Visual Arts Feature: Artists Respond to the COVID-19 Crisis in Prisons

By Patrick Conway

Much of what artists and educators who enter prisons typically aim to do is help foster human connections with those on the inside.

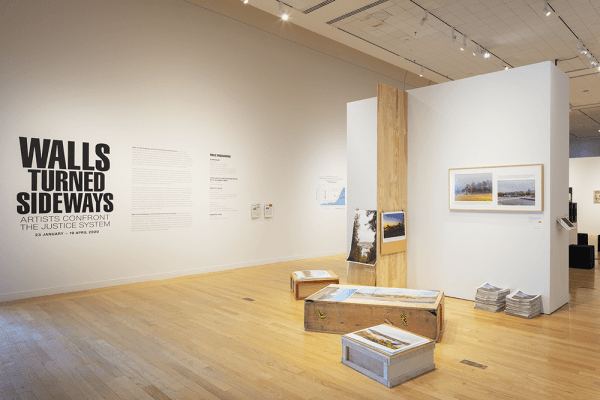

A part of the closed exhibit Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System.

If there is any doubt about the threat the COVID-19 pandemic poses to incarcerated populations, a quick check of the highest per-capita cases by county throughout the country should wipe it away. The small county of Marion, OH, ranks right near the top of the list, in large part due to a massive outbreak at its state prison. As of April 27th, nearly 80 percent of prisoners housed at the Marion Correctional Institution have tested positive for the virus, representing nearly 1,950 cases. Elsewhere, the situation is not much better. The Wall Street Journal reports that more than two thirds of the small number of federal prisoners who have received COVID-19 tests have returned back positive results, suggesting that the situation is much more dire than the data we have at the moment shows.

This past Wednesday night, artists, educators, and activists from around the country gathered virtually to discuss ongoing campaigns for prisoner release in response to the pandemic. In the conversation hosted by Tufts University Art Galleries (TUAG), curator Risa Puleo and artists Sarah Ross and Damon Locks reflected on the role artists can play in responding to the risks that COVID-19 poses to incarcerated populations. Puleo is curator of the exhibit Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System, which was presented at the Tisch and Koppelman Galleries in Medford before the show was forced to close on March 12th due to the pandemic. Ross and Locks, whose work is included in the exhibit, have a long history of teaching behind bars with the Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project (PNAP), a grassroots organization that offers arts and humanities classes at Stateville Prison outside of Chicago.

The evening’s discussion largely centered around detailing the many dangers that prisoners now face as a result of the virus. From inadequate health care operations and overcrowded facilities to the near impossibility of implementing sufficient social distancing measures, the conditions inside most prisons are ripe for a quick and deadly spread of the virus. Even within facilities where no known cases yet exist, anxieties pervade. The response by many prisons, as reported by the Marshall Project, has been to initiate prison-wide lockdowns, confining prisoners to their cells and bunks until further notice. As of April 15th, well over 300,000 prisoners nationwide faced such restrictions. That number, of course, is only likely to grow.

One of the major challenges for artists and activists is that each state is responsible for managing its own prison system, which means there is little consistency regarding remediation. In some states, officials have decided to either furlough or release a certain percentage of prisoners. But even then, as Ross and Locks both pointed out, the determination of who gets to be let out becomes murky. Often, the decision is based on whether a prisoner’s offense was violent or nonviolent. But, given that the virus poses a greater risk for the elderly, that may not always be a suitable strategy. The demographics of those incarcerated for violent offenses tends to skew older; they are likelier the ones who serve longer sentences and are less likely to be paroled. Of course, in many cases, these men and women are far different from who they were at the time of their offense. They are unlikely to pose a threat to the communities to which they would return.

Part of the difficulty for states and the federal government in addressing the needs of incarcerated people during the spread of the virus is this is really two crises rolled into one: the dangers associated with COVID-19 lumped on top of the preexisting crisis of mass incarceration, which the original art exhibit explored. With nearly 2.3 million Americans incarcerated, the criminal justice system is anything but equitable. Black communities are disproportionately impacted; they represent roughly 13 percent of the total population but make up nearly 40 percent of the prison population. Rates of incarceration and poverty have also been shown to be very closely correlated. Beyond the human cost, the economic burden of this predicament is enormous. Recent research suggests the overall cost of mass incarceration might be as high as nearly $1 trillion per year — if you include the money spent by individuals, families, and communities.

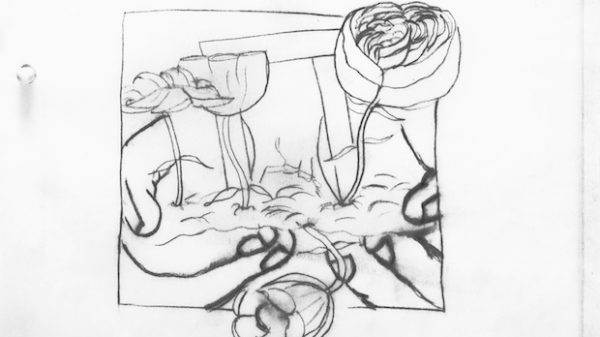

Much of what artists and educators who enter prisons typically aim to do is help foster human connections with those on the inside. But, now that the pandemic has effectively barred outsiders from entering prisons, artists like Ross and Locks have been forced to reassess their own capacity to assist. Their efforts are now mainly directed toward spreading awareness of the imminent harm prisoners face, their heightened risk for contagion and possible death as a result of COVID-19. Part of their plan for raising such awareness is by using art to amplify the voices and experiences of those who are incarcerated, such as in Locks’s animated short film Freedom/Time, which includes the works of 11 different incarcerated artists who were each asked to draw 100 frames for the project.

A still from Damon Locks’s short animated film Freedom/Time.

While the current standing of prisoners remains perilous, there is some cause for hope. Just this past week, a federal class action lawsuit was filed to protect men and women incarcerated at a federal facility in Danbury, Connecticut. Citing “unlawful and unconstitutional confinement,” the suit’s petitioners seek an emergency order to transfer the most medically vulnerable to home confinement as well as to begin implementation of social distancing measures to limit the virus’s spread. Prisoners’ rights activists are hopeful that a favorable decision could potentially generate a ripple effect in terms of expectations for care. Such steps are a sign of progress, but the American legal system can be painfully slow. In the interim, prisoners remain at risk.

Artists like Ross and Locks are being compelled by a sense of urgency to increase involvement in relief efforts. Beyond spreading awareness to help galvanize support, the two have been building relationships as part of nationwide organizing efforts to secure bare essentials — such as soaps, sanitizers, and masks — for use in prisons. The American justice system has demonstrated an immense capacity to punish and incarcerate, but it has shown nowhere near the same capacity to provide adequate care.

Patrick Conway is a former criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, DC, and Boston, and a current doctoral student at Boston College researching the implementation and expansion of higher education programs in prison. His writing has appeared in literary and education journals, and has received recognition from the Best American Essays anthology.