Classical CD Reviews: Offenbach’s “La Périchole,” Aaron Jay Kernis’ Orchestral Works, and Baiba Skride plays Bartók

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Marc Minkowski’s recording of Jacques Offenbach’s La Périchole pays the composer a handsome tribute in his birthday year; violinist Baiba Skride’s new all-Bartók disc is one of the year’s best.

Jacques Offenbach’s bicentennial this year hasn’t received the same attention showered on Wagner and Verdi in 2013, Schumann in 2011, or Mendelssohn in 2009. Perhaps that’s understandable: Offenbach’s musical contributions weren’t as innovative or elevated (to use a charged term) as those four. But his dramatic antennae were keen, his gift for a tune unparalleled, and, nearly two centuries on, his music is still heard widely on screen and airways, in theaters and concert halls.

Jacques Offenbach’s bicentennial this year hasn’t received the same attention showered on Wagner and Verdi in 2013, Schumann in 2011, or Mendelssohn in 2009. Perhaps that’s understandable: Offenbach’s musical contributions weren’t as innovative or elevated (to use a charged term) as those four. But his dramatic antennae were keen, his gift for a tune unparalleled, and, nearly two centuries on, his music is still heard widely on screen and airways, in theaters and concert halls.

Marc Minkowski’s been a devoted advocate of Offenbach’s music and his new recording of the composer’s 1868 opéra-bouffe, La Périchole, pays him a handsome tribute in his birthday year.

The piece itself is a blend of farce and drama: a street singer (La Périchole) catches the eye of the Viceroy of Peru, Don Andrés de Ribeira. He wants to take her as his mistress, but, in order to keep up appearances, she can’t join his entourage unless she’s married. Enter her lover, Piquillo, who, once he learns what’s going on, is understandably furious. At any rate, Piquillo and La Périchole are married, eventually imprisoned, and, finally, sent on their way with the Viceroy’s blessing.

Offenbach’s score is a delightful mélange of Spanish-tinged musical references (seguedilles, boleros, etc.), mid-19th-century dances, and fetching melodies. The edition recorded here combines much of the 1868 original with a few numbers from Offenbach’s 1874 revision. It moves swiftly, though, never overstaying its welcome (the total performance time is just north of 100 minutes and includes dialogue).

As the title character, Aude Extrémo sings with warmth and an easy command of her part’s wide range. Over the first act her tone lacks a degree of shine, though as the performance proceeds, she settles into the role quite agreeably. Her solos in the third-act “Couplets de l’aveu” are beautifully done and Extrémo’s ensemble-work throughout is finely blended.

Stanislaw de Barbeyrac proves a bright-voiced, energetic Piquillo. A couple of breathless moments aside, he’s got the part capably in hand. So does Alexandre Duhamel, who sings the nefarious Don Andrés with a pleasing mix of power and elegance.

Minkowski draws a stylish reading of the score from Les Musiciens du Louvre. They’re not a big ensemble – just 37 players are listed – but they never sound scrawny, or turn in playing that wants for spirit and élan. The voices of the Choeur de l’Opéra National de Bordeaux also sound bigger than their small numbers (just 20!), while also singing with dexterity and full-bodied tone.

This set is filled out with a series of informative essays on La Périchole as well as Offenbach’s working methods; the libretto is also included in full, both in French and English. For Offenbach lovers and the Offenbach-curious, it’s a must. Also see critic Ralph P. Locke’s Arts Fuse review of La Périchole.

Aaron Jay Kernis’s compositional strengths and weaknesses are on full display in the Peabody Symphony Orchestra’s (PSO) new, all-Kernis disc. He’s a composer whose stylistic sensibilities and technical skills are impressive, to be sure, and there’s much to be said for his embrace of a musical language that doesn’t shy away from popular influences. Yet, to these ears at least, what Kernis writes too often seems derivative, pretentious, and/or predictable. So things go in the current release.

The album’s most substantial offering is the debut recording of Kernis’s 2015 Flute Concerto, a meaty essay, bold and dramatic, with plenty of sly, knowing moments thrown in for good measure. The first and third movements, “Portrait” and “Pavan” (respectively), are the work’s darkest. The former is marked by agile solo writing and beguiling orchestral doublings; the latter alternates somber and frenetic passages for soloist and ensemble.

In the second movement, Kernis writes a bucolic dance (with mandolin!), while the finale contains some surprising – but welcome – nods to the band Jethro Tull.

The Ian Anderson–inspired sections in that movement are, by a wide measure, the Concerto’s best: the driving blues riffs and episodes of simultaneous flute playing/singing are striking. But the material that surrounds them – a kind of faux-Celtic romp – doesn’t quite fit. What’s more, little else in the piece proves as memorable, either gesturally or thematically.

Kernis’s Air, heard here in its flute-and-orchestra adaptation, at least offers some memorable tunes and textures, even if both recall Copland a bit too closely for comfort. Still, it’s a lovely, well-shaped piece that ends about where you might expect but takes a few welcome harmonic detours before getting there.

In the Gulf War–era Second Symphony, which fills out the album, Kernis aimed to make a Big Statement. Clocking in at just around 23 minutes, though, that ambition proved a Big Ask. Still, the first movement, “Alarm,” full of hurtling tattoos and snarling melodic lines, is striking. So, with its floating melodies, is the second, “Air/Ground.” But the finale, “Barricade,” while it blusters and explodes, doesn’t offer much by way of either revelation, catharsis, or completion.

The PSO plays everything on this recording with gusto. They’re the flagship orchestra of Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory and they’ve certainly got the chops for Kernis’s involved (and often inventive) orchestral writing. While some of the music’s thicker textures and trickier licks might have been more ably served by a standing professional group, the PSO (led by Marin Alsop in the Symphony and Leonard Slatkin in the flute-and-orchestra works) plays these pieces with impressive command and sensitivity to detail. Bully for them.

Marina Piccinini, for whom Kernis composed the Concerto, is the soloist and she dispatches the composer’s often high-flying, treacherous writing with aplomb.

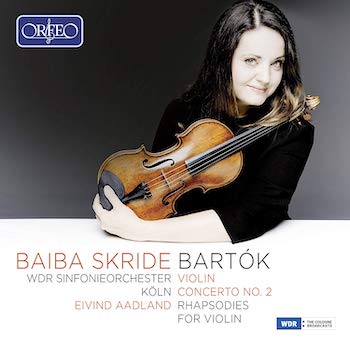

The highlight of Baiba Skride’s new all-Bartók disc might not be her formidable account of the Violin Concerto no. 2, fine though that is. For me, it was her performances of the two violin-and-orchestra Rhapsodies filling out the album that elevated this recording to among the year’s best.

The highlight of Baiba Skride’s new all-Bartók disc might not be her formidable account of the Violin Concerto no. 2, fine though that is. For me, it was her performances of the two violin-and-orchestra Rhapsodies filling out the album that elevated this recording to among the year’s best.

Those two pieces – each about 10 minutes long and steeped in Bartók’s familiar, folk music–infused style – are, in Skride’s hands, simply captivating: full of soul, fire, pathos, and humor.

In both, she balances Bartók’s sweeping lyricism and muscular acrobatics with aplomb. There’s immense strength – both of the physical and interpretive variety – in her readings, but also a winning degree of vulnerability, as the second theme of the first Rhapsody’s “Lassú” movement and the Scotch snaps of the second’s “Friss” demonstrate. In a word, everything sings, often powerfully and never brusquely.

Einvind Aadland leads the WDR Sinfonieorchester-Köln in accompaniments of spirit and color, the twanging cimbalom proving almost as much a highlight of the first Rhapsody as Skride’s brilliant performance of her part.

Skride’s reading of the Concerto is characteristically bold and grand. The outer movements are fervent and gritty, while the central variations are played with beguiling elegance and not a hint of sentimentality.

As in the Rhapsodies, Aadland leads his band in readings of sweeping energy, grandeur, and tone. Indeed, these are orchestral performances of real subtlety and nuance: just listen to the ravishing sonorities the conductor draws out in the Concerto’s middle movement (or the clarinet licks around the finale’s central part) for a sense of what I mean. No matter how cluttered or busy the score’s textures become, these are performances that want nothing for direction or purpose. All around, then, a terrific release.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Aaron Jay Kernis, Baiba Skride, Bru Zane, La Périchole, Marc Minkowski, Naxos