Jazz CD Review: Dexter Gordon and Woody Shaw — From Out of the Past

These albums, featuring Woody Shaw and Dexter Gordon, are illuminating to listen to side by side.

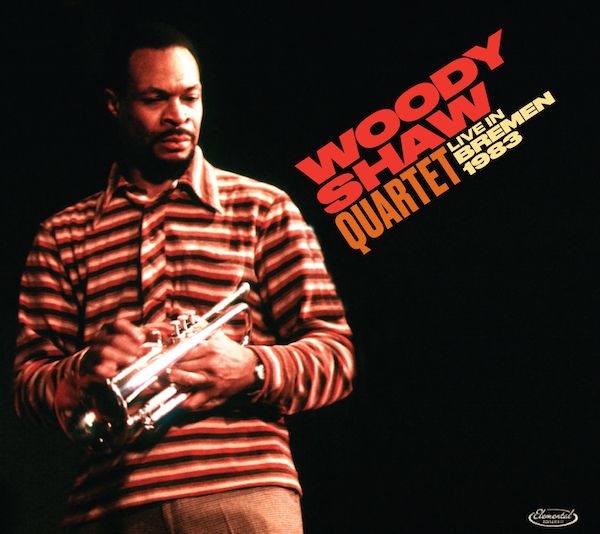

Dexter Gordon Quartet, Espace Cardin 1977 and Woody Shaw Quartet, Live in Bremen 1983 (Elemental Music)

By Steve Provizer

Most jazz listeners know the work of saxophonist Dexter Gordon. His career goes back to the early ’40s. He wasn’t in the first wave of boppers, but he was close, moving swiftly from swing into the new music pioneered by Charlie Parker and co. He forged an individual sound early on and was a force for decades, except during the ’50s, when drugs and incarceration took him off the scene. He became fed up with the racial scene in the US and spent most of his time in Europe until his triumphant return to the U.S. in 1976. Trumpeter Woody Shaw may be a bit less well known. He rose to prominence in the ’60s, after his association with Eric Dolphy and Shaw, like Gordon, spent a lot of time in Europe. By the early ’70s, the trumpeter had become a bandleader, recording often. Shaw and Gordon performed and recorded together in the ’70s.

Elemental Music offers us two previously unreleased recordings: Dexter Gordon Quartet, Espace Cardin 1977 and Woody Shaw Quartet, Live in Bremen 1983. These two musicians did perform and record together, but they don’t play together on these releases, so I assume they have been released together to try and build a buzz.The recordings do share some elements: associated musicians, similar eras, recorded live in Europe. But the DNA of the eras in which these two musicians came of age — the 1940’s versus the ’60’s — underlay significant differences in the two albums.

The Gordon sides were mastered with a fairly large amount of room ambience from the Espace Cardin. There’s also an attempt to recreate the feeling of the concert by including snatches of the saxophonist warming up along with his byplay with the audience. I can’t say these choices drew me in, but some listeners might find them immersive.

The first tune, “Sticky Wicket” is an original blues by Gordon. He introduces it to the audience in his usual droll fashion: “Sometimes in the game of cricket, one has a sticky wicket.” Dexter is a master of the saxophone who could draw on on a multiplicity of stylistic influences. To me, what set his playing apart was how he combined these elements, his note placement, and his easily identifiable sound. The timbre of his tenor is fairly round, with some edge, and he plays with an almost laconic, behind-the-beat sense of time. “Sticky Wicket” lets Gordon demonstrate his wide vocabulary of blues approaches. To a large extent, his handling of the blues goes back to his first mature stages as a musician. The difference in this go-round is that he shows how much he’s listened to John Coltrane. His long quote of Trane’s song “Cousin Mary” dots that “i.” French bassist Pierre Michelot’s playing is solid and his soloing is out of the bop playbook — Percy Heath comes most to mind. Although his career was moribund during the ’50s and ’60s, pianist Al Haig was a seminal bop player in the ’40s, playing with Bird and many others. His performance is in the Bud Powell mold. He “got” Bud, but found a recognizable voice of his own. Kenny Clarke is also a foundational bop player; a peerless timekeeper. The balance of the recording might have been improved if his drums had been put a little lower in the mix.

“A la Modal” is a variation of Miles Davis’ “So What.” Gordon is on soprano here. Again, we hear him warm up a bit, and tune up, before the band gets going. Haig sets up repeated patterns and continues them as a long intro vamp until the melody arrives. Dexter’s solos contain echoes of Coltrane’s soprano playing, although Gordon doesn’t take it “outside” and leaves more space than Trane. Repeated eighth notes, patterns, scoops, and other Dexter-isms mark his soprano style. Gordon customarily uses a large number of musical quotations in his solos. It’s second nature for him to start a phrase, recognize it, and then finish the phrase as a quotation. One quote, this one from “My Favorite Things,” is another specific nod to Coltrane.

Haig’s modal playing shows a fine understanding of this less restrictive approach to harmony. He keeps his solos short; the lessons in concision taught to him in the days of 78 recordings stayed with him. Gordon’s re-entrance continues his solo. Here he uses repeated fragments that follow the harmony, with Clarke keeping busier time until they move into a restatement of the melody.

The standard “Body and Soul” starts with an extended intro on piano by Haig, which is joined by tenor. Dexter’s conception here is shaped by Coltrane’s altered harmony and rhythmic approach. Clarke’s drumming is more restless than one usually gets on this tune. Again, I wonder if it should have been mixed a little bit lower in this track and the bass a little higher. Gordon’s solo doesn’t have a strong developmental thread running through it. It seemed episodic to me, as if he was tackling it in 4 bar sections. Haig’s solo features his distinctive style; again, Bud-like, with a slightly lighter touch and shorter phrases. Very pretty. Gordon returns with an embellished version of the melody, leading to what has become a standard-approach on this tune — an extended coda. Gordon’s version does not allude to the famous Coleman Hawkins version; he quotes “Round Midnight,” takes a leisurely, pensive approach, moves into a few Sonny Rollins-like runs, and finishes it up with Dizzy Gillespie’s ending chord sequence in the coda of “I Can’t Get Started.”

“Antabus” is a Gordon original. For what it’s worth, Antabus is the drug administered to alcoholics. If alcohol is drunk with this in your system you become sick. “Antabus” is a minor blues, reminiscent of Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments,” albeit more up tempo. This kind of tune is mother’s milk to Gordon, who sails through his solo, including a quote from “Mr PC,” the Coltrane tune. It’s interesting to hear Haig start phrases that could become quotes, but not follow that trail, as Gordon so often does. Clarke solos here — not too long, nothing too outré, solid, mostly snare, bass drum and cymbals. Dexter comes back with a restatement of the melody, a brief tag and out.

Sonny Rollins’ trope on rhythm changes, “Oleo,” is next. Rhythmically, this Gordon solo could have been played anytime from the late ’40s on, although he does use some harmonic substitutions that were later additions to standard jazz vocabulary. Haig’s solo is similar: rhythmically, this is well-trod territory for him, but he uses newer harmonic devices. A listener can sit back and relax, taking in the band’s voyage through this tune, watching the venerable harmonic landmarks glide by. Clarke’s solo here is stentorian and solid. Gordon comes back with more variations and then the track closes with a sly, teasing tag.

Monk’s ballad “Round Midnight,” played without Gordon, is programmed last. Yes, digital files create a more flexible notion of the concept of an “album,” but it’s odd that the final cut, on a disc in Dexter Gordon’s name, is a ballad in which he doesn’t perform. Haig states the melody here pretty straightforwardly. His improvisation has a bluesy tinge and toys with the dynamics. He uses more flourishes than usual and makes full use of the upper and lower ends of the keyboard. Michelot solos next, and he takes a fairly melodic approach, with a lot of vibrato on held notes. Haig comes back to close out the disc.

Now, on to the Woody Shaw recording.

Shaw’s group includes pianist Mulgrew Miller, bassist Stafford James, and drummer Tony Reedus. “You and the Night and the Music,” the Irving Berlin standard, opens the set. This tune is taken in a dance like tempo — medium up and with a slightly more emotional edge than usual. Shaw’s style draws on a very personal vocabulary — pentatonics, harmonic substitutions, portamenti, fast slurred runs and a distinctive sound. The timbre of Shaw’s trumpet is probably most similar to Freddie Hubbard’s, but he sounds less burnished and more vulnerable. His solo here is sharp and crisp, full of the gestures and stylizations that mark him as a unique stylist. Mulgrew Miller is a very inventive soloist as well; he uses a wide range of keyboard approaches to create a highly varied solo. Stafford James, a fluid and facile bass player, picks up in his solo on the interesting cues that Miller gives in his piano comping. Drummer Reedus trades 8’s with the band and sounds good. I commend the mix on this track, which gives the drummer his due during his solo, but doesn’t intrude. Shaw takes it out with Miller playing an interesting harmony to the trumpeter’s statement of the melody.

Shaw’s “Rahsaan’s Run” is a modal, up tempo tune; it contains an interesting, somewhat complex, head. Its 14 minutes duration offers everyone plenty of opportunities to air out his thoughts. In fact, every track on this set features extended solos. Virtuosity comes sharply into play given the tempo of this tune, and Shaw is not found lacking. His tonguing, especially, is impressive. Miller takes a dramatic approach, and you can hear the McCoy Tyner influence in his approach to comping 4ths and 5ths in his left hand, with a swift right hand roaming in the upper register. Shaw comes back in blazing and the band displays a lot of flexibility when dealing with time. It actually does stop at one point, and Reedus solos on drums. He varies the colors, making use of the lower toms and bass drum, as well as cymbals, moving in and out of grooves, leading the band back to a final statement of the melody and some closing flourishes by Shaw.

Unusual scales and shifting time signatures mark the next song “Eastern Joy Dance” by pianist Miller. I hear some tuning issues on the piano that I hadn’t detected before, but this happens sometimes when the instrument is getting a good workout, as it is here. Miller’s deft solo moves in and out of Tyner mode. Shaw starts out slowly and melodically. He adds some ornamentation as the rhythm section moves into walking sections, then supplies more forceful statements. The time shifts again, but it doesn’t force melodic alterations. Stafford James on bowed bass follows. This is a challenging tempo for a bowed bass solo, especially an adventurous one. I find him drifting off pitch sometimes, but I really like the daring approach he takes. You find this in “free” solos, but seldom in one with pre-determined harmony. The band sends us off with a recapitulation of the melody, but in a slightly more rounded, less frenzied approach than the original statement of the tune.

Miller’s “Pressing the Issue” begins with him soloing in an ambiguous tonality, with a lot of dynamic changes and register shifts, leading the band into a very uptempo modal tune. Shaw blows several choruses of searing solo. There are brief pauses built into the structure, which provide an effective contrast to the tune’s energy — and a respite for the chops. Miller solos and throws some jagged energy into his flow of sixteenth notes. Again, group pauses serve as a needed release from the tension. Miller stays in after his solo to provide structure, while drums and bass roam fairly freely. The performance is tight. Shaw comes back for the melody and a long, fluid tag.

A Shaw original, the medium tempo tune “The Organ Grinder” follows. The trumpeter composed it in tribute to organist Larry Young, a friend and musical mentor. The band vamps to bring in Shaw’s careful melody. There’s more harmonic contrast in this effort than in the others. James on bass solos first; his performance is fluid and lucid. Shaw’s trumpet follows, starting off in a fairly sedate way, building as he goes along, and ending with an upward rip. Piano and bass take the stage briefly, until Miller’s piano steps out. The solo, like Shaw’s, is more thoughtful and less of a burner than some others. There is a distinct Tyner resonance here as well, though with a more scalar and less percussive touch. Shaw comes back to the melody, which contrasts a jaunty with a questioning feel.

Shaw’s “Katrina Ballerina” does have, as one might expect, a dance-like quality. It’s in waltz time, with occasional shifts in meter. There’s a little bit of a Randy Weston feel in this tune. Miller solos and then Shaw on trumpet. The shifting harmony and meter help keep the solos varied. The bass solos confidently, again with interesting comping by Miller. Shaw takes it out, as the melody fades away.

The entry “Diane” by Lew Pollak and Erno Rapee, was written as part of a soundtrack for the 1927 silent film 7th Heaven. It’s a light tune, closer to a selection in the American songbook than most on this set. Solos by Shaw, Miller, and James show their capacity to excel on a tune with more standard changes.

“400 Years Ago Tomorrow” by Walter Davis Jr. proffers an island lilt that is set in contrast to a more standard modal tune feeling. A ‘B’ section extends the initial spirit of the lilt before the performance moves into a modal burn. The rhythm section encourages the flexibility of the soloists; the beat shapes the solos in a way that generates engaging contrasts in style and mood, shifts from finesse to power and back again. Shaw and Miller move through the process easily. Reedus is given some space on drums before the melody comes back, ending the tune.

These are interesting albums to listen to side by side. Modal tunes are prominent in both, as are fast tempos. Both sets include a lot of original tunes. The presence of Haig and Clarke roots the Gordon sides in a slightly older approach, while Shaw’s group stretches out more in solos and, as a whole, is more comfortable with later jazz approaches. As a soloist, Shaw continues the same singular trajectory he had been establishing over the previous decade, while Dexter seems to have added a few tools to a kit that had been generously outfitted decades earlier. In both recordings you hear the shadow of Coltrane; on Shaw’s recording there’s the strong influence of Tyner in Miller’s performances, while Gordon’s playing, especially on soprano, clearly reflects the influence of Trane. Ironically, early in his career Coltrane acknowledged Gordon as an influence. The jazz cycle continually turns round and about.

The disc includes a 12-page booklet that contains an essay by producer and project coordinator Michael Cuscuna, as well as contributions from Gordon’s widow and biographer Maxine Gordon and from Shaw’s son, Woody Shaw III. I did not receive the booklet so I can’t comment on it.

Steve Provizer is a brass player and bandleader who has been blogging about jazz for 15 years and written about the music for many publications.

Tagged: Dexter Gordon, Elemental Music, Espace Cardin 1977, Live in Bremen 1983, Woody Shaw