Theater Interview: Adaptor Neil Bartlett on Seeing Your Own Plague in “The Plague”

Albert Camus brings a bracing response to thinking about the worse that is missing in so many of our current dystopias.

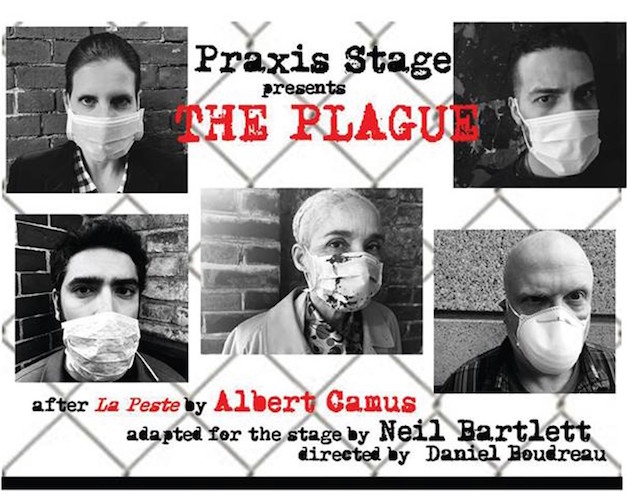

The Plague, the novel by Albert Camus, adapted for the stage by Neil Bartlett. Staged by Praxis Stage at the Dorchester Art Project, 1486 Dorchester Ave, Boston, MA, May 11 through 20 and at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre 949 Commonwealth ave, Boston, MA, May 23 through 27.

By Bill Marx

Yarns of apocalypse are everywhere today, in movies, music, novels, and TV, to the point concerned critics in the New Yorker and elsewhere are wringing their hands about our eager appetite for fictional dystopias, sounding alarms about psychological debilitation and facile escapes from today’s realities. On the stage, however, we have not had many outbreaks of utter darkness, perhaps because aging demographics, along with the lucrative influence of Disney-fied inspiration, dictate a generally pollyann-ish theatrical environment (seen any musicals about flesh-eating zombies lately?).

Thus Neil Bartlett’s 2017 stage adaptation of Albert Camus’s novel about the outbreak of a plague brings with it a refreshing whiff of catastrophe. Five figures from the book, led by the heroic Dr. Rieux, present the beginning and end of an inscrutable disaster. The 1947 novel is set at a specific place Oran (French Algeria) and time (sometime in the ’40s), but the smart approach here is to generalize: this is the dramatization of the slow but steady arrival of a plague in a city that could be anywhere. The script draws on words from the story and there are no slick attempts at ‘updating.” In his preface to the play, Bartlett writes that “the intended effect is that the city in which the action is taking place should be mapped, in the minds of the audience, across the city in which they are actually sitting.”

As for the meaning of the plague, that is left up to the viewer. For Camus, the disease was probably the blight of authoritarianism. Bartlett talks about xenophobia in the interview (via email) below. Who knows what director Daniel Boudreau and the upcoming Praxis Stage production will have in mind? For me, what makes the novel and play resonate today is climate change, with its oh-so gradual spread of death and chaos to all, destruction enhanced by the denial of what is happening and furthered by flawed collective efforts to ward off its horrors. Also welcome: Camus brings a bracing response to thinking about the worse that is missing in so many of our current dystopias. “The misery and greatness of this world: it offers no truths, but only objects for love. Absurdity is king, but love saves us from it.”

Arts Fuse: Asking about your reasons for adapting Camus’ 1947 novel to the stage seems ridiculous. Just last week, Bill Gates warned that a disease that will result in “a global pandemic that could kill up to 30 million people” is coming. And that the world is not ready for a plague “that we should prepare for as if for war.” What contemporary issues did you have in mind when you worked on the stage version of the book?

Neil Bartlett: Well, I don’t know how things are you over there, but here in the UK the real “plague” that we are facing is xenophobia; a drip, drip, drip of hatred and fear of the “other” that is really poisoning British culture. The way people talk about the plague in Camus’ novel is exactly how our politicians and pundits (and voters) are talking about foreigners. And that’s true right across Europe just now as the populist and nationalist right rises and rises. Of course, the reason why Camus’s story is such a classic – why it immediately became a best-seller in conflict-ravaged Europe in 1947, and yet still remains so potent – is that its central metaphor gets re-applied and re-interpreted in every decade. Everyone sees their own plague in the story, because the questions the people in the story face are the ones that everybody faces as their world lurches towards disaster. How can you resist the irresistible ? How can you withstand despair? I can only say that I’ve never felt a story was more timely.

Director/adaptor Neil Bartlett.

AF: What were the challenges posed by adapting Camus’ 1947 novel to the stage?

Bartlett: Ironically, some might argue that, by featuring a number of voices, you improve on the novel, which is told from the heroic Dr Rieux’s point of view. For me the biggest challenge was not to invent anything; I wanted every word that the audience hears in the course of the evening to be by Camus. And that’s what I’ve done — it says Camus on the poster, and Camus is what you get. His writing is astonishing – he knows exactly when and how to hone in on a detail (a rat, a child, an uncompleted sentence) and exactly when to pull out to the bigger picture (love, rage, pain).

AF: What plays or playwright influenced your adaptation? Did any of Camus’ plays or scripts by other absurdist playwrights guide your choices?

Bartlett: My great heroes are Pinter (for economy) and Racine ( or the intensity and the power of the chorus). I also think I had The Wooster Group’s version of The Crucible somewhere in my mind. That said, this is my seventeenth adaptation for the stage (and my tenth from a classic French original) so I also have my own box of tricks.

AF: Critic John Sturrock thought that the “earnest didacticism” of The Plague has not worn well. Why do you disagree?

Bartlett: I don’t see the book as didactic at all – and my adaptation certainly isn’t. I think Camus is an artist of questions, not of answers.

AF: Do you feel that you have mitigated the narrative’s earnestness? There is very little humor in Camus’ book or in your adaptation. Though there death scenes, particularly of a child, that evoke horror.

Bartlett: I wouldn’t say earnestness — though I think maybe some literary critics want to pin on that label, because of their preconceptions about Camus’s politics (which by the way, were fiery and idiosyncratic ). I’d prefer the word passion — and maybe compassion. I don’t think anyone comes to a show called The Plague for a Friday night laugh — but then laughter isn’t the only way of having your heart strengthened after dark.

AF: What should a theater company keep in mind when producing your script? (You directed the premiere 2017 production.) Your staging is minimalist, no longer set in Camus’ specific city and time period (the Algerian coastal town of Oran). How much freedom does a company have in its approach?

Bartlett: When I give permission for a company to direct one of my scripts, then I expect (and encourage) them to do it totally their way. The only thing I suggest with this one is that there should be no literal or graphic presentations of the plague itself. By all means go for the jugular emotionally, but remember that the plague itself is all there in the words. And remember that the main limitation of Camus’s original novel is that all the protagonists are white, and male. In my original London production, they weren’t. I think that matters

AF: Some believe that the Camus’ novel supplies a vision of the absurd — “man’s metaphysical dereliction in the world.” Do you think the story you tell is optimistic?

Bartlett: Whether the show is optimistic or not for me to say, but is for each and very audience member to decide for themselves as the lights come up at the end of the show. Personally I find the bravery of some of the characters very challenging, and very inspiring.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.