Film Review: At Harvard Film Archive –“The Complete Luchino Visconti”

Luchino Visconti made theatrically tinged movies driven by music, indebted to painting, sculpture, architecture, and literature—he accomplished, dare I say, a fusion of the arts.

The Complete Luchino Visconti or, Luchino Visconti, Architect of Neorealism – at Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, MA, June 1 to July 15.

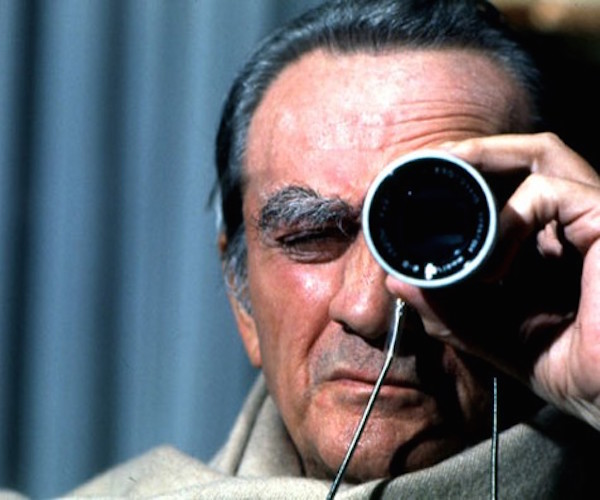

Director Luchino Visconti — aristocrat, Marxist, and (closeted) homosexual. Photo: Taste of Cinema.

By Betsy Sherman

This year’s summer retrospective at the Harvard Film Archive, The Complete Luchino Visconti or, Luchino Visconti, Architect of Neorealism, presents 12 of the Italian master’s 14 features and four of his short films (La Terra Trema and Sandra were shown in May as a prelude to the body of the series). It opens on Friday, June 1 with his masterpiece, The Leopard.

The Milan-born Visconti (1906-1976) is often spoken of with identity tags attached: aristocrat, Marxist, (closeted) homosexual. He’s associated with a grandeur that, in works such as The Leopard, was exhilarating, but that occasionally over-ripened into excess and decadence. The distinctive Visconti style developed during the period in between his second and third films, when he ran a theater company that premiered Italian versions of plays by Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, and Jean Cocteau. Visconti also became a well-known director of operas (he helped launch Maria Callas) and he produced ballets. Visconti stirred this live-event excitement into his cinema, making theatrically tinged movies driven by music, indebted to painting, sculpture, architecture, and literature—he accomplished, dare I say, a fusion of the arts.

It’s architecture that is nodded to in the HFA’s series title, and in Harvard scholar Hugh Mayo’s program essay that posits “a Gothic character to Visconti” in relation to the use of light in the director’s pioneering neorealist films of the 1940s. The use of light is masterful in the largely exterior-shot La Terra Trema (1947), a drama of class struggle filmed in a Sicilian fishing village with a cast of non-actors speaking in their regional dialect. However, in that film is also found Visconti’s natural turn towards the baroque: its aesthetic scheme is dominated by diagonal movement, except for that constant and deceptively stable horizon of the sea.

Clara Calamai and Massimo Girotti in a scene from “Ossessione,” directed by Luchino Visconti.

Visconti had made a harbinger of the postwar neorealist movement with his adaptation of James M. Cain’s pulp tale of adultery and murder, The Postman Always Rings Twice. His Ossessione (1942) depicted doomed carnality between members of the exploited underclass living in Mussolini’s Italy. The characters played by hunky Massimo Girotti and earthy Clara Calamai may be caught in a metaphorical web of fate, but the actors themselves were mired in real dust and sweat courtesy of Visconti’s blunt, naturalistic approach. This frankness resulted in the film’s mutilation by censors horrified at its unattractive portrait of Italian society. Furthermore, the movie wasn’t shown in the U.S. until many years later because Visconti never obtained the rights to the book.

This gritty debut was an unexpected calling card for the man who had been born Count Don Luchino Visconti di Modrone into the leisure class, and who had dabbled in breeding racehorses. Visconti was given the novel by Jean Renoir, to whom he had been introduced by Coco Chanel, and with whom he entered the movie business as assistant (Visconti later called Renoir “a human influence, rather than a professional one”). Renoir’s devotion to France’s leftist Popular Front inspired Visconti into the anti-Fascist cause; he went further than his mentor and became a life-long communist.

Beginning with La Terra Trema, Visconti would often intertwine family stories with their political backdrops. He presented another poor Sicilian family, newly transplanted to Milan, in Rocco and his Brothers (1960), a powerful and tragic drama that has moments of tenderness and extreme brutality. It’s about four brothers, their mother, and a whore (who attempts to reform). The focus is on two of the brothers who try to make their fortune through boxing: the delicately innocent Rocco (Alain Delon), and the macho Simone (Renato Salvatore). Annie Girardot gives an unforgettable performance as Nadia, the woman who becomes involved with each of them.

Visconti’s theater company was a formative experience for actor Marcello Mastroianni, who went on to star in two literary adaptations for the director: White Nights (1957), co-starring Maria Schell and based on a Dostoyevsky story, and a film of Albert Camus’s The Stranger (1967). Another screen great, Anna Magnani, gives one of her trademark comic/tragic performances as a mother trying to get her little girl into the movies at Rome’s Cinecittà studio in Bellissima (1951). Visconti’s delightful final film, the period piece L’Innocente (1976), features Italian stars of the next generation, Giancarlo Giannini and Laura Antonelli, plus the American actress Jennifer O’Neill.

Alida Valli and Farley Granger in a scene from “Senso,” directed by Luchino Visconti.

The director’s first color feature, Senso (1954), is a stunning melodrama, orchestrated to the most minute detail. Martin Scorsese, who gives it an in-depth analysis in his documentary My Voyage to Italy, says “Senso marks the moment where Visconti began working through total artifice as a way to the truth.” Set in 1866 Venice, it reveals tensions in that city under occupation by Austrian soldiers. An unhappily married countess (played by Alida Valli from The Third Man) falls for one of these soldiers (Farley Granger from Strangers on a Train). This movie too could have been called “ossessione,” as we witness the contessa betray not only her marriage but also the cause of Italian independence. Like Ossessione, the film was censored for its release in Italy, with its magnificent battle scene cut (it has since been restored). An abridged English-language version, entitled The Wanton Countess, further stripped out the political context. This version, with dialogue written by Visconti friend Tennessee Williams, will be shown as well in the HFA series (it’s best seen as a complement to, not a substitute for, the full-length Senso).

Senso is propelled by the music of Verdi, and further Visconti titles bear the mark of other great composers. In the director’s The Damned (1971), which, as per the HFA’s notes, “leaves no taboo unbroken” as it chronicles the disintegration of a German family of steel barons during the rise of National Socialism, Wagner is sung at a gay Nazi orgy that’s intercut with a recreation of the “Night of Long Knives.” That movie is the first of Visconti’s featuring the actor Helmut Berger (in it, he gets to impersonate Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel). Berger became Visconti’s lover, and he stars in the director’s folly, the four-hour Ludwig (1973) about the “mad king” of Bavaria (after the shooting of which Visconti suffered a stroke). He also co-stars with Burt Lancaster in the maudlin Conversation Piece (1974).

The touchstone composer in Visconti’s adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1971) was Gustav Mahler. Mann was said to have based the protagonist, Aschenbach, on him, and the film is suffused with 4th movement of Mahler’s 5th Symphony. Visconti changes Aschenbach from a writer to a composer, but the trajectory is the same: the middle-aged man, on vacation in Venice, becomes obsessed with the effortless beauty of a 14-year-old Polish boy staying at the same hotel on the Lido. Details of décor and costume from the early 20th century surely reflect tableaus familiar to the director from his youth. Visconti diminished the importance of words in favor of visual elements and music; consequently, there’s little dialogue, so star Dirk Bogarde draws on his mimetic skills to transform from a cloistered intellectual to a man who opens the door to sensual desire. Of paramount importance is the gaze between the composer and young Tadzio (Bjorn Andresen), which is conveyed by intercutting and the use of a zoom lens. Death in Venice is not the most subtle mixing of Eros and Thanatos, but it has outstanding passages, including the final shot of the boy standing in the ocean bathed in a golden glow, producing a unity of the elements that suggests the divine.

Burt Lancaster and Claudia Cardinale in in a scene from “The Leopard,” directed by Luchino Visconti.

Series opener The Leopard (1963), based on a novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, takes place, like Senso, during the turbulent 1860s. It traces the measures of the House of Salina—Sicilian nobility—to prevent its own extinction. The family is led by the Prince, played by Burt Lancaster.

The film’s remarkable set-pieces include a battle between the Bourbon defense forces and Garibaldi’s redshirts, and the 45-minute-long ball, in which cast members and extras (500 people in all), move among 14 rooms in the palazzo. The ball is in celebration of the engagement of Tancredi, the Prince’s beloved nephew, and Angelica, the daughter of a nouveau-riche landowner. The character of Tancredi, who at first seems an idealist as he fights alongside the redshirts, gradually reveals himself to be a self-centered pragmatist. The Prince, by endorsing Tancredi’s marriage to the healthy, carnal Angelica, is thinking not only of his family’s tired gene pool, but also about its economic survival. As the couple of the future, Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale move through the film like magnificent beasts.

The restored, Italian-language version of The Leopard that will be screened (as opposed to a truncated English-language version released in the U.S. and U.K.) has a marvelous sweep, with some lovely breathing spaces in between the more plot-oriented scenes. It’s during these breathing spaces that Lancaster’s performance achieves astonishing depth. Especially amidst the tumult of the ball, the Prince’s ruminations, and confrontations with the notion of his impending death—represented by a painting by which he seems mesmerized—convey a beautiful mixture of strength and vulnerability. The waltz that the Prince dances with Angelica has been described as “the last dance of a whole social order.” It’s an adrenalin-charged film moment that only the great Visconti could pull off.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Betsy Sherman, Harvard Film Archive, Italian Neorealism