Book Review: A Critical Look at Barbra Streisand’s Career

By Christopher Caggiano

Ethan Mordden’s exhaustive take on Barbra Streisand may not be what diehard fans are looking for.

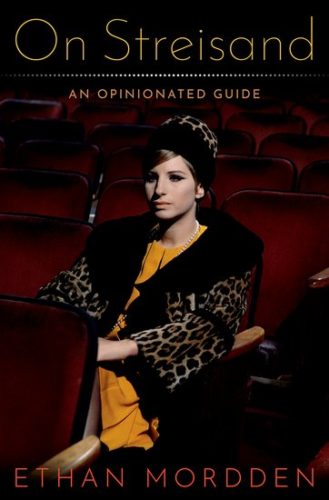

On Streisand: An Opinionated Guide by Ethan Mordden. Oxford University Press, 176 pages, $21.95

A new book from Ethan Mordden is always something to celebrate, almost invariably ending up on my metaphorical nightstand. He may be the most knowledgeable and prolific author currently writing about musical theater and abutting topics.

A new book from Ethan Mordden is always something to celebrate, almost invariably ending up on my metaphorical nightstand. He may be the most knowledgeable and prolific author currently writing about musical theater and abutting topics.

I’ve read most of Mordden’s more than 50 books, and have found something to appreciate in every one. His authoritative voice, encyclopedic knowledge, and unparalleled snark make Mordden sui generis among theater writers. You don’t have to agree with him, but you dismiss him at your peril.

Mordden’s latest book On Streisand: An Opinionated Guide may seem a bit of a surprise at first. Streisand was only in two Broadway shows in the early 1960s, and thereafter abandoned the theatrical stage. But Mordden proves himself just as encyclopedic — and every bit as opinionated — about the rest of Streisand’s career, including her multitudinous recordings and her considerably smaller number of films. Mordden’s jurisdiction extends far beyond Broadway stage.

On Streisand isn’t a biography, but rather a critical overview of Streisand’s career output. This might not be what Streisand purists are looking for, and readers expecting juicy gossip about celebrity feuds or behind-the-scenes Hollywood machinations will likely be disappointed.

An admission: I am not now nor have I ever been much of a Streisand queen, which I recognize is virtual gay sacrilege. But I haven’t been able to appreciate much of what Streisand has produced musically since The Broadway Album (1985) or for the movies since What’s Up Doc? (1972). I find her self-indulgent — in the extreme, although there’s no question she possess one of the great voices of the 20th century.

So I’m not sure if my ambivalent response to Mordden’s book is based on my personal bias against his subject or on his treatment of Streisand. But I would hazard a guess that it’s a bit of both.

Mordden takes Streisand very seriously as an artist and, despite my personal hesitations, I will say that Mordden gave me more of an appreciation of Streisand as a stylist, an interpreter, and a musician.

He goes into great detail about how she interprets a song: “Streisand finds something new in everything she sings. Yes, [that’s] true of many other vocalists—but Streisand introduces the quixotic or mysterious as well, as if her numbers had been sleeping beauties, waiting to be awakened by talent.”

Thankfully, Mordden does not traffic in blind fan worship. He usually takes a clear-eyed, balanced view of his subjects, and he does here when, offering plenty of evidence, he describes Streisand’s inability to allow anyone else to be in charge, a need for control that apparently started from her very first Broadway show and only became more pronounced as her career progressed.

On Streisand’s awkward forays into contemporary music, Mordden is philosophical: “…[W]e face the problem of a Broadway-oriented artist sampling contemporary pop without understanding that pop is often atmospheric, where Broadway is dramatic.” (Emphasis Mordden’s.) He succinctly captures the difference between the genres: “If Broadway gives us situation songs that describe activity, pop takes a snapshot of a moment.” Streisand, he argues, fares far better when she has a character to play, a journey to make throughout the song.

Mordden also isn’t afraid to take on a shibboleth among Streisand’s many defenders, a dogma embraced by Streisand herself, that her career has been hampered by sexism. He offers an alternate interpretation: “Streisand’s ‘Everybody else is wrong’ worldview did not respect Hollywood’s chain of command,” he argues. “Some people nag their partners; Streisand was nagging an industry.”

Mordden doesn’t skimp on a big-picture perspective, and that is a strength and a weakness. He offers a nuanced overview of the various strands of Streisand’s career, but the book becomes bogged down its stubborn comprehensiveness. Although there’s plenty of fascinating material for the reader to savor, the work-by-work, track-by-track treatment becomes a bit of a slog. This is especially true in the section in which Mordden digs down into Streisand’s many recordings. It might have been more engaging had Mordden been less ‘definitive’ and focused more on how the albums fit his overarching ideas about Streisand.

Mordden’s fascination with minutiae is not new, whether he’s dredging up fascinating arcana from the Broadway stage or making irresistible allusions to the opera canon. Readers should be prepared for abundant footnotes, capacious appendices, and detailed captions. And they’re really part of the fun of a Mordden book. But this documentary-heavy approach threatens to weight down the text of his books, though he usually has the polish to make most of it justifiable, or at least semi-relevant.

But, in his Streisand appreciation, Mordden can’t seem to help including too much minutiae, such as the contents of the trash left behind after Streisand’s 1967 concert A Happening in Central Park, which apparently included a Scrabble game, a Merry Widow corset, a Russian-English dictionary, and a sterling silver ice bucket. (Aren’t you glad you know that now?)

Mordden also takes a quizzical swipe at his own mother when discussing the Streisand film The Guilt Trip (2012). But in order to do so he needs to introduce the irrelevant 1958 Susan Hayward film I Want to Live! and leaves us with the image of his mother strapped into the electric chair in Hayward’s place, screaming I Want to Nag!

One of Mordden’s recent books was very similar to this one, and even had a directly parallel title: On Sondheim: An Opinionated Guide (2015). His Streisand book suffers in comparison — despite its very similar treatment and structure — because it is less cohesive, much more fragmented. He does, however, draw an apt connection between these two artists: “Like Stephen Sondheim…Streisand gets involved with projects she finds irresistible through some personal sympathy, not because they are bound to succeed.”

Christopher Caggiano is a writer and teacher based in Boston. He serves as Associate Professor of Theater at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee. His writing has appeared in American Theatre and Dramatics magazines, and on TheaterMania.com and ZEALnyc.com.

Jesus that was a bore – Opinions are like . . .