Book Review: Superior Graphic Novels About Architecture

By Mark Favermann

What do graphic novels about architecture bring to our understanding of the urban experience? They suggest that buildings can be like our memories — they hide as much as they show.

An overhead view of Gotham City by Enrico Marini.

Over the last few decades, graphic novels have become an increasingly popular form of entertainment for adult readers. In the time of COVID-19, these “picture books” serve as particularly satisfying comfort food for our imaginations. Evolving from 1960’s alternative comics as well as decades of illustrated children’s books, graphic novels tell their stories through the use of chronological illustrations that come in a number of styles, from realistic, experimental, and fantastic formats to traditional comic book design. They can fit just about every genre: nonfiction as well as fiction, even thematically linked short stories.

Many graphic novels are illustrator or artist-driven, expressing a strong creative or personal perspective via a pictorial language that elbows aside the written word. For understandable reasons — the lure of the futuristic for the visual imagination — sci-fi and fantasy narratives predominate, often purveying a visionary or post-apocalyptic point of view.

When Art Spiegelman’s biographical-metaphorical vision of the Holocaust, Maus, received a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, the American public, including many literary critics, finally began to accept graphic novels as a serious art form. Spiegelman had not come out of nowhere; his effort built on personal graphic novels as well as genre-busting efforts coming out of the superhero world of Marvel and DC comics. Traditional bookstores now reserve shelves for feminist and LGBT graphic novels along with historical, science fiction, and fantasy entries. Pioneering graphic novels include the wonderfully subversive Love and Rockets series of the ’80s, Chicano-based stories penned by the talented brothers Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez. Another major series that deserves its high praise is Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. This work features poignant stories about the author/illustrator’s childhood and early adult years before, during, and after Iran’s Islamic Revolution.

I have always particularly enjoyed graphic novels that have served up an architectural or urban vision. Not surprisingly, they focus on a sense of place. Many of these works are dystopian in their graphic depiction of city life. Others are set in challenging utopian futures. The drawings run the stylistic gamut, from the eloquent to scratchy.

Among the many tomes that deal with the built environment, several stand out. There are the Batman books by various artist/illustrators (especially by the esteemed Italian comics artist Enrico Marini), a well-drawn Spanish language book about Mies van der Rohe entitled Mies, and the work of Ben Kantor in his weekly series for the Daily Forward, Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer. Some of Marini’s Gotham City depictions are as grand and awe-inspiring as renderings of the “urban heroic” by the celebrated Huge Ferris. In contrast, Kantor depicts the physical decay, municipal grittiness, and dense cultural/political resonances generated by the disconnection between those who build and those who use the built environment.

Three graphic novels about architecture are worthy of recommendation: Arterios Polyp; Robert Moses: The Master Builder; and The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade. Each book cleverly explores the highs and lows of architectural theory as well as urban planning and design. They also delve into the practice of the craft.

Asterios Polyp by David Mazzcchuelli. Pantheon Graphic Library, New York, 2009

Asterios Polyp is a middle-aged, meagerly successful paper architect (one who does not build anything) who often spouts theoretical gibberish. A professor, aesthete, and womanizer, the man’s rigid, self-absorbed lifestyle is upended after his Mid-Century Modern New York City apartment goes up in flames. Left in a thoughtless daze, he leaves his urban bubble and relocates to a small town in the American heartland, a place disconnected from his former reality.

Over the course of the book, Polyp’s character is developed as the narrative jumps back and forth between the past and present. Mazzcchuelli uses this boomeranging to do more than dissect social mores; he adds brilliant asides about a range of subjects, from design theory to human perception and man/woman relationships.

At its core, Asterios Polyp is an incisive study in self-destructive egotism. The arrogant protagonist pushes away Hana, a first generation Japanese-American artist whose love, theories, and desire for perfect architectural proportions offer an alternative to narcissism.

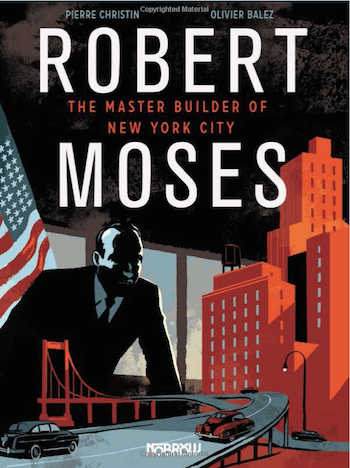

Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City by Pierre Christin (author) and Olivier Balez (illustrator), NoBrow, LTD., London, 2014

Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City by Pierre Christin (author) and Olivier Balez (illustrator), NoBrow, LTD., London, 2014

This nonfiction volume focuses on the life of the title’s powerful master builder and his controversial influence on everything from subways to skyscrapers, from Manhattan’s financial district to Long Island suburbs, from pools to playgrounds. Moses was responsible for much that is good and bad in New York City’s metropolitan transportation, infrastructure, housing, and parks. The graphic novel is an artistically successful look at a powerful man’s vision and his ability to implement it.

Less daunting than Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Power Broker and surprisingly informative, this volume brings a fresh perspective to the mega-planner’s trials and tribulations. It manages to capture his high energy and even finds a way to balance the former good versus evil notion set up by activist/writer Jane Jacobs’s crusade against him. This is an interesting yarn about a fascinating man presented well.

The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade by Viken Berberian (writer) and Yann Kebbi (artist), Fantagraphics Books, Inc., Seattle, 2019

One man’s blind ambition collides with authoritarian ideology and revolutionary zeal in a visually compelling graphic novel.

More in love with what he sees as the enthralling qualities of concrete than he is with his lovely girlfriend, Frunz yearns to become the next star architect. He’s a designer apple not falling far from its tree; Frunz’s father is known as Mr. Cement because of his love of austere brutalist structures. Dad is a builder who is wholly beholden to the reigning corrupt autocrats who run the city of Yerevan, the capital of post-Soviet Armenia.

A panel from The Structure is Rotten, Comrade.

Frunz and his father are socially and aesthetically disconnected from the country’s inhabitants, and they eagerly join up on a project to transform the city into a soulless mecca of high-rises. Irate citizens rise up against them and the city’s crooked regime. Everything in the man’s life eventually blows up; in the end, Frunz becomes a lowly draftsman of bathrooms in a dreary architectural practice in Paris. His anger and self-hatred are mitigated by his existence in the City of Lights. He will always have Paris. This tale of architectural defeat and slight redemption is drawn with passion, drama, and sarcasm.

What do graphic novels that revolve around architecture bring to our understanding of the urban experience? They suggest that buildings can be like our memories — they hide as much as they show. And that public structures can be expressions of our humanity — or its absence.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program. Since 2002, Mark has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

Schuiten’s Obscure Cities are an ode to architecture, in my humble opinion.