Book Review: “Franci’s War” — A Very Relevant Holocaust Memoir

By Roberta Silman

Here is a young Czech woman who could not only take a piece of fabric and shape it into a gorgeous dress, but who could also take her experiences during the Second World War and shape them into a compelling memoir, a work of art.

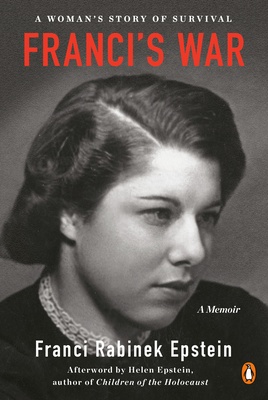

Franci’s War, A Woman’s Story of Survival by Franci Rabinek Epstein, Penguin, 256 pages, $17

Sometimes it is necessary to start with a book’s provenance. This memoir, originally called Roundtrip, was finished in 1975 and submitted to editors all over New York City, to no avail. By then its author was 55, had survived the Second World War, had lost her parents to the Nazis, and had emigrated to the United States with her second husband. She was the owner of a successful high-end salon on the Upper West Side and the mother of three children, the oldest being Helen Epstein, our Helen, a Senior Contributor to The Arts Fuse and author of the well-known Children of the Holocaust and several other books.

According to Helen’s Afterword, her father wanted to leave Prague as soon as the Communists took control in January 1948, seeing them as “Nazis in different color uniforms.” Her mother resisted; she had survived the concentration camps and, miraculously, she had returned to her beloved Prague, where she had recreated her own fashionable salon and had given birth to a daughter, then an infant. Then Jan Masaryk was brutally killed in March. As Helen tells it,

My parents flew out of Prague on July 21, 1948, with two suitcases and me in a canvas bag. Franci wore all the clothing she could. Along with diapers, she packed the Epstein and Rabinek family photographs and three porcelain figurines that had belonged to her mother.

In that same Afterword Helen quotes her mother’s preface to the original memoir, which Franci called “Explanation.”

Why do I feel compelled to add my voice to the great chorus of statistics, learned reports, psychological studies as well as more or less successful treatments in fiction and drama already written? There is no one answer, but perhaps my first and foremost concern is with my children and their generation, who seem to me almost as troubled as I was at their age. They are prone to deep exasperation about the status quo, and to flight into drugs. . . .

Since children tend to be strangers to the inner life of their parents and their motivations and reactions, and having no fortune to bequest, I can only try to give them an honest and true picture of their mother in her youth and of my way of dealing with the perplexities of existence. It might give them some understanding of the diversity and often puzzling behavior of the human animal, in addition to the dreadful corrupting force of power in the hands of a few individuals, who usurped it with the help of an indifferent, intimidated, and dissatisfied population.

That gives you a taste of what Franci was like — brilliant, wry, amazingly self-aware, and interesting. And why this memoir is so valuable, for here we have the story of a young Czech woman who could not only take a piece of fabric and shape it into a gorgeous dress, but who could also take her experiences during the Second World War and shape them into a compelling memoir, a work of art that is, not at all incidentally, totally relevant in 2020, the 75th anniversary of her liberation from the camps.

Franci Rabinek was born in 1920, two years after Czechoslovakia was created from former lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire known as Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia. Her parents, Emil and Pepi, were Viennese Jews who had come to Prague and chose to convert to Catholicism, but when Franci, an only child, was 13, she preferred to be identified on her papers as “without religious affiliation.” She was thoroughly assimilated until Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939 and the Racial Laws prevailed. Franci’s four Jewish grandparents stamped her as a Jew. By then she was 19, the owner of her mother’s haute couture (literally high-end sewing) business in Prague — why, is never made entirely clear — and “interested in dancing, my business, flirting, and skiing, in that order.”

By June of 1939 she and her parents were arrested by the Gestapo, who were actually looking for Joe Solar, Franci’s boyfriend, a member of the Resistance whose contacts had led them to a list of jewelry belonging to Pepi. A bribe was delivered, and they were released. First to get home, Franci also discovered in her father’s desk a vial of pills, which would play a part as the story evolved.

Against her father’s wishes, but with the blessing of her mother, who knew she was more than a little wild, Franci married Joe Solar in August of 1940. Six weeks later she discovered she was pregnant. Wise enough to know that she and Joe were hardly able to take care of a Jewish child, she had an abortion. After that their life became a bit less hectic; by now the four of them were living together in a small apartment on the outskirts of the city, and although Franci still worked in the salon she had handed over its reins to her gentile assistant, Marie.

Helen Epstein, an Arts Fuse contributor and author of the well-known Children of the Holocaust and several other books.

Everything changed after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in the spring of 1942. In reprisal, the Nazis destroyed the town of Lidice, and Jews were being transported from Prague. At first, young men like Joe were needed to build the railroad to Terezin. Then families. As crazy as it sounds, Franci was scheduled to have her tonsils out during this very time. The operation was performed but was more complicated than anticipated. Because of that she was exempt from the transport, but she refused to let her parents go alone, checked herself out of the hospital, and two days later they, too, were in Terezin.

Almost immediately it became clear that her parents were headed for another concentration camp. At this point her father patted the little vial of pills in his pocket, saying he would never die at the hands of the Nazis. Then Franci confessed that she had gone to a pharmacist and substituted saccharine for the original pills, thus robbing her father of escape. Franci tried to go with her parents, but the Nazis refused. Her father left in a rage, her mother was calm. She gave Franci her blessing, saying, “You are very young and your only duty to us is to stay alive. Your life is before you.”

Franci never saw her parents again.

The rest of this precise and even-handed, yet often harrowing memoir describes Franci going from Terezin to Auschwitz-Birkenau, to the slave labor camps at Hamburg, and finally to Bergen-Belsen, where she was liberated by the British. Sophisticated beyond her years, extremely alert to all kinds of vibes, and quick on her feet, Franci passes herself off as an electrician — more necessary than a seamstress — and writes frankly about the hunger and filth and brutality as well as sex in all its variations, especially its use as barter among people desperate to survive. Although she is capable of making close relationships, she also discovers a personal method of survival that many of us have experienced in flashes in our ordinary lives but which sustained her for years in captivity. Berated by her cousin Kitty for not trying to escape soon after coming to Auschwitz, where Kitty is sure they will be cremated, Franci describes what happened:

A very strange sensation took hold of me then. I stared down at my tattooed arm, and like a badly focused picture in a camera, it slowly detached itself and became two arms. But only one had a tattoo. I tried to focus back, but the movement continued until there were two of us: me and A-4116. I thought, What is she doing here, poor devil? I know her. I’m sorry for her, I’ll watch her. She looks just like me.

Somehow A-4116 maneuvers her way through all the challenges with both her wits and her sense of humor intact. Here she is in Neugraben outside of Hamburg, told by her boss Spiess that he wants a telephone moved:

Gingerly she unscrewed the wall box and made a diagram of exactly how the wires were connected, using colored pencils from his desk. Then she removed the box, connected the new cable, isolated it, and drew it along the corridor. She tacked it to the wall, praying to the patron saint of electricians to make the damned thing work. When she got to the other end of the barrack, she remounted the box, connected the telephone, and picked up the receiver in a cold sweat. A dial tone sounded just as Spiess returned to see how far the work had progressed.

From that moment on, Spiess developed the ridiculous idea that she could do almost anything.

Her ability to distance herself clearly helps, and only after she recovers from typhus, so prevalent in Bergen-Belsen after liberation, does she become Franci again, a young widow back in her cherished birthplace. Yet she is still restless and conflicted. As she says, “I wanted very much to be the independent, self-sufficient, free woman. Yet I kept casting around for a fatherlike figure to keep me from foolish escapades, often not trusting my own judgment.” She finally achieves some peace on New Year’s Day, 1946.

The sky was cloudless and the pine trees were heavily figured with new snow. There was not a soul around to take away the sudden intimacy between myself and the universe. Awed, I looked at the miraculous beauty surrounding me . . . If there was a God, I felt his presence here, as well as gratitude for being alive. I buckled on my skis, and whistling the last movement of my favorite Brahms symphony, I schussed down the hill.

For the details of Franci’s life henceforth, we have the wonderful photos and the Afterword by her daughter, which tell us about Franci’s second marriage and her complicated life in New York, where she raised three children and ran another fashion salon. Sadly, this remarkable woman died of an aneurysm in 1989 when she was only 69. But proof of her generosity of spirit and great intelligence is here in the last part of that important “Explanation,” after an American doctor asks her if she hates the Germans.

I do not, mainly because I feel that hate is a sentiment I can ill afford, since it ultimately leads to the hatred of oneself. . . .

But she is human, after all, and she has, understandably, resentments: former Nazis whitewashing themselves, the tacit approval of much of the population during the war, the meager rehabilitation payments, etc. However, it is her last words that are most important and most relevant at this very moment in our own country:

All this, though, does not add up to hate—more to a curiosity whether there, in fact, exists a new Germany. Could this new Germany withstand another mass hysteria to “Follow the Fuhrer” if another madman arose in another disastrous economic depression, with a need for a scapegoat?

My greatest concern is the possibility that due to human nature, it could happen again in a different form, under different circumstances, anywhere in the world.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: A Woman’s Story of Survival, Franci Rabinek Epstein, Franci’s War, Helen Epstein, Holocaust