Book Review: The ‘Papa’ of Male Modern Dance, Ted Shawn — A Story of Changing Norms

By Debra Cash

In this new biography, Ted Shawn is on display in all his narcissism, paternalism, hypocrisy, originality, and the dedication to creative expression that set American modern dance on its way.

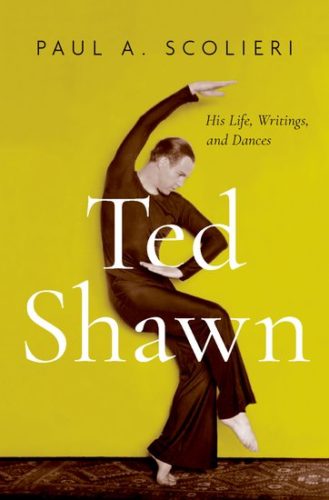

Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances by Paul A. Scolieri, Oxford University Press, 2019, 552 pages, $39.95

All art tells an inherent story about the times in which it was created, but that story is not always identical to the story that the artists claim to tell about their own intentions. The hindsight that Paul Scolieri brings to his telling of the life and art of Ted Shawn (1891-1972), the “papa” of male modern dance in the United States, is a story that Shawn himself resisted telling.

All art tells an inherent story about the times in which it was created, but that story is not always identical to the story that the artists claim to tell about their own intentions. The hindsight that Paul Scolieri brings to his telling of the life and art of Ted Shawn (1891-1972), the “papa” of male modern dance in the United States, is a story that Shawn himself resisted telling.

Ted Shawn’s homosexuality — an open secret throughout his never-legally-ended heterosexual marriage to dancer Ruth St. Denis, hidden from the scrutiny of the media long past when it would have mattered — constrained and shaped American ideas about male concert dance. His is a story about how a Midwestern Methodist who planned to be a minister until a bout of diphtheria at age 19 led him to dance as physical therapy sought refuge in both Christian Science and a notion of “muscular Christianity,” designed to offset the “emasculating effects of modern living.” Shawn’s hyperbolic and kitschy orientalism, something that was already in place in his wife’s vaudeville enactments of priestesses and goddesses by the time he met her, now reads as colonial entitlement. His life and work limn the push and pull between “high art” — that which spoke to important humanistic values — and commercial entertainment. The company of men he gathered and mentored (and sometimes bedded) on a rural compound called Jacob’s Pillow from 1933 to 1939 hints at the particular challenges of building an arts institution in the United States in the 20th century and beyond. Ted Shawn’s life is ultimately a story of changing norms. As one Los Angeles critic remarked in 1916 after seeing the Denishawn School of Dancing’s clearly over the top A Dance Pageant of Egypt, Greece and India (or The Life and After-life of Greece, India and Egypt), “If women are going to vote, why under the sun should men not dance?”

Scolieri draws his material from a wealth of resources, many previously unpublished. Shawn and St. Denis (née New Jersey farm girl Ruth Denis) were celebrities and kept their clippings, along with frank correspondence, choreographic notes, travel memorabilia, some of the earliest motion pictures ever made, and more. He’s a dogged researcher, and some of the treasures he includes from widely dispersed archives, like the John Singer Sargent collotype of a drowsy, bare-chested Shawn drawn in the period when he was labeled “World’s Most Handsome Man” (move over, John Legend!), are even more impressive when contextualized.

Shawn’s story is compelling, but Scolieri presumes a lot. I hope readers will skim his introduction and not put the book down before diving into his narrative, because those first few pages groan with the weight of references that people outside the field are unlikely to know, and a long-winded argument positioning his research against prior Shawn biographies and memoirs, both complete and unpublished.

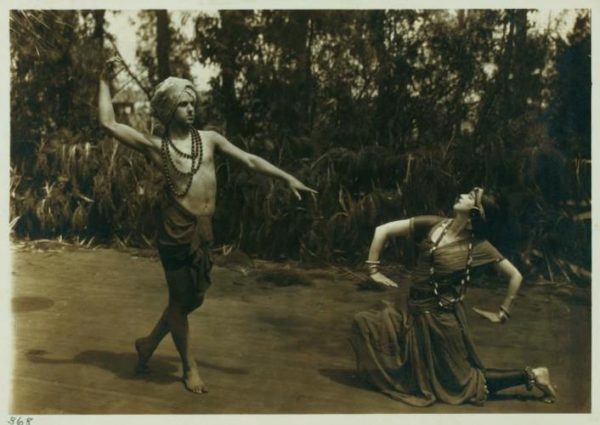

Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis performing outdoors, c. 1915. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Scolieri also makes some elisions that, at the very least, will leave many readers with misperceptions. He unearths an odd 1914 Washington Post story in a Denishawn scrapbook headlined “Student of Eugenics Closely Watching This Marriage: Union of the Splendidly Developed Dancer Ruth St. Denis and Edwin Shawn ‘the Handsomest Man in America’, May Produce Results of Great Value to the Science of Race Betterment.” First, yuck. I have no argument with the historic fact that popularized notions about Darwin, eugenics (the term was coined by Darwin’s cousin), and scientific racism were part of Shawn’s intellectual milieu, especially in his relationship with sex researcher Havelock Ellis; Scolieri has been writing about this confluence for a long time. Nonetheless, even simplistic readings of eugenic theory present the notion that the progeny of St. Denis and Shawn (who never came to be, as it turned out: after a pretty sexless marriage, they were childless) were the superhumans of which eugenicists dreamed. The idea of producing ideal bodies through dance and other athletic pursuits may have been a demonstration of a eugenically endorsed end product, but it is not eugenics as we, or the Nazis, knew it. Given the history of eugenic forced sterilization and murder, this distinction is something that no one should underplay to make a rhetorical point. Scolieri’s disclaimers are too little, too marginal.

On the conflicted construction of masculinity as seen through the lens of Shawn’s dances, Scolieri is a more reliable guide, if only because Shawn, his dancers, and approving observers of the time told us what they meant by manliness. It’s hard to remember that a male dancer scantily clad as a Hindu god would have been seen as masculine in 1917 when that same bejeweled costume would now be at home as drag, but Shawn’s early-20th-century orientalist portrayals opened the door not only to honoring diverse cultures in a time before international communications and travel were easy, they also made possible a more multifarious masculinity. Nobody would have dared to call Krishna a sissy. That Shawn would draw the interest of sex researcher Alfred Kinsey is not surprising, although some of the details are (Shawn wouldn’t send nude pictures through the mail in 1945 because he was worried about getting busted, and so sent some censored images of his younger, lead dancer/lover Barton Mumaw instead. Later Kinsey got a nude photo of a well-oiled Shawn standing on a rock, which Shawn autographed).

In this new biography, Ted Shawn is on display in all his narcissism, paternalism, hypocrisy, originality, and the dedication to creative expression that set American modern dance on its way. That’s a good thing, because being on display was Ted Shawn’s favorite way of being alive.

Debra Cash, a a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse now serving on its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance. She also serves as a Scholar in Residence at the festival Ted Shawn founded, Jacob’s Pillow, which holds many of the archival materials used in Ted Shawn: His Life, His Writings, and Dances.

Great to read this review of a new book about Ted Shawn. I will request it from the library. Thank you for making The Arts Fuse a reality.