Jazz Recommendations: The Test of Time, 2018

By Steve Elman

Here’s a look back at the history of jazz recordings and a selection of ten of the best, plus one release from 2018 that has a good chance of being one of my favorites for many years to come.

A 1958 photo of Earl Hines with his band. Photo: Dennis Stock

Four years ago in the Fuse, I provided thumbnail sketches of ten classic jazz CDs that I thought would make great holiday gifts for the jazzperson on your list. Two years ago, I selected another ten. Now it seems to be time for another round.

My rationale: I knew that I couldn’t possibly listen to even a smattering of all the jazz CDs released in the previous twelve months, and, even so, only time could determine for me whether any of them had lasting value. So the idea that I could select “best recordings of the year” seemed slightly absurd, and I thought that that task should best be left to my big-eared colleagues.

But I also felt that readers should have a gift guide in so far as my poor powers would allow. So here’s another look back at the history of jazz recordings and a selection of ten of the best, plus one release from 2018 that has a good chance of being one of my favorites for many years to come.

I think any one of these releases would be received gratefully by a person who listens with both ears. I apologize in advance if you can’t wrap them before December 25 . . . but be of good cheer – post-Christmas sales may give you the chance to get some of them at a bargain.

(By the way, I think my previous recommendations have held up pretty well. See below if you’d like to review the selections from 2014 and 2016.)

Frank Kimbrough (p), Scott Robinson (reeds), Rufus Reid (b) and Billy Drummond (dm): Monk’s Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk (Sunnyside, 2018)

This is my ringer for 2018, the exception that I hope proves the rule. I cannot guarantee that in five years, I will listen to it with the same joy I had when I heard it a week ago, but I cannot slight it by leaving it out. Here, for the first time in a single set, are all 70 of the known compositions of Thelonious Monk (even including “Eronel,” of which Monk actually only wrote a note or two), performed by four seasoned interpreters who know the music well and give each tune a spirited reading. The group is closest in spirit to Monk’s quartet with Johnny Griffin, or to his early Columbia quartet dates with Charlie Rouse. Each of the six CDs has a surprise or two, thanks to Robinson’s extraordinary ability as a multi-instrumentalist. The usual tenor-piano-bass-drums combination is varied just when you need it, with his bass sax taking over on “Little Rootie Tootie” or “Bemsha Swing,” his double-belled echo cornet providing a call-and-response approach to “Bluehawk,” his bass clarinet smoothing out the slow lope of “Locomotive,” and his contrabass sarrusophone (!!) adding unexpected rumbling to the very familiar “Misterioso” and “Straight No Chaser.” I even had the wonderful experience of hearing a Monk tune for the first time, something I thought I’d outlived long ago – it’s one called “Sixteen,” something from an early Blue Note session that I must have overlooked. Are there flaws? Of course. Maybe “Monk’s Point” shouldn’t have been done as if it’s about to fall apart at the seams. Maybe the piano is a bit out of tune on “’Round Midnight” and “Work.” Maybe “Oska T.” should have been done just a bit faster. If Robinson slips a bit on the toughest lines, “Gallop’s Gallop,” “Four in One,” and “Skippy” give even the great masters fits, so no demerits there – and he kills it on “Criss Cross” and “Friday the 13th.” (It always does a listener good to remember Monk’s zen-like aphorism, “Wrong is right.”) In fact, so many things are right, and so many risks are successful – like “Ugly Beauty” played in waltz tempo, bassist Rufus Reid’s role as lead instrument on “Monk’s Mood” and “Blue Monk,” the hint of a boogaloo beat on “Two Timer,” and a touch of free playing on “Jackie-ing,” that my enthusiasm is almost untempered. Above all, special kudos to leader and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who plays every note authentically without sounding imitative of the master – an achievement of the highest order. The tunes provide about six hours of pleasure for you or your giftee, and this sublime experience will only set you back about $70.

This is my ringer for 2018, the exception that I hope proves the rule. I cannot guarantee that in five years, I will listen to it with the same joy I had when I heard it a week ago, but I cannot slight it by leaving it out. Here, for the first time in a single set, are all 70 of the known compositions of Thelonious Monk (even including “Eronel,” of which Monk actually only wrote a note or two), performed by four seasoned interpreters who know the music well and give each tune a spirited reading. The group is closest in spirit to Monk’s quartet with Johnny Griffin, or to his early Columbia quartet dates with Charlie Rouse. Each of the six CDs has a surprise or two, thanks to Robinson’s extraordinary ability as a multi-instrumentalist. The usual tenor-piano-bass-drums combination is varied just when you need it, with his bass sax taking over on “Little Rootie Tootie” or “Bemsha Swing,” his double-belled echo cornet providing a call-and-response approach to “Bluehawk,” his bass clarinet smoothing out the slow lope of “Locomotive,” and his contrabass sarrusophone (!!) adding unexpected rumbling to the very familiar “Misterioso” and “Straight No Chaser.” I even had the wonderful experience of hearing a Monk tune for the first time, something I thought I’d outlived long ago – it’s one called “Sixteen,” something from an early Blue Note session that I must have overlooked. Are there flaws? Of course. Maybe “Monk’s Point” shouldn’t have been done as if it’s about to fall apart at the seams. Maybe the piano is a bit out of tune on “’Round Midnight” and “Work.” Maybe “Oska T.” should have been done just a bit faster. If Robinson slips a bit on the toughest lines, “Gallop’s Gallop,” “Four in One,” and “Skippy” give even the great masters fits, so no demerits there – and he kills it on “Criss Cross” and “Friday the 13th.” (It always does a listener good to remember Monk’s zen-like aphorism, “Wrong is right.”) In fact, so many things are right, and so many risks are successful – like “Ugly Beauty” played in waltz tempo, bassist Rufus Reid’s role as lead instrument on “Monk’s Mood” and “Blue Monk,” the hint of a boogaloo beat on “Two Timer,” and a touch of free playing on “Jackie-ing,” that my enthusiasm is almost untempered. Above all, special kudos to leader and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who plays every note authentically without sounding imitative of the master – an achievement of the highest order. The tunes provide about six hours of pleasure for you or your giftee, and this sublime experience will only set you back about $70.

John Coltrane: Ballads (Impulse, 2008; originally 1963)

Speaking of sublime, this session is the single greatest achievement of Coltrane’s relationship with producer Bob Thiele. Thiele urged Coltrane to play a group of neglected standards, all in relaxed to dead-slow tempo, and the saxophonist met the challenge brilliantly. With these eight tunes, Coltrane redefined the art of jazz ballad playing. You never get tired of hearing it, and that’s no cliché.

Wynton Kelly and Wes Montgomery: Smokin’ at the Half Note (Verve, 2005; originally 1965)

The Kelly-Montgomery partnership wasn’t well documented, but this session shows how good it was. There’s been another very good set issued, from 1966 (Smokin’ in Seattle: Live at the Penthouse [Resonance, 2017]), but that’s taken a radio broadcast, and a couple of the tracks are incomplete. The Verve date was professionally recorded, and it is the one to have. Kelly was nominally the leader, and he certainly deserves the attention this set gives him, but the date feels more like a meeting of equals. Montgomery is undoubtedly the more original stylist; his commercial success was just beginning, and he is at full strength here as a soloist and as a song interpreter.

Duke Ellington: . . . And His Mother Called Him Bill (Sony Canada, 2016; originally RCA, 1968)

Duke Ellington: . . . And His Mother Called Him Bill (Sony Canada, 2016; originally RCA, 1968)

No greater love hath ever been shown on record than this exquisite tribute to Ellington’s partner Billy Strayhorn. The session contains some of the most feeling music ever made in a jazz context. Of all the greatness here, there are two indelible moments: Johnny Hodges’ solo on “Blood Count,” which shakes a furious fist at the Reaper for stealing a friend and artist, and Ellington’s impromptu solo piano version of “Lotus Blossom,” recorded as the session was ending, with band members packing up around him and suddenly falling to a hush as they realize Duke is having an unexpectedly private moment of grief. The Canadian reissue includes alternate takes, almost as good as the ones finally chosen.

Bill Frisell [produced by Hal Willner]: Unspeakable (Nonesuch, 2004)

One of these years, I’ll decide which of Hal Willner’s all-star composer tributes (Nino

Rota? Monk? Kurt Weill? Mingus?) should be included on this list, but for now, there is no doubt that this session with guitarist Bill Frisell is one of his towering achievements, and an ear-opening adventure for a fully-attentive listener. Willner isn’t just producing here; his collaboration includes “composing” of a sort, adding samples, distorting the sound creatively, and plenty of studio tricks I don’t completely understand, all of which contribute to a distinctive sonic atmosphere in which Frisell thrives. The CD is a thoroughly modern work of art which promises to be timeless.

Stan Getz [improvisations on compositions by Eddie Sauter]: Focus (Verve, 2005; originally 1961)

This is one of the most audacious music experiments in history, all the more remarkable for its sheer beauty and the ingenuity of its star. Sauter was known for his classical-level musical sophistication when he co-led a 1950s big band with pianist Bill Finegan. For this date, he prepared seven through-composed charts for strings, with no obvious “holes” for a front voice. Getz was given the task of improvising solo parts over the string charts. The two elements – one completely written, one completely unwritten – coalesce magically. No one else ever tried such a thing again, possibly for the same reason that no one ever tried to build another Taj Mahal.

Dizzy Gillespie: An Electrifying Evening (Verve, 1999; originally 1961)

Dizzy Gillespie: An Electrifying Evening (Verve, 1999; originally 1961)

This date is perfect Gillespie, the only Diz CD you must own, even though it will inevitably make you want to own more. It was recorded live in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, with one of the trumpeter’s great small groups, including the incandescent Leo Wright on alto sax and an up-and coming Brazilian pianist named Lalo Schifrin who hadn’t yet written anything outside of jazz, much less the TV theme for Mission: Impossible. Dizzy’s trademark solo approach, blending the staccato and legato for maximum drama, was never captured more effectively, and the support throughout is the very definition of simpatico.

Charles Mingus: Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (Impulse Classics, 2007; originally 1983)

The best of Mingus’s recordings for any one person on any one day depends on that person’s mood. I just re-heard Oh Yeah, an LP I remembered as mostly a good-natured burlesque, and discovered that I had forgotten how strong it is and what mighty contributions Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Booker Ervin, and Jimmy Knepper make to the party. The leader’s Columbia dates are rich and wonderful. The later Atlantics have some unforgettable performances. Gunther Schuller’s reconstruction of his masterpiece, Epitaph, is a landmark achievement. But for overall excellence and solo strength, this one is hard to beat, and it gives lasting pleasure no matter what your mood. Despite the fact that “Haitian Fight Song” appears here as “Hora Decubitus” and “Goodbye Pork-Pie Hat” appears here as “Theme for Lester Young,” you hear the leader, along with soloists Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin and Jaki Byard, at the absolute top of their game.

Oscar Peterson: Tracks (Verve, 1994; originally MPS, 1971)

Oscar Peterson’s gifts as a pianist were prodigious. But some of his work sounds as if his technique serves as camouflage for genuine feeling. In the worst cases, you might as well be listening to someone type. This session was something very different, with a deeply-felt evocation of his great influence Art Tatum on “Honeysuckle Rose,” a Bill Evans-ish approach to “Dancing on the Ceiling,” and even a nod to Thelonious Monk by doing one of Monk’s signature tunes, “Just a Gigolo,” and decorating it with stride. There’s plenty of show for those who like that sort of thing – “Give Me the Simple Life” is anything but, and “Django” and “A Child Is Born” are virtuosic, even hyperdramatic – but in the main, the motto of this recording seems to be that, at least for once, music trumps display.

Lucky Thompson and Oscar Pettiford: Lucky Thompson Meets Oscar Pettiford (Fresh Sound, 2006; reissue of original LPs Lucky Thompson Featuring Oscar Pettiford, Vols. 1 & 2 (ABC, 1956 and 1957) and two-LP reissue, Dancing Sunbeam (Impulse, 1976)

It is hard for me to think of two jazz musicians more unjustly neglected than saxophonist Thompson, an always-elegant stylist whose work resists any easy characterization, and bassist-cellist Pettiford, the bop era’s Jimmy Blanton. Pettiford died in 1960, a few weeks short of his 38th birthday. Thompson lived much longer, dying in 2005 at 81, but he had a contentious relationship with the music business, and stopped working in music entirely after turning 50. This release brings together every important recording the two made together, and every track shows what a beautiful and satisfying partnership it was. It can be listened to for simple atmosphere, but if you take the time to hear it with both ears, you will be eminently rewarded.

Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra: A Study in Frustration: The Fletcher Henderson Story (Columbia, 1994; 3-CD boxed set, a reissue of material originally in a 4-LP boxed set with the same name from 1961)

God bless Sony BMG and CBS for keeping this landmark set in print. The original selections from the Henderson discography were made by John Hammond in 1961, and they represent the best of the greatest jazz being made in New York City from 1923 to 1938, as Henderson’s band grew from a little dance band building on New Orleans style to the most important exponent of black swing. In 1994, Frank Driggs oversaw a beautiful CD reissue with reverential care, assiduous remastering, and just the right amount of design updating. Here are definitive performances by Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Don Redman, Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge, and many other giants of the period. This set arguably set the pace for all the historic reissues that came after. And yet, there is other Henderson material that, to this day, is calling out for a similar treatment (see The Waiting Room below.)

One more idea: let the receiver decide with a $100 Mosaic Records Gift Card

Michael Cuscuna”s Mosaic Records sets the bar today in the production of historic reissues with its diligent work compiling comprehensive surveys of particular jazz artists on particular labels, and it keeps re-setting that bar higher every year. However, each of its beautiful sets is only issued in a limited edition, and thus many hugely important Mosaic releases are out of print and fall outside the scope of my survey here – for example, the complete Capitol recordings of Mildred Bailey; all of the Django Reinhardt – Hot Club of France recordings on HMV and Swing; the complete Blue Note recordings of Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell and Herbie Nichols; the complete Mercury Max Roach Plus Four recordings; all of the Air – Henry Threadgill dates on Novus and Columbia; and 150 others. All are gone now, or available only through the secondary market. But a gift-giver could hardly go wrong by opting for a Mosaic Gift Card. There are seven mouth-watering sets currently on sale, and I can give no higher recommendation than to tell you I spent my money on the Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop concerts from 1964 and 1965, and The Savory Collection – broadcast recordings collected by Bill Savory from 1935 – 1940, of which only a handful have ever appeared on LP or CD, including broadcasts of Fats Waller, Lionel Hampton, John Kirby, Mildred Bailey, and Count Basie with Lester Young (local color: three of the Basie tracks were recorded in Boston).

More:

Here are the CDs I have previously recommended, alphabetically by artist:

Jane Ira Bloom: Sixteen Sunsets (Outline, 2013)

Jaki Byard (with Joe Farrell): Jaki Byard Quartet Live! (Prestige, 1966) and The Last from Lennie’s (Prestige, 2003)

Ornette Coleman: Sound Grammar (Phrase Text, 2006)

John Coltrane: Coltrane’s Sound (originally Atlantic, 1964)

Ella Fitzgerald: Twelve Nights in Hollywood (Verve, 2009)

Bobby Hutcherson: Wise One (Kind of Blue, 2009)

Keith Jarrett & Charlie Haden: Jasmine (ECM, 2010) and Last Dance (ECM, 2014)

Sheila Jordan: Portrait of Sheila (originally Blue Note, 1963)

Steve Kuhn (with Steve Slagle and Sheila Jordan): Life’s Backward Glances – Solo and Quartet (ECM, 2008; a boxed-set reissue of Ecstasy (1975), Motility (1977), and Playground (1980)

Shelly Manne (with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie Costa): 2 3 4 (Impulse, 1962) [reissued by Poll Winners (2013) as a single CD with Modern Jazz Performances of Songs from My Fair Lady [Contemporary, 1957])

Modern Jazz Quartet: European Concert, Vols. 1 and 2 (Collectables Jazz Classics, 2006)

Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane: At Carnegie Hall (Blue Note / Thelonious, 2005)

George Russell: The African Game (Blue Note, 1983)

SF Jazz Collective: Live 2010 – 7th Annual Concert Tour – The Works of Horace Silver plus New Compositions (SF Jazz, 2010)

Archie Shepp: The Way Ahead (Impulse, 1969)

Horace Silver: The Jody Grind (originally Blue Note, 1967)

Martial Solal: Live at the Village Vanguard – I Can’t Give You Anything but Love (CAM Jazz, 2009)

Tierney Sutton Band: On the Other Side (Telarc, 2007)

Art Tatum: 20th Century Piano Genius (Verve, 1996)

Matt Wilson’s Big Happy Family: Beginning of a Memory (Palmetto, 2016)

The Waiting Room

These brilliant recordings ought to be back on the retail market so that modern listeners can acquire their own copies, but they have either been withdrawn from sale or have been never reissued properly. Maybe someday . . .

These two start a list of material to watch for. I hope it won’t get longer.

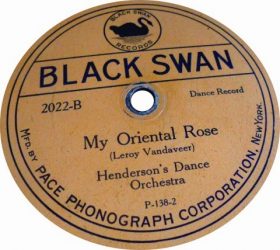

Fletcher Henderson: The Vocalion, Paramount, and Black Swan Recordings

EMI now holds the rights to the Fletcher Henderson Vocalion recordings of the 1920s and 1930s, which in themselves could be the foundation of a definitive reissue package; in fact, French RCA began that effort in the 1990s. but the presentation was not ideal and it never had wide distribution. What is really needed to round out the Vocalion material is a contemporaneous catalog of original Hendersonia, recorded for Paramount and for the first label owned by African-Americans, Black Swan. The rights to those recordings were acquired by the independent record visionary George H. Buck, so some negotiation would be necessary to bring the best of the trove together in a musically significant way. This important material needs just three people to reissue it correctly – a dedicated producer backed by executives at EMI, a lawyer to work out the rights issues, and a great craftsman to oversee the remastering.

Earl Hines: Quintessential Recording Session (Chiaroscuro, 1970); Quintessential Continued (Chiaroscuro, 1973) and Quintessential ’74 (Chiaroscuro, 1974)

These three solo piano recordings will be a revelation to anyone who thinks of Hines as “that guy who played with Louis Armstrong in the old days,” or as the grinning showman who led so many trio dates of middling quality. In these recordings, he revisits some of the ancient tunes he turned into jazz masterpieces, and stuns with his invention and daring. They cry out for restoration to the market in a commemorative set with sensitive commentary.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.