Classical CD Reviews: “Whither Must I Wander,” “Death and the Maiden,” and Caroline Shaw’s “Is a Rose” & “The Listeners”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Whither Must I Wander, the debut recording from baritone Will Liverman and pianist Jonathan King, is one of 2020’s finest classical releases; 12 ensemble provides a kinetically-played example of a large-ensemble arrangement of chamber music; Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra showcases two pieces by Caroline Shaw.

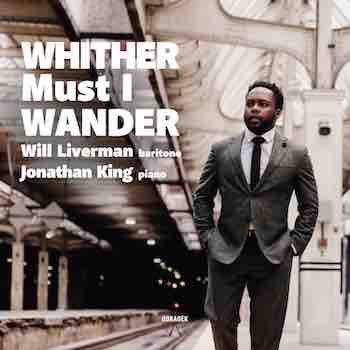

I’ll just come out and say it: Whither Must I Wander, the debut recording from baritone Will Liverman and pianist Jonathan King, is one of 2020’s finest classical releases. A concept album that focuses on themes of journeying, it’s at once impressively thought through, refreshingly programmed, and executed with a degree of musicality that’s breathtaking.

Liverman, who recently made his Metropolitan Opera debut, is a major find. His instrument calls to mind Gerald Finley’s for the focus and richness of its tone, as well as the excellent clarity of his diction. Here, he’s ideally balanced by King, whose attention to textural detail and rhythmic precision leave nothing to be desired.

Accordingly, the pair’s traversal of songs by Ralph Vaughan Williams, James Frederick Keel, Herbert Howells, Aaron Copland, Nikolai Medtner, and Robert Schumann brim with character and feeling.

Their take on Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel runs from a taut, swaggering account of “The Vagabond” and an austerely lyrical take on “Let Beauty Awake” to an effortlessly-phrased “Youth and Love” and a noble, hymn-like rendition of the album’s title track.

Keel’s Three Salt-Water Ballads offer a mix of puckishness and rhythmic intensity in the outer songs, “Port of Many Ships” and “Mother Carey,” while the central “Trade Winds” provides a floating respite.

The disc’s remaining numbers span Howells’ spiritual-like “King David,” Copland’s flawless setting of “At the River,” Steven Mark Kohn’s flowing arrangement of “Ten Thousand Miles Away,” Medtner’s “Wandrers Nachtlied,” and Schumann’s “Mondnacht.”

Suffice it to say, all are sung and played with a strong sense of shape and phrasing, as well as a compelling – but never pedantic – attention to the little musical details (of dynamic nuance and articulation, particularly). The result is an album that is thrillingly alive: a triumph from start to finish and one that lingers in the memory far longer than its fifty-minute duration.

Large-ensemble arrangements of chamber music rarely come off convincingly. And, truth be told, there are spots (mostly in the finale) in the 12 ensemble’s new album, Death and the Maiden, where the group’s adaptation of Franz Schubert’s eponymous string quartet simply needs to let the four section principals have at the music’s spastic sense of fun and contrast in order for it all to come alive.

Large-ensemble arrangements of chamber music rarely come off convincingly. And, truth be told, there are spots (mostly in the finale) in the 12 ensemble’s new album, Death and the Maiden, where the group’s adaptation of Franz Schubert’s eponymous string quartet simply needs to let the four section principals have at the music’s spastic sense of fun and contrast in order for it all to come alive.

But the larger performance works surprisingly well. There’s a flexibility to 12 ensemble’s performance that is ear-catching. The opening motive of the first movement surges. The five variations in the second inhabit their own, distinctive expressive spaces. The contrasts of character in the third are robust. And the finale, even if it lacks some of the spontaneity and freshness of the original, is limber and, usually, pretty snappy.

The remainder of the album’s repertoire likewise fares well. It’s all of more recent vintage.

John Tavener’s arrangement of his 1983 choral work The Lamb provides an inviting opener, its alternation of sparse verses with a warm refrain coming over strongly in the present performance.

Similarly catching is the lush, dreamy setting of Sigur Rós’ Fljótavík that closes the disc.

In between comes Oliver Leith’s Honey Siren, a three-movement study of the sound of sirens written in 2019. Abstract as the concept might sound, the piece itself fits beautifully with the Schubert (certain of Death and the Maiden’s first-movement chromatic shifts anticipate moments in Leith’s writing).

What’s more, it’s three movements are winningly varied. In the first, chilly tremolos and fragmented melodies gradually coalesce into a rich, chorale-like figure. The second features siren-like motives framing a sequence of radiant chords, while the finale explores wide oscillations of tone.

It’s beguiling music, a piece that doesn’t overstay its welcome, and one that’s kinetically-played to boot.

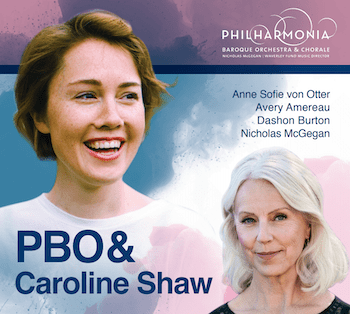

Two new pieces by Caroline Shaw are showcased on the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra’s latest release, both led by its music director Nicholas McGeegan.

Two new pieces by Caroline Shaw are showcased on the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra’s latest release, both led by its music director Nicholas McGeegan.

Is a Rose sets texts by Robert Burns, Jacob Polley, and Shaw. The Polley setting, “The Edge,” features touches of Minimalism as well as allusions to Handel (Shaw’s writing sometimes turns quite melismatic); additionally, it incorporates some fine solo oboe writing.

“And So,” Shaw’s meditation on Burns’ “Red, Red Rose” continues with Baroque allusions: there’s a prominent harpsichord part in addition to a vocal line that doesn’t lack for rhythmic interest. And her concluding setting of that Burns poem emphasizes the text’s reflective character, balancing episodes of rhythmic tension with familiar Shavian devices (hiccups, sudden pauses, the ensemble humming at the end – the last a very effective touch).

The whole piece is genial and ingratiating, if not quite so full of contrasts of texture, tempo, or mood as one might desire. That said, Anne Sofie von Otter proves a commanding soloist: her English diction immaculate, projection secure, and tone robust. McGeegan and the PBO provide vigorous accompaniments.

The latter do the same in The Listeners, an oratorio that pays tribute to the heavens and, in particular, the Voyager spacecraft. So do the soloists – contralto Avery Amereau and bass-baritone Dashon Burton – and the PBO Chorale, who imbue their respective parts with color and energy.

As in Is a Rose, Shaw’s writing is largely amiable: there’s an emotional directness to her musical language that is admirable and appealing. Additionally, she regularly demonstrates a strong sense of how to wrap up an individual movement.

And yet the limits of her style are more apparent in The Listeners than not. Text settings are sometimes awkward and stilted. Worse, music and words don’t often meet at the same level: indeed, an unaccompanied tape excerpt of Carl Sagan’s “lost lecture” proves more profound than any page of Shaw’s score. Ultimately, the piece is done in by a triteness of materials as well as a reliance on repetition over thoroughgoing musical development.

To be sure, The Listeners features some striking moments: the build of rhythmic intensity in “Of a million million,” the echoes of some of Shaw’s earlier successes (like Partita) in “Sail through this to that,” and the stately, noble “Epilogue” that ties everything up.

Even so, it’s hard to come away from The Listeners with the sense that it doesn’t lives up to its own aspirations or the equally lofty ones the album’s liner notes sets out for it.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.