Book Review: “Shakespeare in a Divided America” — Illuminating the Bard’s Influence on Our History

By Steve Provizer

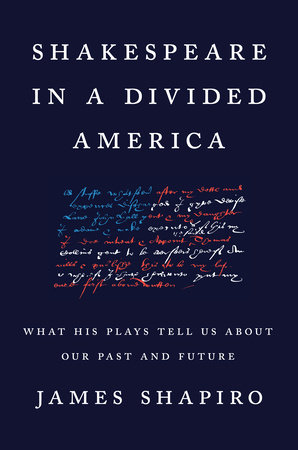

Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Our Future by James Shapiro. Penguin Press, 320 pages, $27.

Shakespeare’s role in American history is not immediately apparent — at least it wasn’t to me. Part of the considerable pleasure of reading this book is seeing how James Shapiro draws the connections.

“Shakespearean” is America’s fallback adjective for archetypal dramatic scenarios. No other literary or artistic name or body of work carries nearly the same power. Many of us can quote snatches from a few of his most celebrated speeches: To be or not to be; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him; Life’s but a walking shadow. Even after decades of aggressive reevaluation of literature by “dead white males,” Shakespeare’s stock as a cultural touchstone remains high. Some literary men are deader than others.

Still, it comes as a shock to learn the degree to which Shakespeare’s plays have played a vital part in some key turning points in U.S. history. As author James Shapiro very effectively explores in Shakespeare in a Divided America, important players on both sides of our country’s most contentious issues have understood the appeal of the Bard and have used his work as a way to try to exert influence at crucial political and cultural junctures.

Shapiro structures his argument through a series of chapters: 1833: Miscegenation; 1845: Manifest Destiny 1849; Class Warfare, 1865; Assassination, 1916; Immigration, 1948; Marriage, 1998; Adultery and Same-Sex Love; and Conclusion 2017: Left / Right. Each focuses on a specific happening or a series of events. 1833 focuses on John Quincy Adams and the actress Fanny Kemble; 1845 deals with the war with Mexico; 1849, the burning of the Astor Place Opera House and New York City riots; 1865 takes up Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth; 1916 is about restricting immigration; 1948 explores the making of the musical Kiss Me Kate; 1998 examines the production history of the film Shakespeare in Love; and 2017 deals with the controversy generated by a production of Julius Caesar mounted by New York City’s Shakespeare in the Park. Shakespeare’s role in most of these events is not immediately apparent — at least it wasn’t to me. Part of the considerable pleasure of reading this book is seeing how Shapiro draws the connections. A couple of chapters will serve as examples.

1833: Miscegenation takes a close look at John Quincy Adams’s views on slavery and shows how ingrained racism was in Boston. It turns out that while Adams was known for being antislavery (he defended slaves in the Amistad case), he was dead set against miscegenation. He expressed his distaste though his dismissal of Desdemona in Othello. He found her desire to have a sexual relationship with a black man disgusting and abhorrent. He felt that she deserved her painful death. He wrote several times on the subject and came into conflict with the British Shakespearean actress Fanny Kemble, whose racial views and feminist perspective were far more enlightened. Her Desdemona, as she put it, was determined to make “a desperate fight of it” in the “smothering scene” rather than “acquiesce with wonderful equanimity.”

Othello is once again at issue in 1845: Manifest Destiny. The action here unfolds in an army camp on the Mexican border, as the U.S. is on the verge of initiating the Mexican-American War, a product of our country’s embrace of Manifest Destiny. The debate on the question of “destiny” was linked to a conflict of ideas about what constituted masculinity. Shapiro explains: “A restrained masculinity that embraced moderation, virtue, domesticity, and sobriety … was being elbowed out by a more martial manhood, one characterized by a greater tolerance for excess, alcohol, physicality, and domination.” And, in one of his many comments that resonate today, Shapiro adds, “This model had a special appeal for workingmen who felt left behind in an age of rapid economic transformation.”

Two Shakespearean elements prove to be relevant. In one, a staging of Othello is planned for an army encampment along the Mexican border. Ulysses S. Grant, future Civil War general and president, was tapped to play the role of Desdemona. A contemporary description of Grant suggests why: “Young Grant had a girl’s primness of manner and modesty of conduct. There was a broad streak of the feminine in his personality. He was almost half-woman, but the strand was buried in the depths of his soul.” Given the contention over what defined manhood, the ambiguity of having a man undertake the role was too much. Grant did not play Desdemona: a woman was brought in to do the role. (After this incident, Grant decided to grow a beard.)

At the same time, the question of masculinity was raising its head elsewhere, in productions of Romeo and Juliet. And more than the definition of masculinity was in play — so was nationalism. On one side, there was the British actor William Macready, who practiced a relatively restrained, naturalistic acting style. On the other, there was the American actor Edwin Forrest. As Shapiro explains: “Forrest came to represent qualities of Jacksonian democracy… that came to be identified with the nation’s seventh president: anti-elitist, racist, manly, expansionist, nationalist, in favor of limited regulation and a more powerful presidency and mostly good for white men.“ Again, one asks — sound familiar? There is a political backdrop for the theatrical fracas; driven by his belief in Manifest Destiny, President Polk broke the sharing agreement the U.S. had with Britain, claiming the entire Northwest for America.

If my description of the 1845: Manifest Destiny chapter sounds interesting, it is no more so than what follows. Shakespearean productions in the U.S. were not just flash points for our understanding of masculinity and nationalism; they probed class differences as well. Time and again, Shakespeare’s work takes up issues that America has never fully resolved — racism, sexism, infidelity, marriage, xenophobia, and unequal wealth distribution.

I have few complaints to raise about this study, though Shapiro’s extended description of how the Right Wing utilized new and old media to raise hell about a production of Julius Caesar is a little overdrawn and outside of his argument’s scope. The author writes that “[Director] Eustis had wanted a dialogue, even a heated one, while those offended by his memorable production opted for silencing him and his theater company. His production, however inadvertently, had shown how easily democratic norms could crumble.” In truth, the book demonstrates that these are democratic aspirations, not norms.

Shapiro notes Shakespeare’s expanded presence in America’s Common Core curriculum, but he goes on to write that “there has always been a tug-of-war over Shakespeare in America; what happened at the Delacorte [Central Park theatre] suggests that this rope is now frayed.” Shakespeare in a Divided America ends with a warning flourish, citing how in 1642 the English Parliament, at the beginning of the Civil War, declared that “public stage-plays shall cease.” The closing of London’s theaters followed.

I’m not confident of the continued health of theater in America, or the arts in general, especially in the era of COVID-19. Things will be different once we are on the other side of this pandemic. Yes, Shakespeare was important in our history, but there is more at work here. Shapiro observes that Trump is the first of our presidents who seems to have no interest at all in Shakespeare. That is not a good cultural sign or symbol, but it’s the least of what worries me about him. After all, throughout our history aficionados of Shakespeare have used his work to defend slavery, manifest destiny, and nativism, and have vaunted the superiority of the “Anglo-Saxon” race. If Trump found this out, he might start reading — or probably watching — Shakespeare. I’m not sure this would be a good idea.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subject, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Thank you very much. I will search for the book in Israel.