Arts Remembrance: Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020) and Christopher Rouse (1949-2019)

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Many of the qualities that mark Penderecki’s best work – exquisite technique, an innate feel for rhythmic athleticism, an ear for dazzling colors and theatrical gestures, an impeccable sense of musical structure, and the affinity for emotional immediacy – are also hallmarks of Rouse’s.

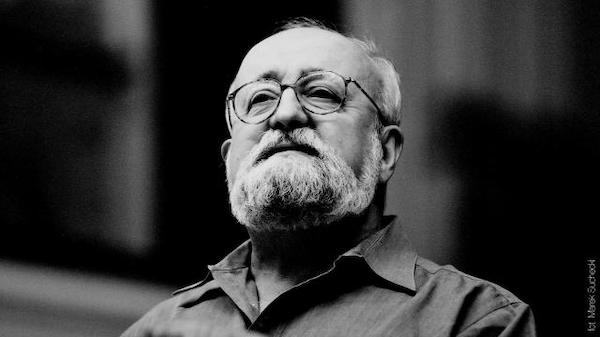

The late Krzysztof Penderecki — his compositions married cutting-edge technical and harmonic concepts of the 1950s and ’60s with a striking feel for expressive directness.

Krzysztof Penderecki, who died after a long illness on March 29 at 86, was one of the rarest of composers: a prominent voice of the post-World War II avant-garde who gained a devoted – and diverse – following that stretched far outside the narrow bounds of contemporary classical music.

He managed that by writing music that married cutting-edge technical and harmonic concepts of the 1950s and ’60s with a striking feel for expressive directness. Thus, pieces like Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (1960) and Polymorphia (1961) proved more than mere sonic experiments: in his music, Penderecki’s use of tone clusters, graphic notation, microtones, and the like were infused with a breathtaking emotional immediacy. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, both of those pieces – and several others of Penderecki’s – have figured in the soundtracks of films by William Friedkin, Stanley Kubrick, and Martin Scorsese, among others).

Even as some of Penderecki’s music was downright radical, much of it was built on an essentially traditional foundation. His approach to form tended to be straightforward (Polymorphia, for instance, is laid out in, basically, an A-B-A structure). Nor did he eschew canonic genres: Penderecki’s catalogue boasts eight symphonies, four operas, and no fewer than two dozen concertante works, alongside many chamber pieces. And, in his extensive body of sacred works, one can draw a direct line back to the choral pillars of Bach and Handel.

While Penderecki’s most notorious pieces date from the 1960s, in the following decade he underwent a stylistic conversion, of sorts. Beginning with the 1979-80 Symphony no. 2 (subtitled “Christmas Symphony” for its subtle quotations of the carol “Silent Night”), he began to adopt a language that was increasingly tonal and neo-Romantic.

Astringent dissonance and inventive instrumental combinations were still present, but they formed a more discreet part of Penderecki’s toolkit. In general, the music of his last four decades took on a more conventional (as well as highly polyphonic) hue.

To these ears, some of those efforts (like the 1997 Violin Concerto no. 2 he wrote for Anne-Sophie Mutter or the 1989 Symphony no. 4) meander, lacking the direction and intensity of his best early-period works. At the same time, they reveal a composer of music often shaded by tragedy, brilliant technique, and keen expressive sensibilities (that Fourth Symphony took home the 1992 Grawemeyer Award).

To be sure, the best of his second-period output – like 1996’s “Seven Gates of Jerusalem” and the magnificent 2008 Horn Concerto, Winterreise – beguile the ear with their sheer sense of invention, play of colors, and thrilling virtuosity.

Locally, Penderecki’s music has appeared occasionally on Boston Symphony Orchestra programs, most recently at Symphony Hall in 2013 when Charles Dutoit led his Concerto Grosso for Three Celli and Orchestra. The piece was standard-issue tonal Penderecki – full of striking ideas, running a bit longer than necessary – and fervently played. On that occasion, I found myself seated across the aisle from the great man and he obliged me with an autograph at intermission: it was a fleeting brush with one of the last century’s few truly iconic composers, one who now belongs to the ages.

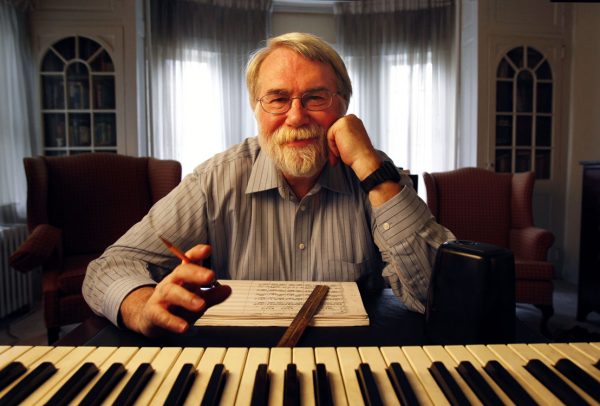

The late composer Christopher Rouse — his was a body of work that was haunted by death. Photo: Gramophone.

Penderecki wasn’t the only major composer we’ve lost of late: Christopher Rouse, one of the giants of the American symphonic scene died on September 21 after a years-long battle with renal cancer.

Like Penderecki, he was a stocky, bearded guy, one whose music could generate mega-decibels. Rouse labeled rock music and Stravinsky as two of his formative influences and the visceral, pummeling thrills of both were never far removed from his, be that in the hellish finale of Phantasmata, throughout the piano concerto Seeing and the percussion-orchestra “fantasy” Der gerettete Alberich, or in his ferocious Symphony no. 3.

At the same time, Rouse’s music could be tenderly introspective – the outer movements of his 1993 Flute Concerto are among the most exquisite in the repertoire – and winningly characterful (as in the flamenco-tinged guitar concerto Concert de Gaudí of 1999 or the frolicsome 2005 ballet Friandises).

Often enough, his was a body of work that was haunted by death. Rouse’s Symphony no. 1 is a searing Adagio with more than a few nods to Shostakovich at his bleakest. His Symphony no. 2 is a memorial to the composer Stephen Albert. The Pulitzer Prize–winning Trombone Concerto of 1991 was written as a tribute to Leonard Bernstein, and the Flute Concerto is dedicated to the memory of the murdered English toddler James Bulger.

While his prolific output took a decided turn “towards the light” (as the composer once put it) starting in the 1990s – the chorus-and-orchestra holiday score Karolju, the chamber-sized Compline, and curtain-raiser Rapture shimmer – it never completely left the shadows behind. His tenure as composer-in-residence for the New York Philharmonic in the early 2010s, for instance, yielded, alongside the lighthearted Thunderstuck, a dark trilogy: the harrowing Odna zhizn, murky Prospero’s Rooms (after Poe), and the devastating Symphony no. 4.

Even so, many of the qualities that mark Penderecki’s best work – exquisite technique, an innate feel for rhythmic athleticism, an ear for dazzling colors and theatrical gestures, an impeccable sense of musical structure, and the affinity for emotional immediacy – are also hallmarks of Rouse’s.

All are on display in the valedictory Symphony no. 6 that received its premiere in Cincinnati last October, mere weeks after the composer’s death. A recording of the debut performance recently appeared on YouTube and it reveals one of the most touching symphonic farewells in the canon.

Rouse evidently intended the Symphony as his final statement, and echoes (though no direct quotes) of Mahler’s haunting Ninth Symphony pop up here and there. Its two quick central movements provide moments of contrast, if not exactly relief, from the intensities of the outer pair.

Those last are highlighted by the appearance of a doleful flügelhorn, whose lamenting subject serves as the thematic anchor for the larger work. Indeed, the finale is a passacaglia whose variations work their way back to it: after a surging climax and a strangely comforting hymn for strings in E major, the flügelhorn motif returns and the music unwinds, gently but inexorably, until it’s suddenly cut off. Beneath the double-bar in the score, the composer penned a single word, “FINIS.”

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.