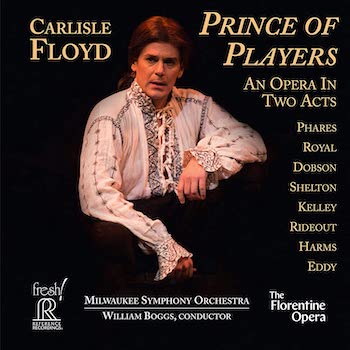

Carlisle Floyd: Prince of Players (opera in 2 acts)

Kate Royal (“Peg” Hughes), Rena Harms (Nell Gwynn), Chad Shelton (King Charles II), Frank Kelley (Sir Charles Sedley), Val Rideout (Villiers, Duke of Buckingham), Keith Phares (Edward Kynaston), Alexander Dobson (Thomas Betterton)

Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Florentine Opera Chorus, cond. William Boggs

Reference Recordings FR-736 [2 CDs] 96 minutes

Ninety-six minutes is short for a two-act opera on a serious subject, but it feels just right in Carlisle Floyd’s thirteenth and latest opera, Prince of Players. The plot zips along, clearly delineated in the sung text and stage directions. (The booklet helpfully provides the complete libretto, though in small font against a gray background—tough for my aging eyes.) Even better, the composer and the generally fine singing cast sharply differentiate the characters in vocal manner. And the basic story is a fascinating one, full of present-day relevance. In short, this opera works. I welcome it and wish it a long life.

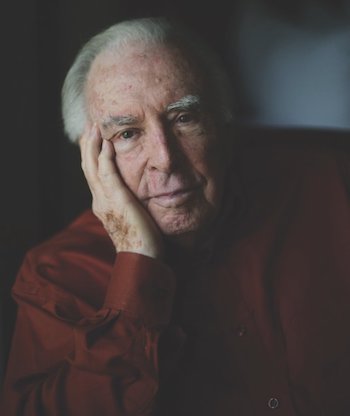

The name Carlisle Floyd (born 1926) is familiar to music lovers mainly because of his best-known opera, Susannah, which transplants the story of Susannah and the Elders (found in the Apocrypha) to the American South in the early twentieth century. Even people who have not heard or seen Susannah may well know its most famous aria, “Ain’t it a Pretty Night?” (as recorded by, among others, Renée Fleming). There is no solo moment quite so captivating in Prince of Players. But the new work is perhaps even more successful than Susannah at presenting and interweaving numerous vivid cast members in a plot that never lags or sags.

The libretto, written by the composer, derives from a play by Jeffrey Hatcher, Compleat Female Stage Beauty (1999), which was also adapted for a film starring Billy Crudup and Claire Danes (Stage Beauty, 2004). In all three incarnations of the story, we encounter the Stuart-era actor Edward Kynaston (ca. 1640-1712), at the point when his career is in jeopardy: he is renowned for playing women’s parts, but King Charles II is keen to change stage custom so as to allow his mistress, Nell Gwynn, to act upon the stage. This much is largely true to history, but the specific motivations and interactions of the characters have been freely imagined, and some characters are invented for the purpose, including rowdy crowds in scenes taking place at the theater and in a pub.

The plot balances out declining fortunes and rising fortunes. Kynaston’s dresser, Margaret (“Peg”) Hughes has been watching Kynaston’s artful acting for years. Now, with the king’s edict forbidding any He to play a She, Peg gets her chance to go on stage herself. Intriguingly, if perhaps anachronistically, Peg announces that she will play female roles more realistically, less idealistically, than Kynaston ever did—since she has a better sense of a woman’s complex feelings. And Kynaston, after some initial defensiveness, helps her realize that vision for the role of Desdemona, encouraging her to muss her hair, remove half her greasepaint, and show spunk instead of docility. Kynaston’s travails redouble when his aristocratic lover, Villiers, breaks off the relationship: “I’m . . . getting married into an old distinguished family, and a whiff of scandal and I’d be disowned. . . . I can’t risk . . . not having a farthing.”

Michael Kelly and Maeve Hoglund in Carlisle Floyd’s Prince of Players at the Little Opera Theatre of NY. Photo: Tina Buckman.

Most intriguingly, the opera is framed by two very different renditions of the murder scene: the first with Thomas Betterton as Othello and Kynaston in his long-admired role of Desdemona (which he plays with high decorousness, and with a delicate half-voice on a few high notes), the second with Kynaston tackling the role of Othello despite his lack of experience in male roles and with Peg rising ably to the challenge of Desdemona. Floyd’s music is quite different the second time around, with more active melodic interjections from the full orchestra, as if the two actors’ determination to play the scene in a gutsier emotional way has also brought premonitions of opera of two centuries later. Floyd’s music never imitates the most famous setting of this scene, namely in Verdi’s Otello; but it does feel like an hommage more generally to the beloved operatic repertory as a whole.

Indeed, throughout Prince of Players, the musical style feels keenly appropriate to the onstage events and emotions in very traditional yet always fresh-feeling ways. Whereas “Ain’t it a Pretty Night?” seems closely modeled on music of Barber and Copland, the allusions here are more diverse. I thought I picked up echoes of Janáček at times (particularly the latter’s Sinfonietta—a work for orchestra, no voices), but also gestures that recalled (without, again, copying) the keening high strings in Britten’s Peter Grimes. Plus there are slightly skewed numbers for performances in the pub (one of which is a raunchy song trumpeted by Kynaston in garish female drag — but sung in his normal range, not in falsetto — soon after the edict has chased him out of the theaters). Emotionally rich orchestral interludes bridge the scenes, much as in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, though sometimes more closely resembling, in feeling-tone, the interludes in Italian verismo operas such as Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (as at 13’45” in Act 2, Scene 4).

If all of this makes the opera sound like a pieced-together mess, I stress that it is not. The linkages and contrasts are all artistically planned and carried off with aplomb and naturalness. The total result is far greater than the sum of its parts. Prince of Players comes complete with several highly effective aria-like solos, a natural-enough inclusion in a libretto evoking the soliloquy-rich theater of seventeenth-century England. Some of these could function well as recital items. More importantly, the opera as a whole, I predict, will hold the stage for years to come. It is available in two versions: with chamber orchestra (first performed at Houston Grand Opera, 2016, where it was hailed by critics), and with full orchestra (first performed by Florentine Opera in 2018 with the performers heard here). A 2017 production by Little Opera Theatre of NY (at the Kaye Playhouse) — using the chamber version (31 players in the orchestra) — was described as “engrossing” and “moving.”

Composer Carlisle Floyd. Photo: AE Gateway.

The recording quality, from Uihlein Hall in Milwaukee’s Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, is generally fine, as one has come to expect from Reference Recordings. The performers are all adroit and communicative. Baritone Keith Phares sings beautifully and makes his words clear at all times. His dignity helps us care about his fate. Bass-baritone Alexander Dobson is rock-solid as Thomas Betterton. Tenors Chad Shelton, Frank Kelley, and Vale Rideout all nail their characters, though the latter two tend to wobble. Soprano Kate Royal is generally superb as “Peg” Hughes, sometimes floating tones that are at once delicate and firm. Unfortunately, when she is singing high and intensely, a slow throb undermines clarity of pitch and diction. Still, with a libretto in hand, one can appreciate her vision of the role, which is as central to the opera as the role of Kynaston.

Phrases and climaxes are shaped with a steady, responsive hand by conductor Williams Boggs. Though the recording was made during performances, audience noise is minimal. Bravo to the engineers!

I commend Carlisle Floyd’s latest opera to the attention of all lovers of the genre, and for that matter of Shakespeare. We have here an admirable attempt, on the part of a modern composer, to do justice to the dramatic vision of Shakespeare, at times using Shakespeare’s own language. Anybody who finds Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream fascinating or has been enchanted by Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Sir John in Love (which sets large swaths of The Merry Wives of Windsor to apt music, though adding various folk songs and other celebratory numbers) will find Floyd’s Prince of Players a worthy successor.

This is surely one of the best new operas to have been launched in recent years. Happily, it is available in full on YouTube, Spotify, and other streaming services, and the booklet is available online for free (so you can make it bigger on your screen and thus easier to read!).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second is also available as an e-book. He contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, Bilbao, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Carlisle Floyd, Jeffrey Hatcher, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Prince of Players, Ralph P. Locke