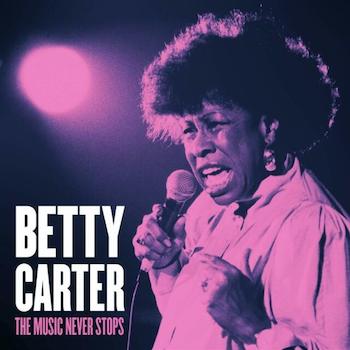

Jazz Review and Appreciation: The Music Never Stops – Betty Carter Live (Again)

By Steve Elman

A landmark concert from 1992 is a chance to rediscover Betty Carter’s greatness, to appreciate again how this artist was special to the very essence of her soul.

American jazz vocalist Betty Carter performs in New York for “The Music Never Stops” in 1992.

No one else sang like Betty Carter. She was the Thelonious Monk of jazz singing – such a distinctive and personal stylist that attempts to do things her way almost always risk being typed as imitations.

Not that it would be easy to do things her way. Begin with her sense of pitch: thrillingly flawless, demonstrated by the way she dared to shine a spotlight on hard boppish dissonances, extending “wrong” notes near the ends of tunes with the intelligence of Dizzy Gillespie. And her range: even in her 60s, when singers often lose flexibility, she reached for the climactic high note and dropped to the bottom of her voice with what sounded like off-handed ease. One can’t forget her exploitation of her “mask”: that’s the word used by some singers to describe how they color notes using the bones and tissues of their faces. And the most distinctive of all her gifts, her fluid approach to rhythm: ignoring the underlying beat whenever it suited her, floating words behind, ahead, and all around the beat – a rhythmic style so daring that it risked violating swing feel, which is supposed to be one of the touchstones of jazz singing.

The curse of the real stylist, the millstone around the neck of Carter’s reputation, is that the world tends to forget when an innovator’s work isn’t constantly renewed. Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan remain towering figures today thanks to huge discographies and techniques that can be incorporated gracefully into a modern singer’s toolkit. Carter’s recorded output is comparatively slim, and her style is much harder to master.

To remind ourselves of Carter’s greatness, we have to go back to her recordings. So, a new release of a landmark concert from 1992 is a chance to rediscover that greatness, to appreciate again how this artist was special to the very essence of her soul. The Music Never Stops (Blue Engine, 2019) documents, in excellent fidelity, Carter’s Jazz at Lincoln Center concert on March 29 of that year. Vinylphiles, please note: the 180-gram version of the set drops on May 17 this year. The rest of us will do very well with the CD version, which is already available and blessedly free of digital distortion.

Betty Carter with big band. Betty Carter with strings. Betty Carter with guest artists. Betty Carter with her working trio of the time. No matter which of these characterizations I use, you’ll have expectations about the sound of this new release. Forget them. True to Carter’s individualism, this is a unique concert concept. True to Carter’s standards, it is magnificent.

Vocalist Betty Carter — time to remind ourselves of her greatness.

Carter constructed the program and specified the stage setup in a manner unlike that of any large-ensemble concert I have ever attended – and it seems so right that I wonder why others haven’t violated the conventions in the way she did. All the musicians – including a full rhythm section for the big band composed of players different from those in her working trio – were on stage throughout the 76 minutes of music. This allowed effortless segues between tunes and seamless handoffs from one ensemble to the other. There is not a single moment of uncontrolled sound within those 76 minutes. But – and now I realize why more musicians don’t do things this way – Carter’s plan also meant that she could not rest for about 72 and a half minutes of the show, once the band had finished the overture and the introductory bars of her first tune.

And she arranged 11 of the 15 tunes she sang that Sunday afternoon, including one of the big band numbers.

Her working group was at the heart of the project. The big band is heard on five songs, the strings on only two (here’s another distinctive touch – there are only six low-register strings, with nary a violin or viola among them), and there is a single duet with pianist Geri Allen. Carter performs everything else with her trio, which does not mean that anything they play is second-rate. Cyrus Chestnut is at the piano, and his presence alone ensures brilliance. (By the way, please note that Chestnut will be at Scullers on May 30 with Carl Allen’s quartet, and he is sure to be brilliant there, too.) Carter chose to use two different drummers on the gig, Greg Hutchinson and Clarence Penn, and again the transition between them does not mean that the program even hiccups. Bassist Ariel Roland rounds out the small group. If the three other players are not as well known as Chestnut is, rest assured that Carter never chose her accompanists with anything but the most exacting standards. They think and breathe with her, especially stunningly on “Bridges,” her all-scat feature, which rises and falls, ebbs and flows, with the three supporting players staying right with her.

As in so much of her recorded work, the repertoire looks back without being nostalgic. She returns to Cole Porter’s “Most Gentlemen Don’t Like Love,” a tune she had been performing since at least 1976. “The Good Life” goes back to at least 1963. “Tight” is here, too, a signature piece in her book for at least 20 years (Jazzmeia Horn has been giving it a much-deserved revival recently, to great acclaim).

She first recorded “Moonlight in Vermont” in 1955, with Ray Bryant, and the version in this concert provides an object lesson in understanding the evolution of her style. In the early rendition, she’s already playing with tempo in ways that she would make much more dramatic, but her approach at that time was in service to musical creativity rather than song interpretation. She dips under the surface of the words just a bit; there’s a great moment when she hits a bell-like “sing” on “Telegraph cables sing down the highway.” But her early interpretation cannot match the power of the 1992 version. The one on the new CD is much looser rhythmically, delving deeply into the hypnotic mood set by the lyric. The endings are different, too – in instructive ways. The 1956 version concludes with enormous dissonance, absolutely on pitch. The 1992 version gives us one of her most dramatic uses of her mask.

Two of the big band arrangements come from another early session, led by Gigi Gryce. This is music that remained unissued until 1990, when Carter’s star had risen far enough to make her early work commercially viable. We can read Carter’s resuscitation of the Gryce charts of “Social Call” and “Frenesi” – recorded originally in 1956, released 34 years later in 1990, refurbished and played live in this show in 1992 – as a pointed commentary on material that was “new” to her discography at the time. (“Listen to how good these things sound! What a shame we had to wait so long for them to come out!”) And the irony deepens – it’s taken another 27 years for the second versions to come to market.

Here’s another lesson I learned, by comparing the original “Social Call” with this one: In the first, she stays closer to the beat, showing off her amazing ear, because the tune as written calls for big leaps and harmonic shifts (in 1956, she nailed every one of them). In the 1992 version, she deviates from the melody quickly, not bothering with those technical challenges. Instead, she takes huge risks with the tempo, inserting big silences, gaps so long that you think she can’t possibly put all the words in . . . and then she puts them all in.

I want to mention just one more revelation from this set. “30 Years,” an original, sounds like a biographical tune, more personal than any of her sardonic tunes about love. In this version, after the written lyric, ending “30 years is a long time,” she begins “singing the story” à la Sheila Jordan, something I have never heard her do in another context.

But the sum of the parts here is much greater than the realization of any individual tune. The concert gains emotional momentum as it goes along, with unforgettable results. I could rhapsodize about each track (and I have – see below). But for this sketch, it’s enough to say that hearing those 76 minutes brought Betty Carter back to life for me, if only for a tiny slice of time. I cannot sufficiently express my gratitude to Wynton Marsalis, Steve Rathe, and all the others who made it possible.

Carter died of pancreatic cancer a little more than twenty years ago, on September 24, 1998. On May 16, just a couple of weeks from now, she would have celebrated her 90th birthday. If life were not so arbitrary and unfair, there would be encomia and concerts in her honor. Instead, we have the great emptiness that yawns whenever a consummate artist moves on. Those who love her work can take great solace in The Music Never Stops. And every working singer should pause a moment on May 16, whether on stage or off, to remember.

More:

The Music Never Stops is so remarkable and so sustained as a work of art that it deserves a tune-by-tune description. I’m sure that every listener’s appreciation of the album will be personal, but here are my own impressions:

“Ms. B. C.” (Pamela Watson, arr. Bobby Watson): An up-tempo overture, written in Carter’s honor. (The title is a pun on Coltrane’s “Mr. P. C.”) The big band gets its chance to shine, and it’s a crack NYC crew, with Jerry Dodgion leading the reeds, and Lew Soloff leading the trumpets, two of the best musicians Carter could have asked for. The chart is crisply executed, with solos by tenor player Alex Foster (strong), and trumpeter Kamal Adikifu (perhaps trying a bit too hard, but this is excusable given the heavy company). And I have to note that the rhythm section – John Hicks on piano, Lisle Atkinson on bass, and Kenny Washington on drums – were all veterans of Carter’s small group. Another indication of how carefully she planned and controlled this gig.

“Ms. B. C.” segues seamlessly into a piano obbligato from Cyrus Chestnut on the other side of the stage (or maybe part of the obbligato is played by the big band’s pianist, John Hicks) which leads to:

“Make It Last,” (Bob Haymes, arr. Melba Liston), with the strings (four cellos and two basses) in a prominent role, backed by the big band. Carter is in superb voice, all over the tempo. She throws in some very daring shading, almost off-pitch. This first number defines the Carter territory; she makes other singers sound hamstrung by hewing to tempo and composed melody. However, Carter’s rhythmic adventurousness and lyric stretches begin to separate the words from their meaning – you stop listening to what the song is about, dazzled by what she does.

Another seamless segue to:

“30 Years” (Carter), with the trio only. After the written lyric, ending “30 years is a long time,” she begins “singing the story” à la Sheila Jordan. The long held note at the end is deliberately in counter-pitch to the key, true to her bop roots.

Carter sings a segue between tunes over Chestnut’s piano and moves into the first line of the next tune a cappella.

“Why Him?” (Burton Lane / Alan Jay Lerner). This is the first of three “question” tunes that Carter has worked into a medley. It’s taken slowly, with just a bit of a pulse. Memorable line: “There’s nothing but bulging . . . in his arms,” gently hinting at something more risqué. Chestnut does some fancy rubato fingering, feigning going into fast tempo, but takes his solo over the bass and drums at the same slow pace. They go into double-time leading into Carter’s return. At the end of the lyric line, Chestnut slides into a slow vamp and Carter improvises over it, using “why him” as syllabic basis for a semi-scat transition into the next tune.

“Where or When” (Rodgers / Hart) – This is the first really familiar tune on the program. She sings one chorus very freely, then hands it to Chestnut for a solo, then takes it back for one more chorus and a vamp.

She sings an introduction to the last tune of the medley with a long high note over suspended tempo, showing that she still has a pure high register.

“What’s New” (Bob Haggart / Johnny Burke) is the first tune on the program where she actually sings the melody as written. Somehow, she even turns that into a dramatic surprise. At the end of the first chorus, Chestnut drops into a slow vamp of chords and Carter repeats phrases from the lyric, stretching everything out.

Finally, there is enough of a break in the music for some enthusiastic applause.

“Tight” (Carter): Carter is all over the beat, except for the final word in each chorus, which is exactly on the beat, where it must be for the song to work. This is blended with:

“Mr. Gentleman” (Carter), taken at a furious tempo, so fast that words slide into one another. The tune was originally thought of as a sequel to “Tight,” although earlier recordings of it miss a bit of the snap of the earlier tune. It uses the same motif, the word “tight,” planted solidly on the beat. This performance puts the two compositions together, and the combination is definitive.

“Social Call” (Qusim Basheer / Jon Hendricks, arr. Gigi Gryce): The big band is suddenly back, with tenor player Lou Marini taking two short breaks. Carter begins the tune a bit conventionally, and then begins bending and re-forming the lyric as noted above.

“Moonlight in Vermont” (John Blackburn / Karl Suessdorf). The big band arrangement in this tune is by Carter herself. Full discussion above. While the big band plays it, Clarence Penn comes out to replace Greg Hutchinson behind the small group’s drum kit.

“The Good Life” (Sascha Distel / Jean Broussolle / Jack Reardon). This song has always struck me as rather insincere, glamorizing “the good life” on the one hand while trying to say that, without true love, it’s empty at its core. Carter and her trio (now with Penn on drums) make it a purely musical exercise. After a suspense-filled first chorus of piano, Chestnut goes into medium swing for one of his best solos of the show. Carter comes in for the out-chorus in the same swing feel, and reaches for a thrillingly high note at the end.

“Bridges” (BC): A wordless virtuoso piece with the trio. Carter starts with scat over a pedal point. She explores the feel with a feint into modality, and then cues the band into a rising figure that leads into the changes. Her scat ability is so superior in imagination to others’ work (even Ella’s) that it almost seems like another genre of music entirely. There’s nothing coy or silly about it – it’s serious music in bright-colored clothes. The section is so attuned to her here that you forget how difficult it must be for them to read the many changes in intensity that she introduces.

The program moves into the next tune with applause, but no perceptible break, as Chestnut gives up his seat at the piano.

“If I Should Lose You” (Leo Robin / Ralph Rainger): A duet with the late Geri Allen, whose death in 2017 deprived us of a sensitive and graceful pianist. She was a much more introspective player than Chestnut is, and Carter’s choice to sing this with her alone shows how well she knew her accompanists. After a misty keyboard introduction, Carter begins far away from the melody and stays there, soaring into space, while Allen holds things together with chords in just the right places. Allen’s solo, after one chorus from Carter, is very impressionistic, and it offers one more reason to feel grief at her passing. Carter concludes with a sweet, pure, sustained “you,” over Allen’s spare piano.

Under the applause, Chestnut almost immediately returns to the piano bench and kicks off the next tune in a bright 6/8. Carter speaks her introduction over the trio. It’s worth transcribing: “This is fun time, fun time, fun time. [She laughs a bit to herself.] Cole Porter song that you’ve all heard me do, I think, I think. If you haven’t . . . good. It’s dedicated to the men. I like singing things that are dedicated to the men. I didn’t have a thing to do with these lyrics. Cole Porter wrote ‘em. It’s just my concept, OK? Just remember that, OK? My job is to pick clever, clever, clever, clever songs. And here’s one:”

“Most Gentlemen Don’t Like Love” (Cole Porter): Carter floats smilingly above the fleet 6/8, and it really is “fun time,” as she interpolates her own asides into Porter’s words. Her comic relief is so adroit that transcription doesn’t do it justice. You will not regret it if you go to Spotify and listen to just this tune. After the last line (“They just like to kick it around”), the rhythm section hits the final chord, and Chestnut sustains it with tremolos, as Carter noodles away above him. She sings “round and round and round and round” and then speaks a transition over the piano:

“And ladies, even with the kicking, we still don’t seem to get enough. We just keep going . . . going back in there . . . and looking in his eyes . . . and saying dumb things, like . . . ” Chestnut changes key, and she sings:

“Everything I Have Is Yours” (Harold Adamson / Burton Lane), and you think she’s going to do a sensitive yin to “Gentlemen”’s yang, but no. She chuckles and says, “Oh, is that dumb . . .,” sings one more line of the lyric, and then talks it out:

“I’m not gonna finish that song. That’s too heavy. It’s too deep. But what I’m gonna do, before I do the finale, I’m gonna turn you on to a brand-new one, OK? We got a brand-new one, conducted by . . . Miss Geri Allen.”

“Make Him Believe” (Carter): The strings ease in, and Chestnut plays a rubato introduction over them. Then Carter pays off the promise of yin she snuffed out just seconds before, with her own worldly-wise song of knowing sacrifice and suspension of disbelief, achingly exquisite, magnificently sung, an emotional climax that can make you cry if you have a heart. Allen’s chart and Chestnut’s accompaniment are glorious complements. Another high note, shaded just a little bit flat, concludes.

Applause subsides, and Carter counts off a blistering tempo for the big band:

“Frenesi” (Alberto Dominguez / Leonard Whitcap). This very silly song, with its slightly racist scenario of a woman falling for a “Latin lover” in a frenzy (frenesi) of desire, was a gigantic hit for Artie Shaw in 1940. Gigi Gryce and Carter rightly burlesqued it in their 1955 recording, but here it becomes an anthem of triumph, a vehicle for Carter to pull out all the stops She takes the first chorus so fast that she can barely say the lines, then scats brilliantly for a chorus, then tosses a few phrases back and forth with the band. There’s a bit of the lyric at the end, another flick of scatting, and finally (as seems inevitable), a repetition of “Frenesi” with a long high note at the end.

But that’s not quite all. The big band, kicked off by drummer Kenny Washington, vamps for Carter’s curtain calls. She shouts, “My fans!” and you can imagine her casting her arms wide to embrace the crowd and maybe throwing a kiss. She commands the band to stand (while they are still playing) to take a bow, and finally leaves the stage.

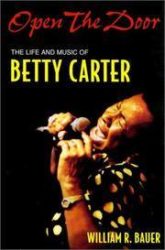

William R. Bauer’s biography, Open the Door: The Life and Music of Betty Carter (University of Michigan Press, 2002) is a valuable addition to jazz literature, clear-eyed and scholarly. It is well worth owning by anyone who wants to understand Carter’s uncompromising character as well as her art. He also offers phonetic analyses and musical transcriptions of 15 of her great performances. Even though Bauer’s prose is a bit dry, I would rather have this work in my library than some effusive hagiography. Carter deserved great care and great respect in a biographer. She was lucky to have found such a writer, and to know, at least a few months before her death, that a careful sculptor was at work on her gravestone. Since the text has been entered into the Google Books database, excerpts of it occasionally pop up if you search for any of her signature songs or the name of an important side player she worked with, along with her name.

Of the readily available Carter CDs, The Music Never Stops is now the one to own if you must own only one. But there are other great ones that will repay many listens:

The undisputed bargain is Four Classic Albums, an import reissue of Ray Charles and Betty Carter, Meet Betty Carter and Ray Bryant, Out There, and The Modern Sound of Betty Carter. The first two are early and great collaborations with other masters. The Ray Charles set is indispensable, if only for “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” the sexiest winter song ever recorded, easily shading the infantile and exploitative “Santa Baby,” which is heard far too often in the Yuletide season. The latter two are big band sessions, including “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” that rarest of all performances, a cover of a Billie Holiday classic that bests the original.

Inside Betty Carter, from 1964, is a masterpiece. The CD reissue (Capitol, 1993) is now out of print and available only from the secondary market – but the going rate to own it isn’t too prohibitive. This set includes the first, heart-stopping performance of “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most,” and one of her earliest originals, “Open the Door.” The selection of tunes is impeccable – “This Is Always” and “Some Other Time” are still neglected masterpieces of the pop song repertoire. And the accompaniment includes a rare appearance of master pianist Harold Mabern backing a singer. (Another performance note: Mabern comes to Scullers the day after Cyrus Chestnut plays there, May 31.) The CD reissue has seven tracks from a 1965 session that complement the original ones very well.

Look What I Got! (Polygram, 1988) was the first of her five CDs for Polygram and Verve, which were issued at two-year intervals (the others were Droppin’ Things [Polygram, 1990], It’s Not About the Melody [Verve, 1992], and the two below). It’s a richly rounded collection of tunes that present her creativity on a very high level, sensitively aided (inspired, even) by saxophonist Don Braden and pianist Benny Green. It won her a Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Female, and selecting highlights from it is impossible; every track is very rewarding.

Feed the Fire (Verve, 1994), recorded the year after The Music Never Stops, is an excellent companion piece to the new release, more intimate, but no less satisfying. It’s a live set recorded in London, with an all-star backing trio: Geri Allen, bassist Dave Holland, and drummer Jack DeJohnette. It is less adrenaline-driven than The Music Never Stops, and includes duets with each of the supporting players – including another take on “If I Should Lose You” with Allen. There is one standout track: a stunning rearrangement of “Lover Man,” so different from Billie Holiday’s version that it almost makes you forget Lady Day.

I’m Yours, You’re Mine (Verve, 1996) was her last recording. At 67, her voice still shows no rough edges, and her pitch control is still unerring. The tempos are mostly slow, except for a medium-up “East of the Sun.” The accompaniment is top-rate, anchored by drummer Greg Hutchinson, who plays on The Music Never Stops, with valuable contributions from pianist Xavier Davis and saxophonist Mark Shim, both of whom are talents deserving of wider recognition. It is tempting to read her penetrating extended version of “September Song” here as a valediction, but that would be a mistake. When it was recorded, she was still two years away from the diagnosis of her cancer.

The Verve CD reissue of a Carter LP from a 1970 set (originally called Betty Carter, the first one to be issued on her own label) is now called Betty Carter at the Village Vanguard. It’s a fine collection, and for one track alone well worth owning: “Ego” – Carter’s great lyric on Randy Weston’s “Berkshire Blues,” and the first of her songs critiquing men’s behavior toward women.

Regrettably, only well-to-do collectors can now afford to buy another masterpiece, The Audience with Betty Carter, which was a major release on her own Bet-Car label (from 1980, reissued on CD by Polygram, 1990). By this year in her career, Carter had refined the approach to rhythm that would characterize her work for the rest of her life. The trio featured John Hicks (who is great, despite a slightly out-of-tune piano) and Kenny Washington, both of whom play in the big band’s rhythm section on The Music Never Stops. She revisits “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most” and “Open the Door,” but there is also a memorable trio of originals (“Tight,” “Fake,” and “So . . .”) that show how much she has grown as a writer. She also sings profound versions of “Deep Night” and “Everything I Have is Yours.” The CD reissue was a significant improvement over the inferior noisy vinyl used for the original release.

Whatever Happened to Love? (Bet-Car, 1982) seems to have fallen by the wayside, and that is a shame. Verve reissued it in 1988, and then it disappeared. It was recorded at the Bottom Line in New York, with a very sympathetic rhythm section (pianist Khalid Moss, a Dayton native, has no other notable recordings; bassist Curtis Lundy was one of Carter’s most dependable sidemen; Lewis Nash is a drummer with too many credentials to recount). The lead-off tune, a remake of “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” is a real tour de force, beginning at a slow-medium tempo, doubling up, and doubling the tempo again for a breakneck finish. There is also a small string section (with harp) accompanying her on several tunes. This release was nominated for a Grammy, and it deserves to be on the market again.

Each of the above releases is hearable via Spotify.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Whew! Exhaustive — and exhausting. Makes me wanna go back to BC’s wax to relive it.

Peerless commentary on this album to date. Respect!

Thank you for this excellent review and going beyond that and really dig into the art of Betty Carter. I came late to the party and saw her for the first time on the Cosby Show, well before my interest in Jazz had started. But from the start I got intrigued, and in later years, when I learned who she was, I sought out the music and tried to make heads or tails of it all with jumpy publishing of recordings, different labels etc. The interest never left me and I’m very grateful for the work you put into the book! What I don’t understand is that, though she’s not an easy listening jazz singer, she was such a fundamental and unique part of the jazz singers landscape. Yet, no label seems to be putting any effort in giving her catalogue the proper care it deserves. As you stated, for some recording you’ll need to pay up. But my main horror now is that they even took of some of the later Verve albums from the streaming platforms. I’m happy I own that music now but it doesn’t bode well for the future.

I had the serendipity of introducing Betty Carter to my high school advisees in Oakland CA a couple of days ago – several in the group are themselves jazz musicians. I rightfully guessed none of these youngsters had heard of her before. So they got to hear her breakneck take on “My Favorite Things” recorded just across the Bay 46 years ago from the famous “The Audience with BC” collection. Scarcely twenty-four hours later, I stumbled upon a record shop in North Oakland (Hercules Records) that had a copy of “Inside BC” among their free giveaway discs by the door. “You’re giving away *Betty Carter*???” I incredulously asked the guy at the register, and he confessed that they had been unable to sell the disc for a while. So, here I am now this evening, listening to the great BC again in a fantastic recorded collection I didn’t know even existed. What a gift this disc is. What a gift Betty Carter was to all of us who were lucky to hear her live or hear her recorded legacy now.