Visual Arts Review: Two Fabulous Female Painters — Isabel Bishop and Emily Mae Smith

By Sophie Lellman

These exhibitions present two very different ways of engaging with gender, both raising the question of gaze.

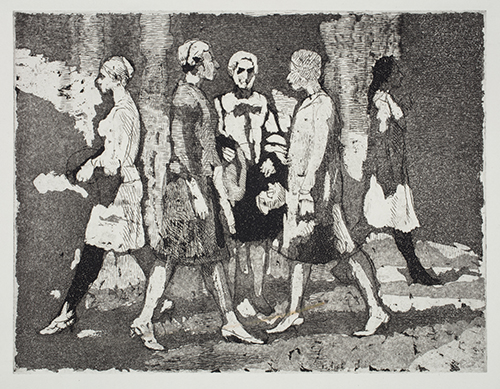

Isabel Bishop, “At the Noon Hour,” 1935. Photo: John Polak.

Most people who care anything at all about art can likely tick off the names of a half-dozen or more male painters, but would be hard pressed to come up with more than three female painters. Recently, the imbalance of female artists in museum exhibitions and collections has received considerable scrutiny and criticism. Two wonderful exhibitions currently on view in central New England do their small part towards evening the score.

Isabel Bishop’s Working Women: Defying Convention is on exhibit at the Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, MA through May 26. The exhibition is part of a citywide collaboration of art shows, programs, and gatherings that celebrate women at work. The show presents over 100 paintings, etchings, drawings, and aquatints from all stages of Bishop’s creative process. The collection also includes a number of never-seen-before pieces provided by the artist’s granddaughters.

Isabel Bishop (1902-1988) was a painter of the Fourteenth Street School, working in New York. The Fourteenth Street School, preceded by the Ashcan school, included painters Reginald Marsh, Arnold Blanch, Raphael and Moses Soyer, and Edward Laning, and focused on redefining realist painting, often incorporating Renaissance techniques and focusing on modern, urban subjects. Bishop painted primarily subjects she observed in New York’s Union Square, nearby her studio. Her paintings focus on scenes of women on their lunch breaks, chatting or eating at lunch counters, riding the subway, and later focused on students walking through Union Square.

Bishop once said of her career, “I didn’t want to be a woman artist, I just wanted to be an artist.” Yet she was also keenly aware of how being a woman affected her artistry. “I hope my work is recognizable as being by a woman,” she explained, “though I would never deliberately make it feminine in any way, in subject or in treatment. But if I speak in a voice that is my own, it’s bound to be the voice of a woman.” This is an accurate assessment of her work’s impact. It is certainly not overtly feminist yet, in depicting women at work, Bishop both chronicled and (perhaps) celebrated the cultural change that came about when women entered the workforce, primarily as a result of the World Wars.

Bishop’s treatment of her subjects reveals a distinctly female perspective. This is most obvious in her depictions of women’s relationships with each other, as seen in “At the Noon Hour” (1935) and “Double Date Delayed No. 1” (1948) in which two women lean in front of their male companion to converse with each other. It is also reflected in her depictions of the female body. Unlike other painters of the Fourteenth Street School, whose depictions of women were often sexualized — for example, Reginald Marsh’s “Merry-Go-Round” (1938) — Bishop’s women were ordinary. Often with rumpled clothing, introspective expressions, and natural poses, Bishop’s vision of women are unidealized. Her nudes are also unique in that the women are always active: reaching, looking, moving about. They do not exist simply as statues or objects for the male gaze.

Isabel Bishop, “Girls Outdoors,” undated. Photo: John Polak

Emily Mae Smith (b.1979) is a painter working today. An exhibition of ten of her paintings is being shown at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut as part of the museum’s Matrix series, which showcases emerging and under-recognized contemporary artists. Her work is on exhibit through May 5.

Smith’s shimmering oil on linen paintings address social and political issues including gender, sexuality, and capitalism with cleverly layered symbols which viewers are invited to decipher. Her avatar, a broom-like figure presented in many of the works, is inspired by the broomstick character in Disney’s 1940 movie Fantasia.

Emily Mae Smith, “Brooms with a View,” 2019. Photo: Charles Benton. Courtesy of Simone Subal Gallery, New York.

“Unruly Thread” (2019) is the work most obviously about gender. In this painting, a thread that turns from blue to pink and back again passes through the eye of a needle which, personified by the addition of lips, represents a woman. At the place where the thread passes through the eye of the needle, it is pink. The background of the painting is also a pink to blue gradient. The repeated use of the blue-pink gradient reflects the spectrum of gender presentation — but it could also be read as a reference to sexuality.

Other paintings, such as “The Drawing Room” (2018) and “Brooms With A View” (2019) are references to Alfred Tennyson’s poem The Lady of Shalott, which readers of L.M.Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables series may recognize as Anne’s best loved poem. In the text, a medieval woman locked in a tower is compelled to weave the images she sees reflected in a mirror. She is forbidden from looking out the window. One day, she can’t resist looking out, which triggers a deadly curse. Drawing on her distinctive style and rich symbolism, Smith presents a feminist retelling of this tale.

These exhibitions present two very different ways of engaging with gender, both raising the question of gaze. Both are about the act of looking in the context of female subjects and female creators. In Bishop’s work, none of the women she depicts ever look directly out of the painting at the viewer. They look at other women, they look at newspapers and books, they look at their own bodies. In Smith’s work, it is striking that her broom-avatars have no eyes, though eyelashes can be seen when they are shown in side-profile. What does that have to say about female subjects and female viewers? Visit these exhibitions and decide for yourself.

Sophie Lellman graduated from Macalester College with a BA in Linguistics. She is currently working on literary translation from Portuguese