Visual Arts Review: “Toulouse Lautrec and the Stars of Paris”

By Charles Giuliano

This crowd-pleaser of an exhibition, dedicated to an accessible, beloved artist, is a gift to the citizens of Boston and Everett, as well as to the general public.

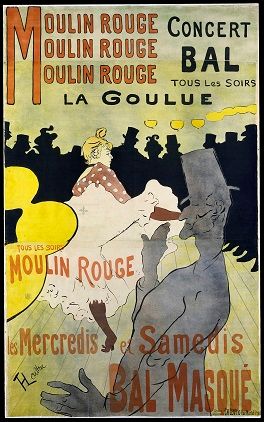

“Moulin Rouge: La Goulue” 1891, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: courtesy of the MFA

Born into a noble family, Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901), was known professionally as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Generations of inbreeding resulted in rare medical disorders. Both of his legs were broken in childhood and, despite numerous procedures, they failed to heal. He grew into an adult with a normal torso who was just 4ft 8in tall.

In 1867, a brother was born who lived a year. His parents separated and he lived with his mother in Paris. He was in line to inherit the title of comte. Because of chronic illness he was unable to pursue a profession appropriate to his social rank. From the age of eight he displayed an ability in drawing. His mother supported his career and established a museum after his death.

In a career of some 15 years the artist created an enormous oeuvre: a thousand paintings and water colors, five thousand drawings, 350 posters and prints.

The special exhibition Toulouse Lautrec and the Stars of Paris (through August 4) is a collaboration between the Museum of Fine Arts and The Boston Public Library. Their great combined depth in prints and posters is supplemented with loans from other museums. In addition to his signature graphic works the exhibition has expanded our appreciation of his vision with paintings, photographs, and sculptures by other impressionist and post impressionist artists.

There are several newly restored films by Auguste and Louis Lumiere, contemporaries of Toulouse Lautrec who survived into the mid 20th century. Large projections of their innovative motion pictures include a street scene of Paris with carriages (which is given a lively sound track). Two others focus on iconic dances: the Can Can and an emulator of the serpentine dance popularized by Chicago born Loie Fuller.

The “Stars” of the exhibition title refers to Lautrec’s involvement with cabaret, dance hall, and theatrical performers Yvette Guilbert, Jane Avril, Aristide Bruant, Marcelle Lender, May Belfort, and Loie Fuller.

This crowd-pleaser of an exhibition, dedicated to an accessible, beloved artist, is a gift to the citizens of Boston and Everett, as well as to the general public. During the month of June, holders of BPL library cards (two adults and up to six children) will be admitted free. Because of sponsorship from the soon to be opened Encore Boston Harbor, Everett’s new luxury resort and casino, employees and Everett citizens with proof of residence will be admitted free during the run of the show.

Lithography was invented in 1796 by German author and actor Alois Senefelder. During the fin de siècle in the City of Lights the technique was developed into a means of creating large format, cheap, multi-colored advertising posters. Lautrec embraced commercial commissions as a means to supplement support from his family.

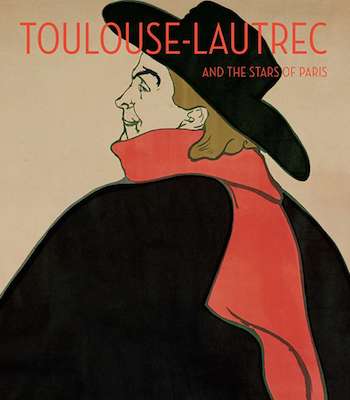

“Aristide Bruant in His Cabaret,” 1893. Photo: courtesy of the MFA

Lautrec rarely strayed from bohemian Montmartre, with its array of brothels, bars, cabarets, and music halls. He celebrated the demi-monde he inhabited. Though he was high born, his deformity served as camouflage; he observed, close at hand and with uncanny wit and insight, the colorful underworld of entertainers, whores, johns, and apaches.

Lithography, which could reach an enormous scale, was a perfect medium. The artist draws directly onto smooth limestone slabs with greasy crayon or ink (tusche). The stone is then etched so that areas not drawn upon retain water. When greasy ink is rolled over the image it is repelled by wet areas. To make multi-colored posters, separate stones are layered in registers.

The first commission “Moulin Rouge: La Goulue,” 1891, (190 x 116.5 cm) is the largest poster in the exhibition. While impressive in scale, the picture lacks the succinct, graphic punch of, for example, versions of Aristide Bruant which were created just two years later. A pair of these posters, among the strongest in the exhibition, dominate the first gallery of the exhibition.

Bruant is the only male of the “Stars” in this show. A remarkable showman and self promoter. He was a cabaret artist known for insulting audiences. He dressed with minimalist flair, featuring a black cloak, broad brimmed black hat, and a swath of red affected by a flamboyant scarf. Out of these elements Lautrec created a compelling “pop” icon. It is so stunning an image that it makes one think of Warhol’s signature “Marilyns.”

Compared to the image of the powerful, masculine Bruant, the posters and luxury prints featuring women entertainers are more challenging, meticulous, and complex. It took more nuanced observation — and insightful, often sketchy rendering — to evoke the power of their personas.

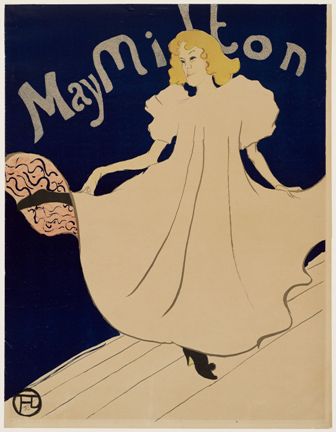

May Milton, 1895. Photo: courtesy of the MFA

Yvette Guilbert embodied a number of intriguing negatives She wasn’t much of a singer and half spoke her material. Her body was scrawny and flat-chested. Lautrec exaggerates her sharp beak of a nose and pointy chin. It is said that what Guilbert lacked in looks and talent was more than compensated for by her charisma. One must look long and hard in order to discern what he sees in her. They are not in any sense pretty pictures.

The British cabaret star, Jane Avril, was a skilled and graceful dancer. The images of her are more attractive. Another Brit, May Milton, was also said to be short on talent and beauty. During Picasso’s early Lautrec period, her familiar poster can be seen on the wall of the studio in his 1901 painting “The Blue Room.”

In order to create these images of celebrated women, it appears that Lautrec haunted them — the better to capture their essence. His interest in Marcelle Lender could best be described as an obsession. With the stage name of Anne-Marie Marcelle Bastien, she was beloved as a star of opéra-bouffe or light opera. For a German arts magazine he created a technically complex, delicately colored, layered profile portrait. It was poorly received and the coeditor who commissioned it, Julius Meier-Graefe, was fired. When Lautrec offered another portrait of herself to Lender, she rejected the gift. She told a friend that he was a “horrible man.”

Lautrec may well have been, but he overcame a brief life of excruciating pain to leave a remarkable body of work. This small, tormented man cast a giant shadow.

Charles Giuliano is completing his sixth book Counter Culture in Boston: 1968 to 1980s. He is well along with the next one Boston Fine Arts: Museums, Galleries and Artists.