Visual Arts: “It’s Alive!” — Undying Terror

A terrifically fun — when not spine-tingling — exhibition of horror and sci-fi memorabilia.

It’s Alive! Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Art from the Kirk Hammett Collection at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, through November 26th.

Collector of memorabilia extraordinaire, Kirk Hammett at the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo: Alison White.

By David Curcio

The first thing you see when you walk into the Peabody Essex Museum’s wildly creative show It’s Alive! Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Art from the Kirk Hammett Collection is a projected picture of Max Schreck’s wraith-like shadow as he ascends a stairway in a scene from F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent masterpiece Nosferatu. Cobwebs are projected on the floor, along with colorful images from the kind of B-classics (Day of the Triffids, et al.) that have inspired this modest-sized exhibition: there are vampires, sinister, glowing eyes, menacing aliens, and other creatures from the deep that gave the era’s buttoned-up zeitgeist the jitters.

The horror film developed along with the advent of film. Anxieties that surfaced in the wake of the First World War (mass graves, poison gas, aerial bombing, tanks) generated fears about the threat represented by Eastern European immigration. A cynical and distrustful American public was afflicted with a fear of the Other: and what could drive the xenophobic message home better than Count Orlav’s arrival by ship, sleeping in a coffin filled with disease-ridden rats?

Attributed to Karoly Grosz, The Mummy, 1932. From the Kirk Hammett Horror and Sci-Fi Memorabilia Collection.

Filmmakers seized on this tension. Despite its status as the black sheep of cinema, horror serves as a bellwether to the country’s political and social climate. Beginning with Murnau’s Symphony of Terror, focus shifted in the 1940s to the monsters and aliens of the atomic age and early space exploration. Body Snatchers hid in plain sight during the Red Scare – there is even a wall-sized photograph of an Ozzie and Harriet-type family watching television inside a fallout shelter. Films denoting the dissolution of the nuclear family (beginning with Rosemary’s Baby), and the changing mythologies and symbolism represented by zombies, the exhibition is a visual timeline of the anxieties of society at large. The trend continued with the torture porn of the Bush years to the xenophobic and feminist commentary of films like Get Out and Martyrs. While It’s Alive does not directly touch on themes beyond the 1980’s (the most recent poster is 1979’s Alien), the wall didactics clarify the themes that drove the genre through the 1970s, before photographic reproduction replaced lithographic renditions of painted (far more effective) imagery.

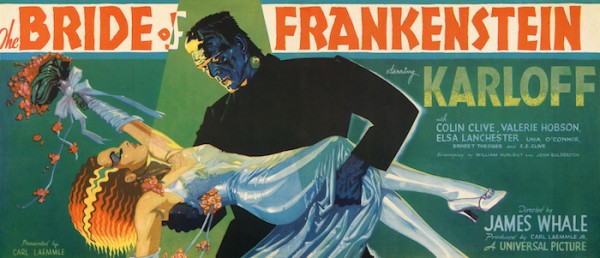

The earliest posters in Kirk Hammett’s collection are from the silent era of the teens and the twenties, including The Phantom of the Opera, Metropolis, and The Cabinet of Dr. Calagari. With the development of sound, Universal Studios dominated the genre, and Hammett is clearly an inveterate devotee of the studio’s giants of grotesquerie, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. Rare posters for several of their films, ranging from Lugosi’s masterpiece Dracula to duds like The Black Cat abound (Editor’s Note: A dud? The Art Deco sets in this Edgar G. Ulmer directed extravaganza are amazing!), including the only extant three-sheet poster for 1931’s Frankenstein. Also present are original costumes (e.g. a suit from one of Karloff’s late films displayed on a mannequin bearing an entirely too believable resemblance to the actor, as well as one of the few masks used in The Creature from the Black Lagoon). Amidst the slew of Lugosi posters is a 1932 oil portrait of the actor by Geza Kende. In a three piece suit and sporting a modest gaze, the eternally type-cast actor is shown with sophistication and dignity.

Original toys in their boxes, including a paint-by-numbers Dracula set (featuring an incomplete and completed version), are a blast, their kitsch mitigating the onslaught of otherwise gruesome (sometimes comically so) posters. One of the most fearsome is a French horizontal one-sheet for Todd Browning’s über-macabre 1932 Freaks (a film featuring deformed circus performers). But behind the dread of encroaching, cartoonish depictions of dwarves, microcephalics (AKA “pinheads”), and other sideshow attractions lies a testimony to the new commercial (now hopelessly outdated) lithography that brilliantly transformed painterly images to luminous reproductions that captured each overlapping stroke with vibrant color.

The Atomic Age introduced films that reflected fears of The Bomb, space travel (who goes? who stays?), and the possibilities of prehistoric giants lying in wait deep below the ocean surface. Posters depicting Godzilla and his ilk dangling trains from their lips while they level cities, bug-eyed aliens firing off ray guns, and tentacles emerging out of the water menacing land and sea are charged with a boisterous energy. These busy, action-packed depictions include multiple scenes from the film being advertised; in contrast to the solitary, glowering, and often symmetrical heads that were used in earlier horror/sci-fi films. The Gothic has been banished by this point — the terrifying is now confined to zooming rockets, blasting lasers, and the incinerator beams wielded by the Martians in George Pal’s War of the Worlds, The posters were so effective that artistic teams were asked to whip up a title and some monsters to fit it. If the studio liked what they saw, it would make make the film. Of course, this often resulted in deep disappointment. The fantastical poster promised a mind-boggling spectacle (The Crawling Eye, for example), but the filmmakers, with little imagination and even less of a budget, couldn’t match what the images promised. The irony is that theaters owners loved the posters, requesting multiple copies in order to rev up an audience that wanted to be scared, but good.

Poster for “The Bride of Frankenstein,” 1935. From the Kirk Hammett Horror and Sci-Fi Memorabilia Collection.

Zombies close out the show. The famous image from 1943’s I Walked with a Zombie (a clever retelling of Jane Eyre) stars the shadow of a reanimated corpse — the sight of it always manages to be chilling, at least for this critic. A large black poster for George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) presents a large skull, the towering text reminding us that “Fear [is] the deadliest emotion clutching at your heart.” Above this picture hangs the iconic poster of its 1978 sequel, Dawn of the Dead: a snarling and malevolent, bald and toothy head rises like a malign sun heralding the end of days. These three films make use of Haitian voodoo mythology, but their political resonances are clear: the walking wounded (returning from WWII and Vietnam), as well as consumerism. How else could a show like this end — but on an apocalyptic note.

A wall festooned with televisions displays looping interviews with Hammett (the lead guitarist for the heavy metal band Metallica). His talking head is surrounded by a collection of guitars adorned with horror film imagery. This may make It’s Alive feel like a vanity exhibition (Hammett’s face is plastered everywhere in the show — we get it, it’s his collection.) Guitar fetish aside, the overall impression is not that Hammett is showing off all the neat stuff that celebrity and wealth can buy; he is simply sharing a treasure trove of beloved cinema memorabilia. What’s more, his perceptions on how the genre has influenced his own artistic process are astute, such as Hammett’s consideration of the difficulties of composing riffs for songs and melodies for silent films.

Some Hammett quotes (projected on raised flooring below the screens and guitars) offer his personal, if not entirely original, views on our need (unconscious and otherwise) to experience fear in a comfortable place, the appeal of being terrified in the safe confines of a theater: “It’s a very, very dark universe when we close our eyes at night… My goal is to take a listener to that darkness…” This idea is not especially illuminating coming from one of the godfathers of Thrash Metal. Thankfully, there’s enough walking dead in this exhibition to legitimately make your skin crawl. To quote Metallica’s Enter Sandman, “Enter night, exit light/take my hand/we’re off to never never land.” That’s exactly where we are in It’s Alive.

David Curcio received his MFA in printmaking from Pratt Institute in 2001. He continues to work in the field of prints as well as embroidery and fiber arts. He has written for bigredandshiny.com, boxingoverbroadway.com and boxing.com. He lives in Watertown, MA.