Theater Review: “Kiss of the Spider Woman” — Captivity Made Memorable

This was the first stage production in a while that had me on my feet at the end, and thinking and feeling about it long afterward.

Kiss of the Spider Woman, Book by Terrence McNally, Music by John Kander, Lyrics by Fred Ebb. Based on the novel by Manuel Puig. Directed & Choreographed by Rachel Bertone. Music Direction by Dan Rodriguez. Staged by the Lyric Stage of Boston at 140 Clarendon Street, 2nd Floor, Boston, MA, through October 7.

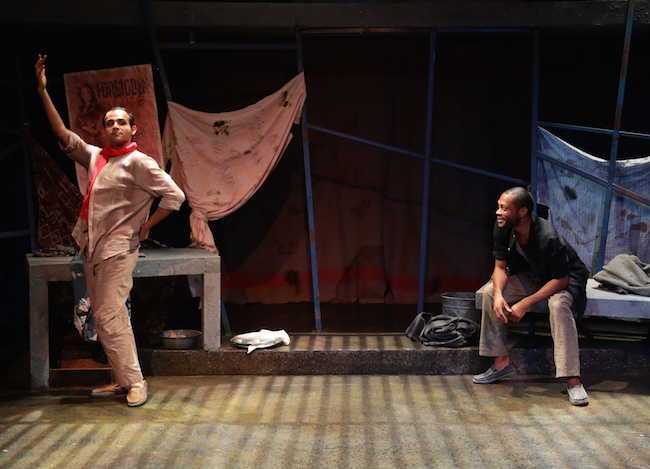

Eddy Cavazos and Taavon Gamble in the Lyric Stage Company of Boston production of “Kiss of the Spider Woman.” Photo: Mark S. Howard.

By Kamela Dolinova

John Kander and Fred Ebb, the great songwriting team behind such immortal hits as Cabaret and Chicago, have never shied from exploring the darker realms of human experience in the American musical format. Kiss of the Spider Woman, the 1993 musical based on the Manuel Puig novel (book by Terence McNally) is no exception, and the effort led to the duo’s third Tony award.

As this reviewer noted in The Arts Fuse about last year’s production of The Scottsboro Boys, Kander and Ebb’s greatest talent was for presenting raw and brutal topics while using highly theatrical conventions to create relief and distance for the audience. As with Cabaret, Spider Woman exploits this format to multilayered effect. The play, with its theme of the imagination serving as a relief from suffering, echoes Cabaret: art, beauty, and yes, love, are sometimes the only escape from imprisonment, torture, and political persecution. Both plays make the audience complicit because we are participating in that escapism on another level. But while Cabaret condemns the decadents of Weimar Germany to their fate through inaction, Spider Woman dramatizes, through its sensitive gay protagonist, heroism in the face of fascism.

The plot revolves around two prisoners in an Argentine jail. Valentin (Taavon Gamble) is a political prisoner, an important prize for an authoritarian regime wishing to crush a growing resistance movement. His cellmate is Molina (Eddy Cavazos), a gay window-dresser serving an eight-year sentence on a trumped-up morals charge. Valentin is the definition of macho and, at first, he rejects Molina out of hand. He draws a real chalk line across the center of the cell, ordering the gay man to stay on his side. But Molina wins Valentin over, helping him escape the torments of confinement by reenacting movies starring his most beloved star, Aurora. The showbiz goddess haunts the proceedings — she performs lavish production numbers that drown out the screams of torture. When the prison warden fails to break Valentin, despite increasingly violent means, he tries to use Molina to draw information on the young revolutionary. But Molina, despite his insistence that he is a coward, makes the ultimate sacrifice to protect Valentin — and, in so doing, at last writes his own inspiring story.

The Lyric Stage Company production, led by the enormously talented young director/choreographer Rachel Bertone, turns what is often presented as a Broadway showstopper into an intimate, emotional ride. Janie Howland’s set evokes both prison bars and a spiderweb; the highly physical ensemble makes great multi-directional use of the ‘steel cage.’ Certain design choices — particularly Aurora’s outfits — take on bold, layered meanings, while the rest of the costumes and lighting are kept largely out of the way of the powerful narrative. The orchestra is one of the tightest and best balanced I’ve heard at the Lyric. But the real engine of this show is the fierce vitality of its lead actors.

Gamble as Valentin is pure masculine power — honor, machismo, and all the toxicity that comes with it. He carries his darker numbers ably, drawing on his resonant yet sharp-edged baritone. The rough intensity of his voice makes the performer’s tender moments all the more heart-piercing. Gamble’s wiry physicality brings a stomach-churning immediacy to the visceral scenes involving torture and privation. His softening, first in scenes with his absent girlfriend Marta, then toward Molina, is an adroit study in reluctant vulnerability.

But the real standout is Cavazos as Molina, who from his first movements in the show grabs the audience and won’t let us go. The character, who could easily be treated as an amalgamation of gay stereotypes becomes, in Cavazos’ hands, a richly-imagined, complex, heartrendingly good man trapped in an impossible time and place. Using his body and voice, brilliantly discovering nuances, he treats Molina with the deepest respect, beauty, and compassion. Not one gesture seems out of place in his portrayal. So it is no surprise when the line Valentin has drawn on the floor is erased, not just by the dancing feet in the blockbuster numbers that Molina invokes, but by the sheer love and bravery Molina shows for Valentin’s sake. The relationship between the two men has the tautness and fragility of a spider web.

Lance-Patrick Strickland, Lisa Yuen, Eddy Cavazos, Taavon Gamble in the Lyric Stage Company of Boston production of “Kiss of the Spider Woman.” Photo: Mark S. Howard.

Supporting this two-handed tour-de-force is a splendid ensemble of male singers and dancers who break our hearts as the doomed fellow prisoners. Trapped in the web of the set, of their prison, of toxic masculinity, they pulse and flex and pace and spin the narrative ceaselessly along. Johanna Carlisle-Zepeda deserves a mention as well. Her grounded presence — and comforting mezzo — brings touching dimension to the character of Molina’s mother.

The surprising weak link in this engaging production is the title character — Aurora, or the Spider Woman. Lisa Yuen is lovely, elegant, and boasts a fine singing voice, but she seems slightly miscast. She executes the choreography ably, but it is clear she is not completely comfortable as a dancer. Bertone wisely flanks Yuen with the same three excellent lead dancers in most of the big numbers; their alternating muscularity and sensitivity heats up the room while physically articulating the play’s themes. The dancers do much to conceal Yuen’s lack of presence. Not everyone can be Chita Rivera, who originated the role on Broadway. But Aurora must always command the stage; the Spider Woman persona is meant (as dreamed up by Molina) to fill us with spine-tingling fear and sexual longing. Yuen is wonderful in the role’s smaller moments, when she is called on to comfort, counsel, or kid. And she can also be extremely funny, suggesting that she is more comedian than grand chanteuse. In the big production numbers, she is simply not captivating enough.

This quibble carries less importance in this production, however, given the ways Bertone has changed the staging of the show’s ending. With permission from the estate, she has re-centered the story’s denouement on the relationship between Valentin and Molina, which the production has spent the past 2.5 hours building. The result is not only thrilling, but emotionally overwhelming.

All told, this was the first stage production in a while that had me on my feet at the end, and thinking and feeling about it long afterward. Years ahead of their time, Kander and Ebb — and of course, Puig — created a story that challenges what it means to “be a man,” as Valentin implores Molina. Instead, Kiss of the Spider Woman asks every one of us what it means to be human.

Kamela Dolinova is a writer, actor, director, healer, and person with too many jobs. She loves the community and little theatre scenes in Boston, and has recently enjoyed working with Flat Earth Theatre, Theatre@First, and Maiden Phoenix Theatre Company. She also blogs at Power In Your Hands and at Medium.