Book Review: “Play the Way You Feel” — Jazz on Film, Music and Myth

By Steve Provizer

Play the Way You Feel is the best volume around on the uneasy relationship between film and jazz.

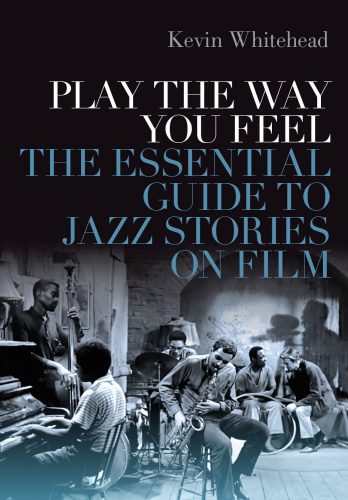

Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film by Kevin Whitehead. Oxford University Press, 400 pages, $34.95.

Author Kevin Whitehead, jazz critic for NPR’s Fresh Air, posits that film and jazz make use of parallel techniques: cross-cutting in film, call and response in big bands; the solo, the close-up. They also unspool in real time and draw on the mechanism of tension and release. Does this make them — as Whitehead claims — “natural allies”?

If they are, they are uneasy allies, as allies tend to be.

There are similarities in the technical language of both art forms. But major movie production is top-down, hierarchic, expensive, and script-bound. Jazz is rooted in community and can be produced at only the cost of a few instruments. Improvisation is at its center. A jazz musician’s life may be colorful enough to inspire the production of a film, but few lives fall neatly into Hollywood’s standard three-act screenplay format. Inevitably, there must be some excruciating shoehorning. The complications of la vie du jazz are always subservient to the needs of plot, and that means the credulity of the jazz lover, who knows much of the back-story, is stretched to the breaking point.

What makes analyzing the relationship between film and jazz interesting is the constant but uneasy negotiation between the two art forms. Though I find these two “allies” more at odds than Whitehead does, it doesn’t undercut the undeniable value of his book. This is the best volume around on how the film-jazz scenario plays out. Most such books on the subject are either a gathering of hundreds of short précis/reviews or academically oriented tomes that try to prove the author’s thesis through pedantic analysis of a small number of films chosen to buttress his or her argument. (Consumer alert: check for Adorno and Freud in the index). I applaud the fact that Whitehead takes a third approach. He has chosen a representative sample of films with substantial jazz elements and gives the reader clearly written, detailed explanations of the plots of these (65) films. He also treats about the same number of films in a briefer manner.

Each extended film reconstruction reflects Whitehead’s careful watching and thorough research. He approaches each movie by applying what he sees as its principal jazz trope. The book’s title, Play the Way You Feel, alludes to one of those motifs, and it is probably a key theme: playing jazz represents the apotheosis of personal freedom and expression. The most frequent obstacle in a jazz film for a protagonist is that someone, some organization or some other malevolent presence tries to keep the protagonist from pursuing his (always a man) vision of “real,” “true,” or “pure” jazz. Whitehead then explores how this plot structure — the creative artist challenged — plays out in a given film.

He’s a keen observer. Whitehead catches how a member of the sax section moves mysteriously from one side of the band to the other between consecutive shots; he notices how Art Tatum’s piano is muted in The Fabulous Dorseys when it comes time for Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey to solo. I was happy to learn details about which musicians were “ghosting” on the soundtracks (performing on the instrument we see an actor play on-screen), including Harry James for Kirk Douglas in Young Man with a Horn, Nat Adderley for Sammy Davis in A Man Called Adam, Snooky Young for Jack Carson in Blues in the Night, and Bunny Berigan ghosting for Rex Stewart (!) in Syncopation. Other interesting facts are revealed about the 1947 film New Orleans. For about 15 years, Louis Armstrong had been performing as a soloist backed by a big band. He was cast in New Orleans to play with a small group. As a tie-in with the release of the movie, his manager Joe Glaser booked him with a similar sized group, which evolved into the “Louis Armstrong All-Stars,” the band that he traveled with (with personnel changes) for the rest of his career.

A scene from Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life.

There are times when Whitehead’s lengthy descriptions seem somewhat gratuitous. It’s illuminating to evaluate jazz musicians when they’re actually called upon to act (rare, but it happens). But do we need to know this detail about drummer Gene Krupa in George White’s Scandals (1945): “When a bevy of beauties sign up to audition for producer White’s girly show, Gene and his men eavesdrop to write down phone numbers: Krupa writes them on a drumhead.” Well, okay…

Other descriptions, while not exactly on point, provide canny background color: Writing about a scene in Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life, its music provided by Duke Ellington, Whitehead notes, “Now as the music continues, the scene shifts again, to industrial-age laboring in rhythm: Olive-skinned men in short sleeves or stripped to the waist (but wearing snakeskin boots or loafers).”

Whitehead credits academic Krin Gabbard’s work on jazz and film, referring to him several times. He generally agrees and occasionally disagrees with his cinematic analyses. I’m not an admirer of Gabbard’s — he has a tendency to stretch the facts to fit his theses. As I argue here, Gabbard seems to envision “people [in film] being moved around by The Man as if on some giant pathological chess board…. citing only one or two examples per decade fuels the thought that the theory came first and that evidence was chosen to support it.” Thankfully, Whitehead is level-headed and independent when it counts — his extrapolations all seem well founded.

Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong in New Orleans.

Whitehead’s major fault is not giving enough attention to the issue of how cinema dealt with — or refused to deal with — the question of mixed race bands on screen. It does sometimes arise here, but it was a problematic issue from when jazz first hit the big screen in the ’20s. The sad story of how musicians had to have their skin lightened or darkened — or were made to perform hidden behind scrims — is one that should be more completely investigated and told.

As is to be expected, not everyone will agree with Whitehead’s choices and evaluations. I think Sean Penn does a better job of simulating guitar playing than Whitehead does in Sweet and Lowdown. Sweet Smell of Success deserves more attention than Whitehead gives it. Whitehead can be glib on occasion, as when he notes that Billie Holiday looks great in the film New Orleans because “she knew who to befriend on the set — the cameramen.” In truth, she’d have had to befriend the Director of Photography — the one who’s really in control.

But these are minor quibbles. I follow this film-jazz relationship pretty closely and I’m happy to see this book. Whitehead takes a glass-half-full attitude; he believes that all of the films he covers get at least something right. Maybe he’s setting up jazz lovers for more falls; or it could be he wants us to bring a different set of expectations. We should reconcile ourselves to the exigencies of the cinema and let go of the hope that the emotional rewards of jazz can be dramatized in feature films. As for me, I can only set the bar so low if a movie purports to portray the life of a specific musician. Overall, I’m willing to accept these films as they come: as projections of the mythologies popular culture has spun around the art of jazz and its practitioners. Whitehead’s Play the Way You Feel is a very useful guide to the cinematic web.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subject, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

It’s NPR remember!

You refer to the “glass half full attitude”? Yes.

Wow! I’ve just been rediscovering jazz musicians and the films/movies/documentaries that I was exposed to during my undergrad studies at University of Victoria (BFA Visual Arts/Film Studies minor 2000) and how did we miss Sister Rosetta Tharpe during our classes? Because black women musicians like Hazel Scott didn’t have the same level of fame unless their lives were somewhat notorious or negatively impacted by addictions or mental health. Having the maturity and ability to appreciate music’s impact on our lives blessed me with the choice to make film studies and music my minor. I used the knowledge I gained to carry forward into my Master’s studies in Animation and Arts Education to develop curriculum to further my study and research goals. I only heard a short clip of the review on KNKX this afternoon so am glad you have the review here!