Dance Review: Boston Ballet — Time After Time

Jerome Robbins makes me think about how nonverbal characters can inhabit their times.

Genius at Play, Boston Ballet tribute to Jerome Robbins (1918-1998). Boston Opera House, Boston, MA, through September 16.

Boston Ballet in Jerome Robbin’s “Interplay.” Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

By Marcia B. Siegel

Boston Ballet opened the fall season with a celebration of Jerome Robbins’s 100th birthday. The program began with the overture to Candide by another centenarian, Leonard Bernstein. Robbins didn’t have anything to do with Bernstein’s 1956 operetta, but the two collaborated on what would be the first of several ballets and musical shows, Fancy Free. After the Candide opener, conducted by principal guest conductor Beatrice Jona Affron, the company danced Interplay (Morton Gould, 1945), Fancy Free (1944), and the eponymous Glass Pieces (1983). Beginning in the World War II era, the ballets ended in the post-minimalist ’80s, with Candide casting acerbic glances at mid-century.

Jerome Robbins makes me think about how nonverbal characters can inhabit their times. In Interplay the eight dancers are adolescents, flirting and playing team games. In Fancy Free the sailors and girls behave as if New York City is freer and more relaxed than today’s metropolis. The crowds of Glass Pieces are dehumanized and carefully disciplined, like someone’s idea of postmodern dancers. It’s probably just an accident of programming that this seems like some kind of evolution. Robbins fabricated other character types over his long career: predatory female bugs (The Cage, 1951), musical highbrows (The Concert, 1956), baroque aristocrats (The Goldberg Variations, 1971), commedia dell’arte clowns (Pulcinella, 1972).

Everyone in Fancy Free — three sailors and three “passers-by” — has a distinct identity. The sailors are tall and cool (Patric Palkens on Thursday night), sensitive and shy (Paul Craig), and short and feisty (Isaac Akiba). The passers-by would have been called girls at the time but now are women: self-possessed (Maria Alvarez), romantic (Kathleen Breen Combes), and luscious (Dawn Atkins). They seemed more knowing, more grown-up than they have in past productions. The sailors looked self-conscious in the macho competitions that drive the wispy plot. Put it down to the political imperatives of our times — the rules of interpretation can allow for some adjustment and updating. But Robbins often did make his females twittery and demure.

I can hardly look at Fancy Free for itself anymore, it’s become so encrusted with its own history. Immediately after its initial success at Ballet Theater, Robbins and Bernstein, with Betty Comden and Adolph Green, greatly expanded the scenario and turned it into a smash-hit Broadway show. On the Town (1944) had a New York story and only one ballet dancer, Sono Osato. Five years later some of the same team turned On the Town into a movie with Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, Jules Munshin, Ann Miller, Betty Garrett, and Vera Ellen. Robbins ceded the choreography to Kelly, who co-directed the movie with Stanley Donen. A few years after the ballet’s debut at Ballet Theater, Robbins moved over to New York City Ballet. Fancy Free migrated there around 1980, understandably absorbing the NYCB’s more classical style.

NYCB’s Jean-Pierre Frohlich staged the current Boston cast. Further blurring the history, Boston Ballet posted an online “trailer” for the “Genius at Play” program with members of the cast riffing on the movie’s famous opening scene, where the three sailors come romping off their ship ready to begin their one-day shore leave in New York.

Interplay is dated, in a good way. The ballet hasn’t had the exceptional popularity and reach of Fancy Free, perhaps because it’s plotless and in effect characterless. Only Robbins’s second ballet, its formal structure shows him beginning to learn how to move groups around. The music, Morton Gould’s “American Concertette,” was certainly a period piece, one of many things written in the ’30s and 40s that blended jazz and popular motifs with classical music.

Interplay begins with the men accumulating in a group (led by Patric Palkens). Then women arrive one by one; their group infiltrates the men’s ensemble. The music boogies; they line up at the edge of the orchestra pit and peer in, trying a few boogie woogie moves and finger snaps. When they’re all tired out and resting, a male soloist (Derek Dunn) shows off and invites his friends to join him. A man and a woman (Seo Hye Han and Patrick Yocum) dance a slow, tentative duet while the others pose in silhouette, softly bouncing up and down to the bluesy orchestra. Finally, Dunn and Palkens choose up sides for a friendly competition about who can do the most tricky steps. The whole thing ends with a fast, showbiz pattern as the men slide between the women’s legs to prop themselves up on their elbows. They all grin at the audience.

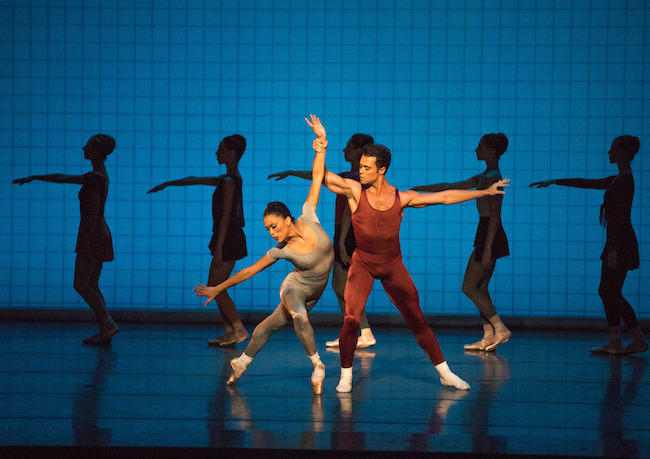

Lia Cirio and Paulo Arrais in Jerome Robbin’s “Glass Pieces.” Photo: Rosalie O’Connor; courtesy of Boston Ballet.

Robbins became a master at cranking up excitement. So did Philip Glass, whose extruded-minimalist In the Upper Room score for Twyla Tharp in 1986 got louder and faster as the dance got more and more crowded and the audience got more excited. For Glass Pieces (1983) Robbins used two sections from the “Glassworks” album and an excerpt from the opera “Akhnaten,” which Robbins was supposed to choreograph, until the death of George Balanchine drew him into his role as an associate ballet master at NYCB. I saw the premiere in New York. I’m not sure it was as big as the Boston production’s 44 dancers, but it was also stunning.

These hordes begin the ballet with crowd behavior — individuals cross the stage very fast, walking heels-first. Some look rigid, some look relaxed, but they’re all across and out before you can keep track of any individual. Successive pairs (Chrystyn Fentroy and Roddy Doble, Rachele Buriassi and Drew Nelson, Maria Baranova and Lawrence Rines) emerge from this mass movement. They’re set off by their costumes, the lighting, and their unpredictable spurts into the air. Later they gradually combine and form an ensemble of their own.

Interplay’s silhouette effect comes back. (Jennifer Tipton’s original lighting design was recreated in Boston by Les Dickert.) Women cross upstage one step at a time in silhouette. Their procession seems endless — too dark to identify any of them or keep track of their changing step pattern. Center stage, Lia Cirio and Paulo Arrais dance a slow pas de deux, folding and extending their limbs, wrapping around each other but seeming to have only an imaginary relationship.

The last movement is a grandiose exposition and organization of the crowd, with the drum-driven orchestra keeping a steady pulse under marathon arpeggios and exclamations in the brasses. As the groups collect and form designs, the relentless music forces them into high gear. I could almost hear the dancers breathing, as their endorphins rose to a sudden full stop.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.